Kentucky Pride

"A Story of a Horse and the Man Who Loved Her"

Plot

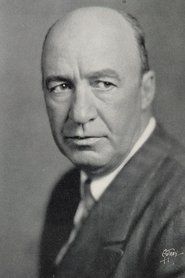

Kentucky Pride tells the heartwarming story of a Kentucky horse breeder named Beaumont (Henry B. Walthall) who raises a magnificent thoroughbred filly named Virginia's Pride. When Beaumont loses his fortune in a high-stakes poker game, he's forced to sell his beloved horse to a wealthy stable owner. The film is largely told from the horse's perspective as she observes the human drama unfolding around her, including Beaumont's struggles to regain his standing and his daughter's (Gertrude Astor) romantic entanglements. Virginia's Pride becomes a champion racehorse, ultimately bringing redemption and restored fortune to her original owner through her racing success. The film culminates in a dramatic race where the horse's loyalty and the breeder's integrity are both vindicated.

About the Production

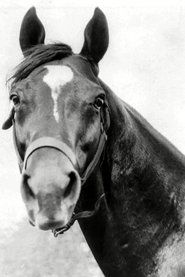

The film featured real thoroughbred racehorses, including the legendary Man o' War, who appeared in several racing sequences. Director John Ford, who had a lifelong love of horses, insisted on authentic racing footage and spent considerable time at Kentucky horse farms researching the subject. The production faced challenges coordinating the racing scenes with actual thoroughbreds, requiring extensive planning and multiple takes to capture the desired footage.

Historical Background

Released in 1925, Kentucky Pride emerged during the golden age of silent cinema and the peak popularity of horse racing in America. The 1920s saw tremendous public interest in thoroughbred racing, with horses like Man o' War becoming national celebrities. The film reflected the era's fascination with the 'Old South' and Kentucky's horse culture, while also embodying the silent film industry's shift toward more sophisticated storytelling techniques. This was also a transitional period for John Ford, who was moving from generic Westerns toward more character-driven dramas that would define his later career.

Why This Film Matters

Kentucky Pride represents an early example of animal-centric storytelling in American cinema, predating more famous films like 'National Velvet' and 'The Black Stallion'. It showcases John Ford's developing visual style and his ability to find emotional depth in seemingly simple stories. The film's use of a horse's narrative perspective was innovative for its time and influenced later animal films. It also serves as an important document of 1920s horse racing culture and Kentucky's thoroughbred industry, preserving on film the legendary Man o' War for posterity.

Making Of

John Ford, who grew up with horses in Maine, brought personal passion to this project. He spent weeks at Kentucky horse farms studying horse behavior and racing culture. The production used innovative techniques to suggest the horse's perspective, including low camera angles and point-of-view shots. The racing sequences required extensive coordination with professional jockeys and horse handlers. Ford insisted on using real thoroughbreds rather than trained movie horses for authenticity. The poker game scenes were filmed with real card players as extras to add realism to the high-stakes atmosphere. The film's emotional core was enhanced by Ford's decision to focus on the relationship between man and animal, a theme he would revisit throughout his career.

Visual Style

The cinematography by George Schneiderman featured innovative low-angle shots to simulate the horse's point of view, a technique unusual for 1925. The racing sequences employed multiple cameras and careful editing to create dynamic action scenes. The film made effective use of natural light in outdoor scenes at Kentucky locations, creating authentic atmosphere. Schneiderman's work demonstrated the growing sophistication of silent film cinematography, with careful attention to composition and movement that enhanced the emotional storytelling.

Innovations

The film pioneered techniques for filming horse races that would influence later sports films. Its use of multiple cameras and strategic placement to capture racing action was advanced for its time. The innovative point-of-view shots suggesting the horse's perspective represented a creative solution to the challenge of telling a story from an animal's viewpoint in silent cinema. The seamless integration of real racehorses, including Man o' War, with fictional narrative was a significant technical accomplishment.

Music

As a silent film, Kentucky Pride would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its theatrical run. The original score was likely composed for theater orchestras and would have featured popular songs of the era along with classical pieces appropriate to the dramatic and racing scenes. Modern restorations have been accompanied by newly composed scores that attempt to capture the spirit of 1920s silent film music while enhancing the emotional impact of key scenes.

Famous Quotes

A horse never forgets a kindness, nor does she forget a wrong

In Kentucky, a man's word is as good as his horse's speed

Fortune comes and goes, but a good horse is forever

The pride of Kentucky isn't in its whiskey, but in its thoroughbreds

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing the birth and early days of Virginia's Pride

- The tense poker game where Beaumont loses his fortune

- The emotional farewell between Beaumont and his horse

- The climactic race sequence with multiple camera angles

- The reunion scene where the horse recognizes her original owner

Did You Know?

- Man o' War, one of the greatest racehorses in history, makes a cameo appearance in the film despite having retired from racing in 1920

- This was one of John Ford's earliest films to explore themes of loyalty and redemption that would become hallmarks of his later work

- The horse's perspective was achieved through innovative camera angles and editing techniques unusual for the time

- Henry B. Walthall, who plays the breeder, was a veteran of D.W. Griffith's films and had previously starred in 'The Birth of a Nation'

- The film was one of the first to use intertitles from the horse's 'point of view', a novel narrative device for silent cinema

- Real Kentucky horse farm owners served as technical advisors to ensure authenticity

- The racing sequences were filmed at Churchill Downs using actual jockeys and race conditions

- Gertrude Astor, who plays the daughter, was one of the few actresses who successfully transitioned from silent to sound films

- The film's original negative was lost in the 1937 Fox vault fire, but copies survived in European archives

- John Ford considered this one of his personal favorites among his silent films due to his love of horses

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film's heartwarming story and authentic racing sequences. The New York Times noted its 'charming simplicity' and 'genuine affection for its subject.' Modern critics have rediscovered the film as an important early work in John Ford's filmography, with particular appreciation for its innovative narrative techniques and beautiful cinematography. The film is now regarded as a minor classic of silent cinema, valued for its technical achievements and emotional sincerity.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by audiences in 1925, particularly those interested in horse racing and animal stories. Its family-friendly content and emotional resonance made it popular with general audiences. Modern audiences who have seen restored versions have responded positively to its timeless themes of loyalty and redemption, though some find the sentimentality typical of the era somewhat dated by contemporary standards.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards were recorded for this film

Film Connections

Influenced By

- D.W. Griffith's narrative techniques

- Contemporary horse racing films

- Victorian animal stories

- American pastoral literary tradition

This Film Influenced

- National Velvet (1944)

- The Black Stallion (1979)

- Seabiscuit (2003)

- Secretariat (2010)

- Ford's later Westerns featuring horses

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered partially lost for decades after the 1937 Fox vault fire destroyed the original negative. However, complete copies were discovered in European archives and have since been preserved by the Museum of Modern Art and the Library of Congress. Restored versions are available, though some quality degradation is evident due to the age of surviving elements.