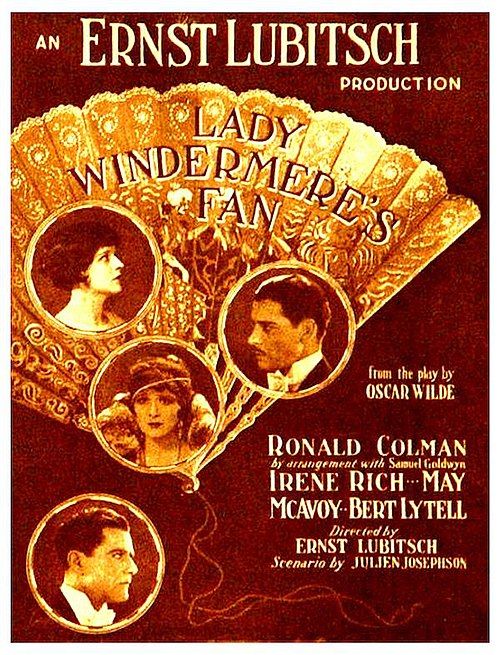

Lady Windermere's Fan

"Oscar Wilde's Brilliant Comedy of Society Scandal Comes to the Screen!"

Plot

In Victorian London, young Lady Windermere discovers her husband Lord Windermere has been secretly giving money to the mysterious Mrs. Erlynne, leading her to believe he's having an affair. When Mrs. Erlynne appears at Lady Windermere's birthday ball, the young woman is horrified and contemplates leaving her husband for the persistent Lord Darlington. In a dramatic turn of events, Mrs. Erlynne reveals she is actually Lady Windermere's long-lost mother, who was disgraced years ago and has now returned to protect her daughter's reputation. After Lady Windermere nearly compromises herself by leaving with Darlington, Mrs. Erlynne sacrifices her own social standing by retrieving her daughter's fan from Darlington's rooms, allowing Lady Windermere to return to her husband unaware of her near-disgrace. The film concludes with Mrs. Erlynne accepting a marriage proposal from Lord Augustus, finding redemption while preserving her daughter's happiness.

About the Production

This was Ernst Lubitsch's first American film for Warner Bros. after being recruited from Germany. The production faced the challenge of adapting Oscar Wilde's famously witty dialogue to silent film form, requiring creative use of intertitles and visual storytelling. Lubitsch insisted on elaborate period-accurate costumes and sets to authentically recreate Victorian London society. The film was shot during the summer of 1925 with a production schedule of approximately 6 weeks, which was considered generous for the time due to its prestige status.

Historical Background

The mid-1920s was a period of transition in Hollywood, as studios moved toward bigger budget prestige productions to compete with radio's growing popularity. Warner Bros., in particular, was trying to establish itself as a major studio capable of producing sophisticated literary adaptations. The film emerged during the Jazz Age, when Victorian morality was being questioned and reexamined, making Wilde's critique of hypocrisy particularly relevant. This was also the peak of the silent era, just before the transition to sound would revolutionize filmmaking. The Roaring Twenties' fascination with the past and European sophistication created an appetite for films like this that offered escapist glamour while still commenting on contemporary moral questions.

Why This Film Matters

Lady Windermere's Fan represents a crucial moment in the transition of European artistic sensibilities to American cinema. Ernst Lubitsch brought his sophisticated European style to Hollywood, influencing generations of filmmakers with what would become known as the 'Lubitsch Touch' - subtle, elegant storytelling that suggested more than it showed. The film helped establish the romantic comedy genre in American cinema and demonstrated that literary adaptations could be both artistically ambitious and commercially successful. It also marked an important step in Warner Bros.' evolution from a minor studio to a major Hollywood player. The film's preservation and rediscovery have made it an important document of silent era filmmaking techniques and a testament to the artistry possible without dialogue.

Making Of

Ernst Lubitsch, already renowned in Europe for his sophisticated comedies, was brought to America by Warner Bros. specifically to elevate their productions with his distinctive directorial style. The adaptation process was particularly challenging as Wilde's play was famous for its brilliant dialogue, which couldn't be fully utilized in a silent film. Lubitsch and his screenwriters solved this by emphasizing visual gags, meaningful glances, and clever intertitles that captured the spirit of Wilde's wit. The casting was crucial - Ronald Colman, though not yet the major star he would become, brought the perfect blend of aristocratic charm and moral ambiguity to Lord Windermere. May McAvoy underwent extensive preparation to portray the innocent but strong-willed Lady Windermere. The production design was meticulous, with art directors creating authentic Victorian London sets that would impress contemporary audiences. Lubitsch was known for his attention to detail, often shooting dozens of takes to get the perfect subtle reaction or gesture that would convey meaning without words.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Charles Van Enger employed sophisticated lighting techniques that created the elegant atmosphere of Victorian London. Van Enger used soft focus and backlighting to create a dreamlike quality in the ballroom scenes, while using more dramatic lighting for the confrontational moments. The camera movement was relatively static, as was typical of the era, but the composition was carefully planned to convey social relationships and power dynamics. The film made effective use of close-ups to capture the subtle emotions that would normally be conveyed through dialogue. The black and white photography was particularly effective in creating the contrast between the respectable surface of society and the darker undercurrents beneath.

Innovations

The film was notable for its innovative use of intertitles that didn't merely convey dialogue but added to the comedy with their own wit. The production design featured some of the most elaborate recreations of Victorian London seen in American cinema up to that point. The film also employed early examples of what would become continuity editing techniques, particularly in the tense scenes involving the fan. The makeup and costume departments created authentic period looks that influenced subsequent historical films. The film's success helped establish technical standards for literary adaptations in the silent era.

Music

As a silent film, Lady Windermere's Fan was accompanied by live musical scores in theaters. For its premiere at the Criterion Theatre in New York, Warner Bros. commissioned a special orchestral score that incorporated popular songs of the Victorian era. In theaters equipped with the Vitaphone system, the film was accompanied by recorded music and sound effects. The score emphasized the comedic moments with light, playful motifs while using more dramatic music for the emotional scenes. Some theaters used classical pieces, particularly works by composers like Johann Strauss II, to enhance the Victorian atmosphere.

Famous Quotes

Mrs. Erlynne: 'I can resist everything except temptation.' (intertitle)

Lord Windermere: 'In this world there are only two tragedies. One is not getting what one wants, and the other is getting it.' (intertitle)

Lord Darlington: 'Life is far too important a thing ever to talk seriously about.' (intertitle)

Duchess of Berwick: 'I don't think I can allow this sort of thing in my house!' (intertitle)

Lady Windermere: 'I am glad to say I have a very strong aversion to anything that is low.' (intertitle)

Memorable Scenes

- The birthday ball scene where Mrs. Erlynne makes her dramatic entrance, causing a stir among the society guests and leading to Lady Windermere's confrontation with her husband

- The tense moment when Mrs. Erlynne discovers her daughter's fan in Lord Darlington's rooms and must decide whether to sacrifice herself to save Lady Windermere's reputation

- The opening sequence showing the elaborate fan that gives the film its title, establishing the visual motif that recurs throughout the story

Did You Know?

- This was the first film adaptation of Oscar Wilde's 1892 play 'Lady Windermere's Fan'

- The film was considered lost for decades before being rediscovered in the 1970s

- Ernst Lubitsch was paid $25,000 for directing, making him one of the highest-paid directors in Hollywood at the time

- Ronald Colman was initially reluctant to take the role of Lord Windermere, preferring more action-oriented roles

- The film showcases what became known as the 'Lubitsch Touch' - sophisticated visual storytelling and subtle comedy

- May McAvoy beat out several other prominent actresses for the lead role of Lady Windermere

- The film's intertitles were written with particular wit to compensate for the lack of Wilde's dialogue

- This was one of the first Warner Bros. films to use the Vitaphone sound-on-disc system for musical accompaniment in some theaters

- The elaborate fan used in the title sequence was specially designed and became a promotional item for the film

- Bert Lytell, who played Lord Darlington, was actually a bigger star than Colman at the time of filming

- The film's success led to Warner Bros. producing more literary adaptations, including other Wilde works

- Oscar Wilde's son Vyvyan Holland reportedly approved of the adaptation

- The ballroom scene featured over 300 extras in authentic Victorian costumes

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film for its sophisticated direction and excellent performances. The New York Times called it 'a triumph of cinematic art' and particularly lauded Lubitsch's ability to translate Wilde's wit to the silent medium. Variety noted that 'the picture proves that good dialogue is not essential when you have good direction.' Modern critics have reevaluated the film as a masterpiece of silent comedy, with the British Film Institute describing it as 'one of the most sophisticated American films of the 1920s.' The film is frequently cited in film studies courses as an example of how visual storytelling can replace dialogue effectively.

What Audiences Thought

The film was a commercial success upon release, particularly with urban audiences who appreciated its sophisticated humor and elegant production values. It played well in major cities like New York and Chicago where audiences were familiar with Wilde's work. The film's themes of marital fidelity and social hypocrisy resonated with 1920s audiences who were questioning traditional values. Word-of-mouth was strong, and the film's run was extended in many theaters. However, in smaller towns and rural areas, it was less successful as the sophisticated humor and themes didn't connect as strongly with those audiences.

Awards & Recognition

- Photoplay Magazine Medal of Honor (1925) - One of the year's best pictures

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Oscar Wilde's original 1892 play

- German expressionist cinema (in lighting techniques)

- European sophisticated comedy traditions

- Drawing-room comedy conventions

This Film Influenced

- The Marriage Circle (1924)

- So This Is Paris (1926)

- The Smiling Lieutenant (1931)

- Trouble in Paradise (1932)

- Ninotchka (1939)

- The Philadelphia Story (1940)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was believed lost for many years but was rediscovered in the 1970s in a private collection. A 35mm print was found and preserved by the Museum of Modern Art. The film has since been restored by the UCLA Film and Television Archive with funding from the National Film Preservation Foundation. The restored version was released on DVD by Warner Home Video in 2008 as part of their Archive Collection. While not complete, the restored version contains all major scenes and is considered remarkably intact for a film of its age.