Lights of New York

"The First All-Talking Picture! A Thrilling Drama of New York's Underworld!"

Plot

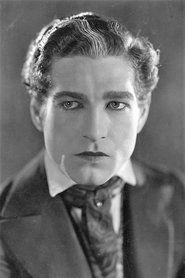

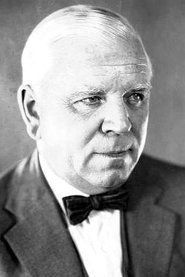

Young Eddie Morgan (Cullen Landis) arrives in New York City with dreams of making it big, but instead falls in with the wrong crowd when he's convinced by a slick-talking gangster named Hawk Miller (Wheeler Oakman) to front a speakeasy operation. Unbeknownst to Eddie, Hawk plans to use him as a fall guy in a complex scheme that involves illegal alcohol distribution and corruption. When a police officer gets too close to uncovering their operation, Hawk murders him and meticulously plants evidence to frame the innocent Eddie for the crime. The story follows Eddie's desperate attempts to prove his innocence while navigating the dangerous criminal underworld of Prohibition-era New York. With the help of his girlfriend Kitty (Helene Costello) and her mother (Mary Carr), Eddie must find a way to expose the real killers before he faces the electric chair for a crime he didn't commit. The film culminates in a dramatic courtroom sequence where the truth finally emerges, bringing the criminal enterprise to justice.

About the Production

Filmed in just 7 days with a budget of only $23,000, this was essentially a B-movie rushed into production to capitalize on the success of 'The Jazz Singer.' The film was shot on a single set with primitive sound recording equipment that required actors to stand still near hidden microphones. Director Bryan Foy, known as 'The Keeper of the B's,' was tasked with creating the first all-talking feature quickly and cheaply. The production faced numerous technical challenges including sound bleed, microphone limitations, and actors' difficulties adapting to performing with dialogue. Despite these constraints, the film was completed ahead of schedule and became a surprise box office success due to public curiosity about talking pictures.

Historical Background

The film was produced during a pivotal moment in cinema history - the transition from silent films to 'talkies.' The Jazz Singer (1927) had demonstrated that synchronized sound could be commercially successful, but that film only contained limited dialogue sequences. In 1928, Hollywood was in a state of technological and artistic upheaval as studios scrambled to convert to sound equipment and theaters rushed to install audio systems. The late 1920s also saw the height of Prohibition in America, making stories about speakeasies and gangsters particularly relevant to contemporary audiences. The stock market crash of 1929 was still a year away, and the Roaring Twenties were in full swing, with audiences eager for entertainment that reflected modern urban life. This film emerged at the intersection of these technological and cultural shifts, essentially capturing the birth of modern cinema as we know it today.

Why This Film Matters

As the first all-talking feature film, 'Lights of New York' holds an unparalleled place in cinema history. While not artistically distinguished, its commercial success proved that audiences would embrace fully synchronized dialogue, effectively sounding the death knell for silent cinema. The film demonstrated that talking pictures could be produced quickly and profitably, accelerating Hollywood's complete conversion to sound within just two years. It also helped establish the gangster film as a viable genre for sound cinema, as the urban crime stories lent themselves well to the new medium's emphasis on dialogue and sound effects. The movie's success created a template for B-movie production that would persist for decades, showing that modestly budgeted films could generate significant returns through novelty and accessibility to popular genres.

Making Of

The production of 'Lights of New York' was a frantic race against time and technology. Warner Bros., having scored a surprise hit with 'The Jazz Singer' (1927), wanted to quickly produce the first all-talking feature to capitalize on the public's fascination with sound cinema. Bryan Foy was given a minimal budget of $23,000 and just one week to shoot the entire film. The primitive sound recording equipment of the era required actors to remain nearly stationary, hidden microphones were placed in flower pots and behind furniture, and camera movement was severely limited. The cast, mostly silent film actors, struggled with the new demands of delivering dialogue naturally while maintaining proximity to the microphones. The film was shot primarily on a single set representing a speakeasy, with clever use of lighting and props to create different locations. Despite these limitations, the production team managed to create a coherent narrative that satisfied audiences hungry for the novelty of hearing characters speak throughout an entire feature film.

Visual Style

The cinematography in 'Lights of New York' was severely constrained by the primitive sound recording technology of 1928. The camera had to remain largely stationary to avoid picking up mechanical noise, and lighting had to be carefully arranged to avoid interfering with the microphones hidden throughout the set. Cinematographer Hal Mohr, who would later win two Academy Awards, had to work within these limitations, creating visual interest through composition and lighting rather than movement. The film employs high-key lighting typical of the era, with dramatic shadows used to suggest the criminal underworld setting. Despite these technical constraints, Mohr managed to create effective visual storytelling within the confines of what was essentially a photographed stage play. The visual style reflects the transitional nature of the film - caught between the expressive cinematography of late silent cinema and the more static, theatrical approach of early sound films.

Innovations

The film's primary technical achievement was being the first feature-length movie with all-talking sequences, a milestone that revolutionized the film industry. The production pioneered techniques for recording dialogue that would become standard practice in early sound cinema, including the strategic placement of hidden microphones in props and set pieces. The film demonstrated that dialogue-driven narratives could work in cinema, paving the way for the development of more sophisticated sound recording techniques. The Vitaphone sound-on-disc system, while cumbersome, proved viable for feature-length productions, though it would soon be replaced by sound-on-film technology. The movie also served as a testing ground for actors' transition from silent to sound performance, establishing new acting techniques that would be refined in subsequent talkies. Perhaps most significantly, the film proved that all-talking pictures could be produced quickly and cheaply, accelerating Hollywood's complete conversion to sound technology.

Music

The film's soundtrack represents a crucial milestone in cinema history as the first complete feature-length synchronized sound production. The Vitaphone sound-on-disc system was used, requiring theaters to synchronize 16-inch phonograph records with the film projector. The soundtrack consists entirely of dialogue and minimal sound effects, with no musical score beyond a brief opening theme. Early sound recording technology meant that audio quality was often poor, with noticeable background noise and limited frequency range. The actors' voices sound somewhat thin and distant by modern standards, reflecting the limitations of the carbon microphones used. Despite these technical shortcomings, the soundtrack was revolutionary for its time, proving that audiences would accept and embrace fully spoken dialogue in feature films. The sound design was minimal, focusing primarily on capturing the actors' voices clearly, which was challenging enough given the primitive equipment available.

Famous Quotes

"Get me a copper! I've been framed!" - Eddie Morgan during his desperate attempt to expose the truth

"This ain't no tea party, kid. This is the big time." - Hawk Miller warning Eddie about the criminal underworld

"In this town, you're either on the make or you're on the take." - One of the gangsters explaining New York's corruption

"A man's gotta do what a man's gotta do, even if it means taking the fall." - Eddie expressing his sense of honor

"The lights of New York shine bright, but they cast long shadows." - Opening narration setting the film's tone

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where Eddie first enters the speakeasy, capturing the audience's first experience of sustained dialogue in a feature film

- The murder scene where Hawk kills the police officer, using off-screen sound and shadows to work around technical limitations

- The courtroom finale where Eddie's innocence is proven, featuring some of the most dramatic dialogue exchanges in early sound cinema

- The tense confrontation between Eddie and Hawk in the speakeasy, showcasing early sound dialogue techniques

- The closing scene where Eddie and Kitty walk away free, with the city lights symbolizing both danger and opportunity

Did You Know?

- This was the first 'all-talking' feature film in cinema history, with every scene containing dialogue rather than just musical numbers or isolated sound segments.

- The film was originally intended as a B-picture but became a massive success purely due to its novelty as a complete talkie.

- Director Bryan Foy was nicknamed 'The Keeper of the B's' at Warner Bros. for his expertise in producing low-budget films quickly.

- The film's success convinced Warner Bros. to invest heavily in sound technology, accelerating the death of silent cinema.

- Many theaters were not yet equipped for sound, forcing Warner Bros. to rapidly convert hundreds of screens to accommodate the film.

- The movie was shot in only one week, making it one of the fastest-produced feature films of its era.

- Actor Cullen Landis had previously been a silent film star and had to adapt his acting style for the new medium of sound.

- The film's plot was loosely based on real Prohibition-era crime stories that were common in New York newspapers.

- Despite its historical importance, the film was considered artistically mediocre even by contemporary standards.

- The original negative was thought lost for decades but was discovered in the Warner Bros. archives in the 1970s.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics acknowledged the film's historical significance while generally panning its artistic merits. The New York Times noted that 'while the novelty of hearing characters speak throughout an entire picture is impressive, the story itself is conventional and the acting often stiff.' Variety praised the technical achievement but criticized the 'stagebound' nature of the production, a direct result of early sound recording limitations. Modern critics and film historians view the film primarily as a historical artifact rather than a work of art. In retrospect, it's recognized as a crucial stepping stone in cinema's evolution, with its artistic shortcomings largely forgiven due to the technological constraints of the era. The film is now studied more for its historical importance than its entertainment value, serving as a time capsule of cinema's awkward but inevitable transition to sound.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1928 were fascinated by the novelty of hearing characters speak throughout an entire film, and 'Lights of New York' became a box office sensation purely on this basis. The film grossed over $1 million against its meager $23,000 budget, an extraordinary return that convinced even the most skeptical studio executives that sound was cinema's future. Contemporary audience members reportedly sat in stunned silence during the first dialogue scenes, with many returning for multiple viewings simply to experience the technological marvel. However, as the novelty wore off and more sophisticated talkies emerged, audience interest in the film itself diminished rapidly. Modern audiences viewing the film today often find it quaint and technically primitive, though classic film enthusiasts appreciate its historical context and its role in transforming cinema forever.

Awards & Recognition

- None - The Academy Awards were not established until 1929

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Jazz Singer (1927) - for pioneering synchronized sound

- Broadway crime plays of the 1920s

- New York newspaper crime stories

- German expressionist cinema (for visual style)

- Contemporary gangster literature

This Film Influenced

- The Broadway Melody (1929) - as an early musical talkie

- Little Caesar (1931) - for establishing the gangster genre in sound

- The Public Enemy (1931) - for sound-era crime storytelling

- Scarface (1932) - for urban crime drama in sound

- Numerous early Warner Bros. gangster films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the Warner Bros. archive and has been restored for home video release. While the original nitrate negatives have deteriorated, a complete 35mm copy exists and has been transferred to digital formats. The Vitaphone sound discs have also been preserved and synchronized with the picture elements. The film is occasionally screened at classic film festivals and is available through Warner Bros.' classic film library. Its preservation status is secure due to its historical importance as the first all-talking feature film.