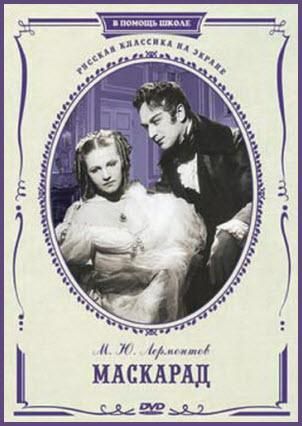

Masquerade

"In a world of masks, truth is the deadliest weapon"

Plot

Set in the decadent aristocratic society of 19th century St. Petersburg, Sergei Gerasimov's 'Masquerade' follows the tragic story of Prince Arbenin, a wealthy but suspicious nobleman, and his beautiful wife Nina. During a lavish masquerade ball, Nina loses her bracelet, which is found by another guest who anonymously gives it to the impetuous young officer Kazarsky, sparking Arbenin's jealousy. As rumors of infidelity spread through the high society gossip mill, Arbenin's possessiveness and pride drive him to seek revenge, ultimately poisoning Nina despite her innocence. The film explores how a single misunderstanding, amplified by the superficial and malicious nature of aristocratic society, leads to irreversible tragedy and the destruction of innocent lives. The story culminates in Arbenin's realization of his terrible mistake, but too late to undo the devastating consequences of his jealousy and the cruel games played by the social elite.

About the Production

The film was completed just before Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. Production faced challenges due to the impending war, with resources being diverted to military needs. The elaborate costume and set design required for the 19th century aristocratic setting represented a significant investment of materials and labor during a time of increasing scarcity. The film's release was severely limited by the outbreak of war, with many prints destroyed during the subsequent conflict.

Historical Background

The film was produced and released in 1941, a pivotal year in Soviet history. Just three months after its release, Nazi Germany launched Operation Barbarossa, invading the Soviet Union and plunging the country into the Great Patriotic War. The timing gives the film particular historical significance as one of the last major cultural productions of the pre-war Soviet era. The film's critique of decadent, corrupt pre-revolutionary Russian society served as powerful propaganda, contrasting the moral bankruptcy of the Tsarist era with the supposed virtue of Soviet society. This message became even more potent after the German invasion, as Soviet propaganda increasingly framed the conflict as a continuation of the revolutionary struggle against oppression. The film's themes of jealousy, betrayal, and the destructive nature of gossip in high society resonated with Soviet audiences as a reminder of what had been overcome by the Revolution. The limited release due to wartime circumstances means that relatively few Soviets saw the film upon its initial release, though it was later revived in the post-war period as a classic of Soviet cinema.

Why This Film Matters

'Masquerade' represents a significant achievement in Soviet cinema's adaptation of classic Russian literature. The film demonstrated how 19th century literary works could be reinterpreted to serve Soviet ideological purposes while maintaining artistic integrity. Its visual style influenced subsequent Soviet historical dramas, particularly in its use of elaborate set design and costume to critique pre-revolutionary society. The film's psychological depth and complex characterizations pushed the boundaries of what was acceptable in Soviet cinema, showing that even within the constraints of socialist realism, filmmakers could explore sophisticated themes of human nature. The performances, particularly Tamara Makarova's portrayal of Nina, became reference points for Soviet actresses playing tragic heroines. The film also contributed to the post-war Soviet cultural narrative that emphasized the moral superiority of Soviet society over the corrupt Tsarist past, a theme that would be revisited in numerous subsequent films. Its survival through World War II, when many cultural artifacts were destroyed, has made it an important historical document of pre-war Soviet filmmaking.

Making Of

The production of 'Masquerade' was a significant undertaking for Mosfilm in 1941, requiring extensive research into 19th century Russian aristocratic life. Costume designers studied historical paintings and documents to create authentic period attire, with some costumes taking weeks to complete. The elaborate masquerade ball scene was particularly challenging to film, requiring complex choreography and lighting to capture the atmosphere of decadent high society. Director Sergei Gerasimov, known for his meticulous attention to detail, demanded multiple takes for key emotional scenes, pushing his actors to deliver nuanced performances that reflected the psychological complexity of Lermontov's characters. The film's score was composed by Aram Khachaturian, who incorporated elements of 19th century Russian dance music while maintaining a modern cinematic sensibility. Production was rushed in its final weeks as the threat of German invasion became increasingly apparent, with the crew working around the clock to complete the film before resources were diverted to the war effort.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Vladimir Rapoport is characterized by its dramatic use of light and shadow to create a sense of psychological tension and moral ambiguity. The film employs a sophisticated visual style that contrasts the glittering surface of aristocratic society with the darkness lurking beneath. The masquerade ball sequence is particularly noteworthy for its complex choreography of camera movement, capturing both the opulence of the setting and the emotional undercurrents among the characters. Rapoport uses deep focus to maintain multiple characters in sharp relief simultaneously, emphasizing how individual actions affect the entire social fabric. The color cinematography, still relatively rare in Soviet films of this era, is used to particular effect in the costume design, with the vibrant colors of the masquerade costumes symbolizing the deceptive nature of appearances. The camera work becomes increasingly claustrophobic as the story progresses, with tighter framing and more restricted movement reflecting Arbenin's growing obsession and Nina's entrapment. The final scenes use stark, almost expressionistic lighting to underscore the tragedy of the resolution.

Innovations

For its time, 'Masquerade' represented a significant technical achievement in Soviet cinema, particularly in its use of color cinematography. The film employed the three-strip Technicolor process, which was still relatively new and expensive in 1941. The elaborate costume and set design required innovative lighting techniques to properly render the colors on film, particularly in the complex masquerade ball sequence. The production also featured advanced sound recording equipment for the period, allowing for clear dialogue reproduction even in scenes with large crowds and orchestral music. The film's special effects, while subtle, included sophisticated matte paintings to create the illusion of 19th century St. Petersburg. The makeup and prosthetics used to age characters and create period appearances were particularly advanced for Soviet cinema of the era. The film's editing techniques, particularly in the rapid cutting during emotional confrontation scenes, pushed the boundaries of conventional Soviet editing styles. These technical achievements were all the more remarkable given that they were accomplished under the pressure of impending war and with increasing resource shortages.

Music

The film's score was composed by Aram Khachaturian, one of Soviet cinema's most distinguished composers. Khachaturian created a rich orchestral score that incorporated elements of 19th century Russian dance music while maintaining his distinctive modern compositional voice. The music for the masquerade ball scene is particularly elaborate, featuring waltzes and mazurkas that evoke the period setting while subtly commenting on the artificiality of the social gathering. Khachaturian uses leitmotifs to represent different characters and themes, with Nina's music characterized by lyrical, melancholic themes that underscore her innocence and tragedy. The score builds in intensity as the plot progresses, with increasingly dissonant elements reflecting the psychological deterioration of the characters and the breakdown of social order. The composer also incorporated traditional Russian folk elements, particularly in scenes that contrast the artificiality of aristocratic life with more authentic emotional expressions. The soundtrack was recorded using the latest technology available in 1941, allowing for a rich, full orchestral sound that enhanced the film's dramatic impact.

Famous Quotes

In this world of masks, everyone wears a face that is not their own - Arbenin

A lost bracelet is a small thing, but in the hands of malice, it becomes a weapon - Nina

We dance and laugh while poison spreads through our veins - Baron

Trust is the first casualty of pride - Prince Zvezdich

In high society, truth is the most dangerous guest at any gathering - Unknown

Memorable Scenes

- The elaborate masquerade ball sequence where Nina loses her bracelet, featuring hundreds of extras in period costumes and complex choreography that captures both the opulence and underlying tension of aristocratic society

- The confrontation scene where Arbenin accuses Nina of infidelity, filmed with increasingly claustrophobic camera work and dramatic lighting that emphasizes the psychological intensity of the moment

- The final poisoning scene, where the camera focuses on Nina's face as she realizes what has happened, creating one of Soviet cinema's most powerful tragic moments

- The opening sequence establishing the decadent atmosphere of 19th century St. Petersburg high society, with sweeping shots of palaces and aristocratic gatherings

Did You Know?

- The film is based on Mikhail Lermontov's 1835 play of the same name, which was controversial in its time for its critique of Russian high society

- Director Sergei Gerasimov also played a small role in the film as one of the party guests

- The film was one of the last major Soviet productions released before the German invasion of the Soviet Union

- Many of the original film prints were destroyed during World War II, making surviving copies particularly rare

- The masquerade ball sequence required over 300 extras in elaborate period costumes

- Tamara Makarova, who played Nina, was married to director Sergei Gerasimov in real life

- The film's release was limited to only a few major cities before war broke out, severely limiting its initial audience

- The bracelet that serves as the central plot device was specially crafted for the film and contained real gems

- This was the first major Soviet adaptation of Lermontov's work on film

- The film's critique of decadent aristocracy was particularly relevant in 1941 as Soviet propaganda emphasized the contrast between corrupt pre-revolutionary society and the new Soviet order

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised 'Masquerade' for its faithful yet modern interpretation of Lermontov's classic play. Reviews in 'Pravda' and 'Izvestia' highlighted the film's visual splendor and the powerful performances of the lead actors. Critics particularly noted how Gerasimov had successfully updated the 19th century story to resonate with 1941 Soviet audiences while maintaining the psychological complexity of the original work. Western critics who saw the film during its limited international release in the late 1940s were impressed by its technical sophistication and the quality of its performances, though some found the ideological elements heavy-handed. Modern film historians consider 'Masquerade' one of the finest Soviet adaptations of classic Russian literature, praising its visual style and psychological depth. The film is now recognized as a masterpiece of the Soviet historical drama genre, with particular appreciation for how it balanced artistic merit with ideological requirements. Recent restorations have allowed contemporary critics to fully appreciate the film's cinematographic achievements, which had been obscured in poor quality prints for decades.

What Audiences Thought

Due to its release just before the German invasion, 'Masquerade' had limited theatrical exposure in 1941, with most Soviet citizens never having the opportunity to see it during its initial run. However, those who did see it in major cities like Moscow and Leningrad reportedly responded positively to its dramatic story and lavish production values. The film was particularly popular among educated Soviet audiences who were familiar with Lermontov's original play and appreciated Gerasimov's interpretation. In the post-war period, when the film was re-released, it found a wider audience and became a beloved classic, with many Soviet viewers citing it as one of their favorite adaptations of Russian literature. The emotional intensity of the story, particularly the tragic fate of Nina, resonated strongly with post-war audiences who had experienced loss and tragedy during the war. The film's critique of decadent aristocratic society also appealed to Soviet audiences' sense of pride in their social system. In modern Russia, the film continues to be shown on television and in retrospectives, where it is appreciated both as a work of cinematic art and as a window into pre-war Soviet culture.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize, Second Class (1941) - For outstanding achievement in Soviet cinema

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Mikhail Lermontov's original 1835 play 'Masquerade'

- 19th century Russian literary tradition of social critique

- Soviet socialist realist aesthetic principles

- Russian theatrical tradition of psychological drama

- European costume drama filmmaking of the 1930s

This Film Influenced

- Later Soviet adaptations of classic Russian literature

- Post-war Soviet historical dramas

- Soviet films critiquing pre-revolutionary society

- Russian television adaptations of literary classics

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been partially preserved, though many original prints were destroyed during World War II. The surviving elements were restored by Gosfilmofond (the Russian State Film Archive) in the 1970s, with a further digital restoration completed in 2005. The restoration process was challenging due to the degradation of the original color negatives, with some scenes requiring extensive color correction. The film is now considered adequately preserved, though some minor elements of the original cinematography may have been lost in the restoration process. The restored version is periodically screened at film festivals and retrospectives of Soviet cinema.