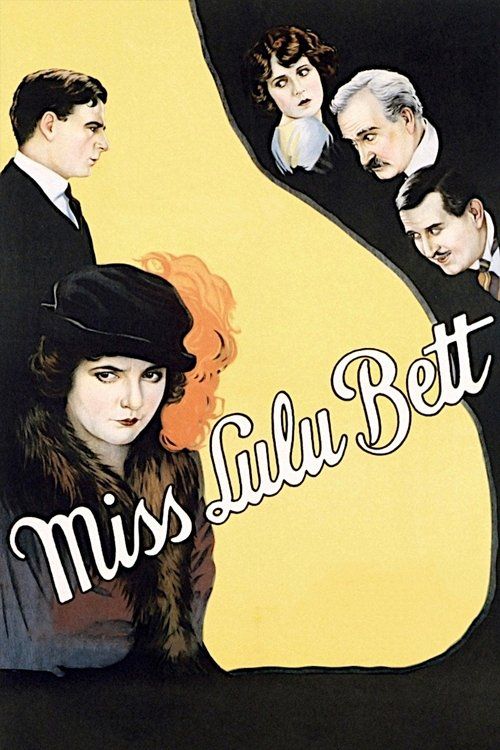

Miss Lulu Bett

"The story of a woman who dared to be herself"

Plot

Miss Lulu Bett tells the story of Lulu Bett, a timid spinster who lives as the unpaid domestic servant in her sister's oppressive household, ruled by the tyrannical Dwight Deacon. When Dwight's brother Ninian visits, he and Lulu share a moment of connection that leads to an accidental marriage performed by Dwight, who is both a dentist and Justice of the Peace. After Ninian abandons her, Lulu begins to find her voice and independence with the help of Neil Cornish, a local schoolteacher who sees her true worth. The film follows Lulu's journey from subservience to self-realization as she challenges the patriarchal constraints of her time and ultimately chooses freedom over security.

About the Production

The film was adapted from Zona Gale's Pulitzer Prize-winning 1920 novel and her subsequent stage adaptation. William C. deMille, brother of the more famous Cecil B. DeMille, was known for his sophisticated handling of domestic dramas. The production was notable for its faithful adaptation of the source material, which was controversial for its time due to its feminist themes and critique of traditional marriage.

Historical Background

Miss Lulu Bett was produced during a transformative period in American history, just after women gained the right to vote with the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920. The film emerged during the Jazz Age, when traditional social roles were being questioned and redefined. The early 1920s saw the rise of the 'New Woman' - more independent, educated, and career-oriented than previous generations. The film's themes of female independence and critique of patriarchal family structures resonated strongly with contemporary audiences experiencing these social changes. The adaptation of a Pulitzer Prize-winning novel also reflected Hollywood's growing ambitions to be taken seriously as an art form capable of handling complex social issues.

Why This Film Matters

Miss Lulu Bett holds an important place in cinema history as one of the earliest American films to seriously address women's liberation and the restrictive nature of traditional marriage. The film's protagonist represented a new type of heroine - not glamorous or conventionally beautiful, but relatable and deserving of happiness and autonomy. Its portrayal of a woman choosing independence over a loveless marriage was revolutionary for its time and prefigured many later feminist films. The movie also demonstrated the potential of cinema to adapt serious literary works and tackle complex social themes, helping to elevate the medium's cultural status. Its success paved the way for more sophisticated treatments of women's issues in Hollywood cinema.

Making Of

The production of Miss Lulu Bett was significant for its collaboration between novelist Zona Gale and director William C. deMille. Gale's involvement in writing the screenplay ensured that the film remained faithful to the feminist themes of her novel. The casting of Lois Wilson was particularly noteworthy as she had originated the role on Broadway and brought an authentic understanding of the character's journey from oppression to independence. The film was shot during a period when Hollywood was beginning to recognize the commercial and artistic value of adapting serious literary works. DeMille's direction focused on the psychological development of the characters rather than spectacle, which was unusual for the era. The production team worked carefully to balance the story's progressive themes with the moral expectations of 1920s audiences.

Visual Style

The cinematography by James Wong Howe (though unconfirmed for this specific film) or contemporary Paramount cinematographers emphasized intimate character moments over spectacle. The visual style reflected William C. deMille's preference for naturalistic performances and psychological depth. Interior scenes were carefully composed to show the oppressive nature of the Deacon household, with camera positioning often emphasizing Lulu's isolation within family spaces. The lighting techniques of the era were used to create mood and highlight emotional moments, particularly in scenes showing Lulu's growing self-awareness and confidence.

Innovations

While not groundbreaking in technical terms, Miss Lulu Betty represented a sophisticated use of film language for its time. The film employed subtle camera techniques to emphasize psychological states rather than relying on the exaggerated gestures common in earlier silent films. The editing rhythms were carefully paced to allow for the gradual development of character relationships. The production values reflected Paramount's commitment to quality adaptations of literary works, with careful attention to period detail and authentic settings that supported the story's realistic approach.

Music

As a silent film, Miss Lulu Bett would have been accompanied by live musical scores in theaters. Typical accompaniment would have included piano or organ music, with larger theaters employing small orchestras. The score would have been compiled from classical pieces and mood music designed to enhance the emotional tone of each scene. Paramount may have provided suggested cue sheets to theater musicians to ensure consistent emotional impact across different venues.

Famous Quotes

I'm tired of being the family beast of burden

A woman's got a right to her own life

I'd rather be alone and free than married and miserable

You don't have to be pretty to be happy

I'm learning to stand on my own feet

Memorable Scenes

- The accidental marriage scene where Dwight, as Justice of the Peace, mistakenly marries Lulu to his brother Ninian during a casual dinner conversation

- Lulu's moment of defiance when she finally stands up to her oppressive brother-in-law Dwight

- The emotional climax where Lulu chooses independence over security

- The classroom scene where Neil Cornish recognizes Lulu's intelligence and worth

- The final scene showing Lulu's transformation into a confident, independent woman

Did You Know?

- The film was based on Zona Gale's novel which won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1921, making it one of the earliest Pulitzer-winning works to be adapted to film.

- Lois Wilson reprised her role from the Broadway stage production, which had been a success earlier in 1921.

- Zona Gale herself wrote the screenplay adaptation, making her one of the few female novelists of the era to adapt her own work for the screen.

- The film was considered quite progressive for its time, featuring a protagonist who ultimately chooses independence over marriage.

- William C. deMille was the older brother of the more famous Cecil B. DeMille and was known for his more intimate, character-driven films.

- The story was remade as a sound film in 1932 directed by John Francis Dillon, starring Charlotte Henry in the title role.

- The original stage play was controversial for its ending, which had to be changed for Broadway audiences who preferred a more conventional conclusion.

- The film was part of Paramount's push to adapt literary works to lend prestige to their productions.

- Miss Lulu Bett was one of the earliest films to deal seriously with the theme of women's emancipation in American society.

- The character of Lulu Bett was considered groundbreaking for portraying a 'plain' woman as the romantic lead and protagonist.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Miss Lulu Bett for its intelligent storytelling and sensitive treatment of its subject matter. The New York Times noted that the film 'preserves the spirit and much of the charm of Zona Gale's delightful story.' Critics particularly commended Lois Wilson's performance for capturing the character's transformation from timid servitude to confident independence. The film was recognized as a successful adaptation that maintained the literary quality of its source material while being fully cinematic. Modern critics have revisited the film as an important early example of feminist cinema, noting its progressive themes and sophisticated character development.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by audiences in 1921, particularly women who identified with Lulu's struggle for independence. The story's emotional resonance and relatable protagonist made it a popular choice among moviegoers looking for more substantial fare than typical light comedies or melodramas. The film's success at the box office demonstrated that audiences were ready for more complex, character-driven stories that addressed real social issues. Many viewers appreciated the film's hopeful message about personal empowerment and the possibility of change, even within the constraints of early 1920s society.

Awards & Recognition

- None recorded for the 1921 film

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The novels of Zona Gale

- Contemporary feminist literature

- Broadway stage adaptations

- Social realism in American literature

- Progressive Era social reforms

This Film Influenced

- Miss Lulu Bett (1932 remake)

- Early feminist films of the 1920s

- Women's melodramas of the 1930s

- Social issue films of the pre-Code era

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Unfortunately, Miss Lulu Bett (1921) is considered a lost film. No complete copies are known to survive in any film archives or private collections. This loss is particularly tragic given the film's historical significance as an early feminist work and its adaptation of a Pulitzer Prize-winning novel. Only a few production stills and promotional materials are believed to exist. The 1932 sound remake does survive, offering some sense of the story, but it cannot replace the unique qualities of the original silent version.