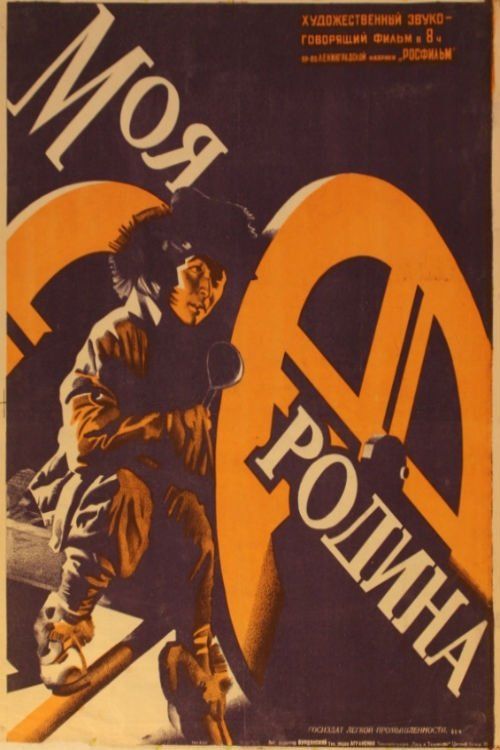

My Motherland

Plot

Set in 1929 during the Sino-Soviet conflict over the Chinese Eastern Railway (CER), the film follows Wang, a Chinese man living in a lodging house who is recruited into a gang preparing to attack Soviet interests. After a sudden attack on a Soviet border village, a Red Army squad recovers and launches a counteroffensive, capturing Wang among other prisoners. During captivity, Wang and another Chinese prisoner attempt to escape, but their journey becomes complicated by internal conflict and ideological differences. Through these experiences, Wang gradually comes to understand the true nature of his enemies and the political realities of the conflict, leading to his political awakening and alignment with Soviet ideals.

About the Production

The film was produced during the early Stalinist era when Soviet cinema was heavily focused on propaganda and historical narratives that supported the official party line. The production would have been subject to strict state censorship and ideological oversight by Glavlit (Main Administration for Literary and Publishing Affairs).

Historical Background

The film was produced in 1933, during the early years of Stalin's rule and the consolidation of Soviet power. It depicts the 1929 Sino-Soviet conflict, which occurred when Chinese warlord Zhang Xueliang attempted to seize control of the Chinese Eastern Railway, a joint Soviet-Chinese venture. The Soviet Union responded with military force, quickly defeating the Chinese forces and reasserting control. This historical event was significant as it demonstrated Soviet military strength in the region and set the stage for Soviet influence in East Asia. The film's creation in 1933 coincided with the rise of Nazi Germany in Europe and increasing Soviet concerns about external threats, making themes of military preparedness and ideological vigilance particularly relevant.

Why This Film Matters

As a Soviet propaganda film, 'My Motherland' served to reinforce official narratives about Soviet foreign policy and military strength. It contributed to the Soviet cultural project of presenting the USSR as a peaceful nation forced to defend itself against foreign aggression. The film's portrayal of Chinese characters and their political awakening reflects the Soviet approach to international relations, emphasizing ideological solidarity over national differences. Like many Soviet films of the period, it would have been used as an educational tool to promote socialist realist values and support the official state narrative. The film is part of the broader Soviet cinematic tradition of using historical events to justify contemporary policies and strengthen ideological commitment.

Making Of

The film was created during a transformative period in Soviet cinema when the industry was consolidating under state control. Director Aleksandr Zarkhi, working within the constraints of the Soviet system, would have had to navigate the complex requirements of socialist realism while attempting to create an engaging narrative. The production would have faced challenges typical of the era, including limited resources, technical constraints, and the need to satisfy ideological requirements from cultural authorities. The casting of Chinese characters likely involved either Chinese actors living in the Soviet Union or Soviet actors in makeup, reflecting the limited international mobility of the time.

Visual Style

The cinematography would have reflected the transition from the experimental techniques of the 1920s to the more conventional style of socialist realism that was becoming dominant in the early 1930s. The visual language would likely have emphasized clear, straightforward storytelling with strong ideological messaging. Battle scenes would have been shot to emphasize Soviet strength and organization, while character close-ups would have been used to convey political awakening and ideological commitment.

Innovations

As a 1933 Soviet production, the film would have utilized the sound technology that was becoming standard in Soviet cinema at the time. The technical aspects would have been constrained by the limitations of Soviet film equipment and resources, but would have represented the industrial capabilities of the Soviet film industry. The battle sequences would have required coordination of extras, military equipment, and special effects within the technical constraints of the era.

Music

The film would have featured a musical score typical of Soviet productions of the era, likely composed by a Soviet composer working within the state system. The music would have emphasized patriotic themes and used leitmotifs to represent different characters and ideological positions. The soundtrack would have included both orchestral passages for dramatic moments and possibly revolutionary songs that were popular in Soviet cinema of the period.

Memorable Scenes

- The attack on the Soviet border village which serves as the catalyst for the Red Army's counteroffensive

- Wang's ideological awakening during his escape journey

- The final confrontation where Wang realizes who his true enemy is

Did You Know?

- The film depicts the real historical conflict of 1929 between Soviet forces and Chinese warlords over control of the Chinese Eastern Railway

- Director Aleksandr Zarkhi was part of the Soviet film establishment and would later direct more prominent films during the Stalin era

- The film was produced during a period when Soviet cinema was transitioning from experimental avant-garde works to more conventional socialist realist narratives

- The character of Wang represents the Soviet propaganda trope of the 'enlightened foreigner' who comes to recognize the superiority of Soviet ideology

- The 1929 Sino-Soviet conflict was a relatively short but significant military confrontation that resulted in Soviet victory and reinforced Soviet control over the CER

- Like many Soviet films of the early 1930s, it likely served both entertainment and educational purposes for Soviet audiences

- The film was part of a broader Soviet effort to justify military actions and present the USSR as defending against foreign aggression

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics would have evaluated the film primarily on its ideological correctness and its effectiveness as propaganda. Reviews in Soviet publications like 'Pravda' and 'Izvestia' would have focused on how well the film served the party's educational mission and whether it successfully portrayed the 'correct' version of historical events. Western critics, if they had access to the film, would likely have viewed it through the lens of Cold War politics, dismissing it as propaganda while perhaps acknowledging its technical merits within the constraints of the Soviet system.

What Audiences Thought

Soviet audiences in 1933 would have received the film as part of their regular cinema-going experience, which was heavily subsidized by the state. The film's message of Soviet military strength and ideological superiority would have resonated with audiences who were exposed to constant propaganda about external threats. The dramatic elements and action sequences would have provided entertainment value while reinforcing the intended political message. Audience reactions would have been shaped by the limited media environment of the time, where films were one of the few sources of information and entertainment.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Soviet socialist realism

- Leninist film theory

- Stalinist cultural policy

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of this 1933 Soviet film is unclear, but like many films from this period, it may be lost, partially preserved, or held in Soviet film archives with limited accessibility. Early Soviet films often suffered from poor preservation conditions and political purges that led to the destruction of 'ideologically incorrect' works.