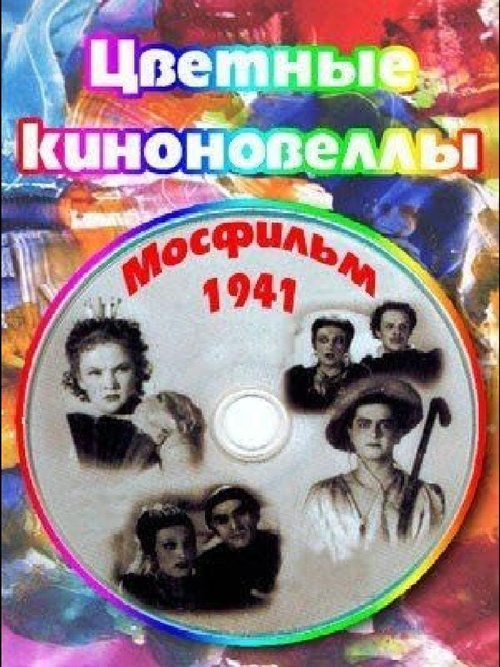

Novelly

Plot

This Soviet anthology film from 1941 presents two distinct fantastical tales. In 'The Swineherd,' based on Hans Christian Andersen's fairy tale, a poor prince disguises himself as a swineherd to win the affection of a spoiled princess who values material possessions over genuine love and creativity. The second segment, 'Heaven and Hell,' adapted from Prosper Mérimée's short story, explores the supernatural consequences of a man's moral choices as he experiences both divine reward and eternal punishment in the afterlife. Both stories serve as allegorical commentaries on human nature, social values, and the consequences of one's actions, presented through the lens of Soviet cinema's unique interpretation of classic European literature.

About the Production

The film was produced by Soyuzdetfilm, a studio specializing in children's and family films. The production took place during a critical period in Soviet history, just before Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. The film's fantasy elements provided a form of escapism for audiences during increasingly tense times. Director Aleksandr Macheret was known for his adaptations of literary works and brought a sophisticated understanding of both Andersen's and Mérimée's original texts to the screen.

Historical Background

The film was produced and released in 1941, a pivotal year in world history and Soviet cinema. The Soviet Union was operating under the Stalinist cultural policy of Socialist Realism, which demanded that art serve ideological purposes while remaining accessible to the masses. Despite these constraints, the film's choice of Western literary sources shows a certain cultural openness. The timing of its release was particularly significant - it premiered just months before Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. This context makes the film's fantasy elements particularly meaningful, as they provided audiences with a form of escapism during increasingly uncertain times. The film industry was already being mobilized for potential war production, and many filmmakers would soon be redirected to produce propaganda and war documentaries. 'Novelly' thus represents one of the last examples of pre-war Soviet fantasy cinema before the industry's complete focus on war effort.

Why This Film Matters

As an anthology film adapting Western European literature for Soviet audiences, 'Novelly' represents an important moment in cultural exchange during a period of relative isolation. The film demonstrates how Soviet cinema engaged with classic literature while reinterpreting it through a Soviet lens. The choice of Andersen's 'The Swineherd' was particularly significant, as fairy tales were considered important tools for moral education in Soviet society. The film's dual structure was innovative for its time and prefigured later anthology films in both Soviet and international cinema. Its preservation of Mérimée's work on screen also contributed to keeping French literature accessible to Soviet audiences. The film serves as a time capsule of Soviet cinematic techniques and artistic values just before the profound changes that World War II would bring to the industry.

Making Of

The production of 'Novelly' took place under challenging circumstances as Europe was already at war and the Soviet Union was preparing for potential conflict. Director Aleksandr Macheret, known for his careful literary adaptations, worked closely with screenwriters to ensure the European stories were appropriately adapted for Soviet audiences while maintaining their essential moral messages. The casting of Yuri Lyubimov, who was just beginning his career, proved prescient as he would later become one of the Soviet Union's most influential theater figures. The film's fantasy elements required innovative special effects for the time, particularly in the 'Heaven and Hell' segment, which used early techniques to create supernatural visions. The production team faced the additional challenge of sourcing appropriate costumes and sets that could evoke both Andersen's fairy tale world and Mérimée's more realistic settings while adhering to Soviet aesthetic principles.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Novelly' employed different visual styles for each segment to match their distinct tones. For 'The Swineherd,' the camera work采用了 softer, more romantic lighting and compositions reminiscent of fairy tale illustrations, creating a dreamlike atmosphere that contrasted with the story's satirical elements. The 'Heaven and Hell' segment used more dramatic lighting and camera angles to convey the supernatural and moral themes, with chiaroscuro effects to emphasize the contrast between good and evil. The film made effective use of studio sets and backdrops, which was standard practice for Soviet productions of the era, while maintaining a visual consistency that unified the two disparate stories.

Innovations

For its time, 'Novelly' demonstrated several notable technical achievements in Soviet cinema. The film's special effects, particularly in the 'Heaven and Hell' segment, used innovative techniques to create supernatural visions and afterlife imagery that were convincing for 1941 audiences. The production successfully maintained visual and narrative consistency across two very different stories, a challenge for anthology films of any era. The costume and set design effectively transported audiences to both Andersen's fairy tale world and Mérimée's more realistic settings while adhering to Soviet production capabilities and aesthetic standards. The film's sound recording and mixing techniques were also advanced for the period, ensuring clear dialogue and effective integration of the musical score.

Music

The musical score for 'Novelly' was composed to complement the contrasting tones of its two segments. For 'The Swineherd,' the music incorporated light, playful motifs reminiscent of classical fairy tale scores, using orchestral arrangements that enhanced the story's satirical and romantic elements. The 'Heaven and Hell' segment featured more dramatic and somber musical themes, employing minor keys and powerful orchestral swells to underscore the moral weight and supernatural aspects of the story. The soundtrack likely drew on both Russian classical traditions and European musical influences, reflecting the international nature of the source material while remaining accessible to Soviet audiences.

Famous Quotes

Material wealth cannot replace true love and artistic integrity

Every action in life has its consequence in the hereafter

The greatest treasures are those that cannot be bought or sold

Memorable Scenes

- The prince's transformation into a swineherd to test the princess's character

- The princess's rejection of the prince's gifts in favor of trivial toys

- The protagonist's journey through the supernatural realms of heaven and hell

- The moral revelation scenes in both stories where characters face the consequences of their choices

Did You Know?

- The film was released in 1941, the same year Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union, making it one of the last pre-war Soviet fantasy films

- Director Aleksandr Macheret was a prominent figure in Soviet cinema who specialized in literary adaptations

- The film was produced by Soyuzdetfilm, which was later renamed Gorky Film Studio and became one of the Soviet Union's most important film studios

- Yuri Lyubimov, who appears in the film, would later become one of the Soviet Union's most renowned theater directors, founding the Taganka Theatre

- The dual-story format was relatively innovative for Soviet cinema of the early 1940s

- Both source stories were from Western European authors, showing Soviet cinema's engagement with international literature despite political tensions

- The film's release coincided with the 100th anniversary of Hans Christian Andersen's death (he died in 1875)

- The Mérimée adaptation was one of the few Soviet films based on French literature during this period

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics appreciated the film's faithful literary adaptations and its moral clarity, though some may have questioned the choice of Western sources during a period of increasing cultural nationalism. The film was generally well-received for its technical merits and the performances of its cast, particularly Yuri Lyubimov. Modern film historians view 'Novelly' as an important example of pre-war Soviet fantasy cinema and a showcase of Aleksandr Macheret's directorial skill in adapting literary works. The film is often cited in studies of Soviet anthology films and the industry's engagement with international literature during the Stalin era.

What Audiences Thought

The film found an appreciative audience among Soviet moviegoers in 1941, particularly families and younger viewers drawn to its fairy tale elements. The fantasy genre provided welcome entertainment during increasingly tense times leading up to the German invasion. The moral lessons embedded in both stories resonated with Soviet values while the familiar literary sources gave the film cultural legitimacy. However, the film's theatrical run was likely cut short by the outbreak of war and the subsequent redirection of the film industry toward war-related content.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Hans Christian Andersen's fairy tales

- Prosper Mérimée's short stories

- Soviet Socialist Realism

- European literary adaptations

- Early Soviet fantasy cinema

This Film Influenced

- Later Soviet anthology films

- Post-war Soviet fairy tale adaptations

- Soviet children's literature adaptations

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

As a Soviet film from 1941, 'Novelly' exists in various archival collections, including the Russian State Film Archive (Gosfilmofond). However, like many films from this period, complete pristine copies may be difficult to find. Some segments or versions may exist only in partial form or in lower-quality transfers. The film's historical significance has likely contributed to preservation efforts, though it may not have received the same level of restoration as more famous Soviet classics from the era.