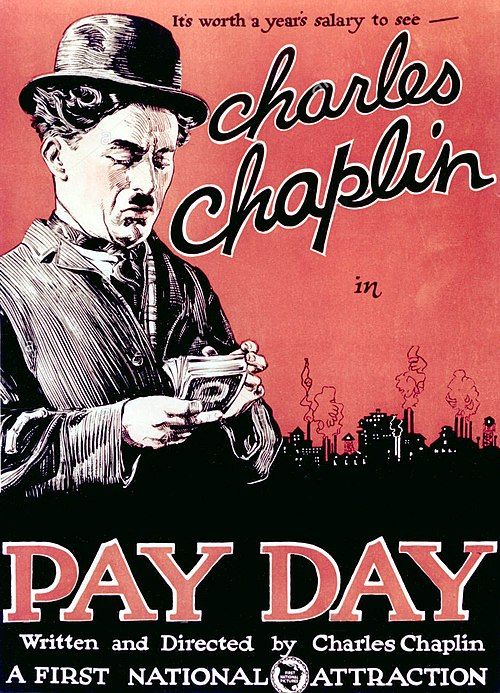

Pay Day

Plot

In this classic Chaplin comedy, The Tramp works as a bricklayer on a construction site, struggling to keep up with the demanding work while maintaining his comical dignity. After enduring a difficult week of labor, he finally receives his hard-earned wages and immediately begins planning a night of celebration with his friends. However, his formidable wife, played by Phyllis Allen, has other plans for his paycheck and insists he come straight home. The film follows Chaplin's increasingly desperate attempts to both enjoy his night out and avoid his wife's wrath, leading to a series of hilarious mishaps including a disastrous attempt to hide money in his hat. The climax features a drunken Chaplin trying to navigate his way home while avoiding both his wife's discovery and the various obstacles that befall him on his journey.

About the Production

Pay Day was Chaplin's 33rd film for First National Pictures and was one of his most successful shorts from this period. The film was shot during Chaplin's most productive era, when he was perfecting the balance between pathos and comedy that would define his later feature films. The construction site scenes were filmed on specially built sets at Chaplin's studio, allowing for precise comic timing and controlled gags. Chaplin was known for his meticulous attention to detail and often shot dozens of takes of each scene to perfect the comedic timing.

Historical Background

Pay Day was released in 1922, during the golden age of silent comedy and at the height of Chaplin's international fame. This period saw the film industry transitioning from short films to feature-length productions, with Chaplin being one of the few comedians who could successfully command audiences for both formats. The early 1920s were also a time of significant social change in America, with the post-World War I economic boom leading to increased leisure time and entertainment consumption. The film's themes of labor, wages, and domestic life resonated with working-class audiences who saw their own struggles reflected in Chaplin's character. Chaplin was at this point one of the most famous and highest-paid people in the world, having just completed his $1 million contract with Mutual Pictures and now working with First National for even greater creative freedom and financial compensation. The film industry was consolidating in Hollywood, and Chaplin's own studio was one of the most sophisticated production facilities of its time.

Why This Film Matters

Pay Day represents a crucial transitional work in Chaplin's career, bridging his earlier slapstick shorts with his more sophisticated feature films. The film demonstrates Chaplin's mastery of the short form while incorporating the deeper character development and social commentary that would define his later masterpieces. The Tramp's struggle between personal freedom and domestic responsibility reflects universal themes that continue to resonate with audiences. The film's depiction of working-class life and the relationship between labor and leisure contributed to Chaplin's reputation as a filmmaker who addressed social issues through comedy. Pay Day influenced countless later comedies that explored the battle between spouses over money and freedom. The film's technical excellence, particularly in its physical comedy and pacing, set new standards for comedy filmmaking. Chaplin's ability to generate laughter while subtly critiquing social norms helped elevate comedy from mere entertainment to a legitimate art form worthy of serious consideration.

Making Of

The production of Pay Day exemplified Chaplin's meticulous approach to comedy filmmaking. He would spend days perfecting individual gags, particularly the bricklaying sequence which required precise timing and physical coordination. Chaplin insisted on doing his own stunts, including the dangerous-looking falls from scaffolding, which caused concern among his crew. The relationship between Chaplin and his regular cast members was well-established by this point, allowing for improvised moments during filming. Mack Swain and Phyllis Allen understood Chaplin's comedic rhythm so well that they could anticipate his movements and enhance the comedy. The film's production coincided with Chaplin's growing interest in feature-length filmmaking, and Pay Day represents the pinnacle of his short-form work before he transitioned to features like 'The Kid' and 'The Gold Rush.' Chaplin's attention to detail extended to the smallest elements, from the specific type of hat used in the money-hiding gag to the authentic construction tools used on set.

Visual Style

The cinematography in Pay Day, credited to Roland Totheroh, demonstrates the sophisticated visual style Chaplin had developed by this period. The film uses deep focus to allow for complex staging of multiple comic actions within the same frame, particularly in the construction site scenes. The camera work is precise but unobtrusive, serving the comedy rather than drawing attention to itself. Totheroh employed innovative tracking shots for the sequence where Chaplin carries his lunch across the construction site, creating visual rhythm that enhances the physical comedy. The film's lighting techniques, particularly in the interior scenes, use chiaroscuro effects to create dramatic contrast between the harsh construction site and the domestic spaces. The cinematography also captures subtle facial expressions that are crucial for conveying emotion in silent film, particularly in the interactions between Chaplin and his wife. The visual composition carefully frames the action to maximize comic effect, with Chaplin often positioned to create ironic juxtapositions with his environment.

Innovations

Pay Day showcases several technical innovations that were advanced for its time. The film's construction site set featured elaborate scaffolding that allowed for dynamic multi-level action, demonstrating sophisticated set design and engineering. Chaplin's use of perspective and forced perspective techniques created illusions that enhanced the comedy, particularly in scenes involving heights and distances. The film employed innovative editing techniques, including match cuts and rhythmic editing that synchronized with the physical comedy. The bricklaying sequence required precise timing between multiple elements and was achieved through carefully choreographed action and strategic camera placement. The film's special effects, while subtle, included matte paintings to extend the construction site and clever camera tricks for the more dangerous-looking stunts. The production also utilized advanced makeup techniques to create the aged appearance of some characters and the various injuries Chaplin's character sustains throughout the film.

Music

As a silent film, Pay Day was originally accompanied by live musical scores performed in theaters, typically consisting of popular songs of the era and classical pieces selected to match the mood of each scene. When Chaplin re-released the film as part of 'The Chaplin Revue' in 1959, he composed an original musical score specifically for Pay Day, reflecting his evolving musical sensibilities. Chaplin's score incorporates leitmotifs for different characters and situations, using playful woodwind passages for the comic moments and more melancholic strings for the scenes of domestic conflict. The 1959 version also included Chaplin's narration, though this was optional for theaters showing the film. Modern restorations typically use Chaplin's 1959 score, which has become the definitive musical accompaniment for the film. The soundtrack enhances the emotional undertones of the comedy while respecting the silent film aesthetic that made the original work so effective.

Famous Quotes

(Intertitle) 'Paid in full - and ready for fun!'

(Intertitle) 'A happy home is where the wife doesn't know what the husband is doing'

(Intertitle) 'The first day of freedom - the last day of money'

(Intertitle) 'A good wife is a blessing - a suspicious wife is a problem'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening bricklaying sequence where Chaplin struggles to keep up with his work while maintaining his dignity, featuring perfectly timed gags with falling bricks and mortar

- The lunch scene where Chaplin attempts to eat his sandwich while avoiding his foreman's gaze, culminating in a classic gag involving a stolen lunch

- The money-hiding sequence where Chaplin desperately tries to conceal his wages from his wife using increasingly absurd methods

- The drunken homecoming where Chaplin navigates a series of obstacles while trying to sneak into his house undetected

- The final confrontation scene where Chaplin's wife discovers his deception, leading to a comic battle of wits and wills

Did You Know?

- This was one of Chaplin's favorite short films he made for First National, often citing it as an example of his perfected short-form comedy.

- The bricklaying sequence required Chaplin to learn actual bricklaying techniques to make the gags more authentic and funnier.

- Mack Swain, who plays Chaplin's coworker 'Big Jim,' was a frequent collaborator with Chaplin, appearing in many of his Mutual and First National films.

- The film's title sequence featured an innovative animated opening with coins falling to form the title, created by Chaplin's brother Sydney.

- Pay Day was re-released in 1959 as part of Chaplin's compilation film 'The Chaplin Revue,' with Chaplin adding his own musical score and narration.

- The hat Chaplin uses to hide his money became one of the most iconic props in the film, demonstrating his genius for turning ordinary objects into comic devices.

- Phyllis Allen, who played Chaplin's wife, was one of the few actresses who could convincingly dominate Chaplin on screen, creating a perfect comedic foil.

- The film was shot in just three weeks, which was relatively fast for Chaplin, who was known for his perfectionism and often took months on shorts.

- A deleted scene reportedly showed Chaplin attempting to bribe a police officer, but it was cut for pacing reasons.

- The construction site set was so elaborate that it was reused for several other films at the Chaplin Studios.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Pay Day as one of Chaplin's finest short comedies, with Variety noting its 'laugh a minute' pace and clever construction. The New York Times called it 'a masterpiece of comic construction' and praised Chaplin's increasingly sophisticated approach to character development. Modern critics have reevaluated the film as a crucial bridge in Chaplin's artistic development, with many considering it among his most perfectly constructed shorts. Film historian David Robinson has written that Pay Day 'represents Chaplin at the height of his powers as a short-form filmmaker, combining brilliant physical comedy with genuine pathos.' The film is frequently cited in academic studies of silent comedy as an exemplary work of the genre, demonstrating Chaplin's mastery of cinematic storytelling without dialogue. Critics have particularly noted the film's perfect pacing and the seamless integration of multiple comic set pieces into a cohesive narrative.

What Audiences Thought

Pay Day was enormously popular with audiences upon its release, playing to packed houses in theaters worldwide. The film's relatable themes of work, money, and marital discord struck a chord with working-class viewers who saw themselves reflected in Chaplin's struggles. Contemporary audience reports described theaters filled with laughter throughout the screening, with particular appreciation for the bricklaying sequence and the drunken homecoming scenes. The film's success contributed to Chaplin's status as the most beloved film star of his era. In the decades since its release, Pay Day has maintained its appeal through revivals and home video releases, with modern audiences still responding to its timeless humor and humanistic approach to comedy. The film's inclusion in 'The Chaplin Revue' in 1959 introduced it to new generations of viewers, and it continues to be featured in film retrospectives and Chaplin festivals around the world.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Chaplin's earlier Mutual shorts like 'The Vagabond' and 'The Cure'

- The tradition of workplace comedy in American theater

- French and Italian comedy films of the 1910s

- Music hall and vaudeville traditions

- The social realist movement in early cinema

This Film Influenced

- Later Chaplin films like 'The Gold Rush' and 'Modern Times'

- Laurel and Hardy shorts of the late 1920s

- Jacques Tati's 'Mr. Hulot's Holiday'

- Modern workplace comedies from 'The Office' to '9 to 5'

- Physical comedies starring actors like Rowan Atkinson and Jim Carrey

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Pay Day is well-preserved with complete copies held in several film archives including the Library of Congress, the British Film Institute, and the Cinémathèque Française. The film has been restored multiple times, most notably for the 1992 Chaplin collection and again for high-definition releases. The original camera negative is believed to be lost, but high-quality prints from the 1920s survive and have been used for restoration. The 1959 re-release version with Chaplin's score is also preserved in excellent condition. The film entered the public domain in the United States in 1948 due to copyright renewal issues, which has contributed to its wide availability but also to the circulation of inferior quality copies. Recent 4K restorations have used the best surviving elements to create definitive versions that showcase the film's original visual quality.