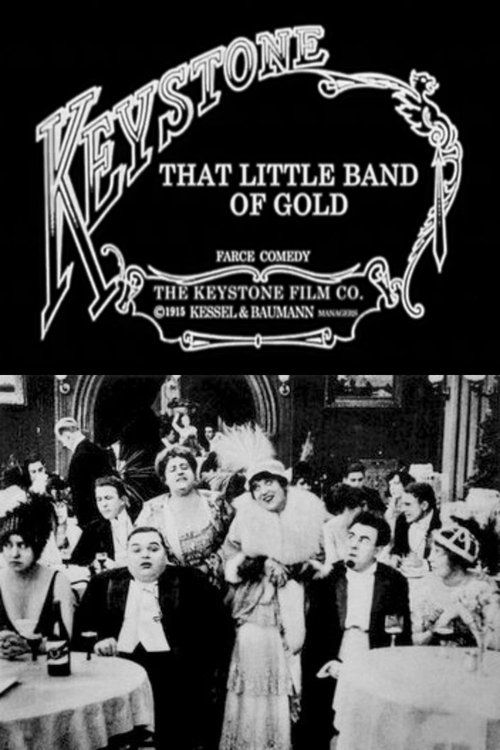

That Little Band Of Gold

Plot

In this silent comedy, a joyous young couple celebrates their engagement and quickly marries, filled with dreams of wedded bliss. However, the husband's commitment to domestic life soon wanes as he begins spending his evenings carousing with friends at bars and clubs, leaving his new wife lonely at home with her mother. The marital discord reaches a climax when the three attend an opera together, where the husband spots one of his drinking buddies in an adjacent theater box and attempts to sneak away to join him. What follows is a series of comedic misunderstandings and slapstick antics as the husband tries to balance his marriage with his desire for freedom. The film culminates in a chaotic resolution that highlights the absurdity of the husband's behavior and the importance of marital fidelity. Through its humor, the film offers a gentle commentary on the challenges of newlywed life and the temptations that can threaten domestic harmony.

About the Production

This film was produced during the peak of Keystone Studios' output, when they were releasing multiple short films per week. The production utilized the classic Keystone formula of fast-paced physical comedy and situational humor. The opera house scenes were likely filmed on studio sets rather than on location, as was common practice for the time. The film was shot in black and white on 35mm film stock typical of the era.

Historical Background

1915 was a pivotal year in both world history and the development of cinema. World War I was raging in Europe, though the United States would not enter until 1917. This global conflict was already affecting the film industry, particularly European production, which helped American studios like Keystone dominate the international market. The film industry itself was undergoing rapid transformation, moving from short one-reel films to longer feature-length productions. Keystone Studios, under Mack Sennett's leadership, was at the forefront of American comedy, pioneering many techniques that would become standard in film comedy. The year 1915 also saw the release of D.W. Griffith's controversial 'The Birth of a Nation,' which demonstrated cinema's potential as both art and propaganda. Meanwhile, the technical aspects of filmmaking were advancing, with better cameras, more sophisticated lighting, and improved film stocks allowing for greater visual sophistication. The social context of 1915 included changing attitudes toward marriage and gender roles, making domestic comedies like this one particularly relevant to contemporary audiences.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents an important example of early American comedy and the Keystone Studios style that would influence generations of filmmakers. As part of the body of work that established the slapstick comedy genre, it helped codify many comedic techniques still used today. The film's focus on domestic themes and marital relationships reflects the growing importance of family life in American culture during the early 20th century. Roscoe Arbuckle's work in films like this helped establish him as one of the most popular comedians of the silent era, second only to Charlie Chaplin in box office appeal during this period. The collaboration between Arbuckle and Mabel Normand was significant as it represented one of the few equal partnerships between male and female stars in early Hollywood. The film also exemplifies how early cinema used humor to explore and comment on contemporary social issues, in this case, the challenges of maintaining marital fidelity in modern urban life. Its preservation and study provide valuable insight into the evolution of American comedy and the cultural values of the 1910s.

Making Of

The production of 'That Little Band of Gold' took place during Keystone Studios' most productive period, when Mack Sennett's factory-like approach to filmmaking was at its peak. The studio operated on an assembly-line system, often shooting multiple films simultaneously on their Edendale lot. Arbuckle, who had risen from being a Keystone player to a director-star, was given considerable creative freedom within the studio's formula. The film's domestic comedy theme was a popular genre at the time, as it allowed for both physical gags and relatable situations. The cast had developed strong chemistry from working together on numerous previous productions, which is evident in their timing and interactions. The opera scenes would have been carefully choreographed to maximize comedic effect while working within the technical limitations of the era's camera equipment and lighting. Like many Keystone productions, the film was likely shot in just a few days, with minimal rehearsal and an emphasis on spontaneous comedic moments.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'That Little Band of Gold' reflects the standard practices of Keystone Studios in 1915. The film was shot in black and white using stationary cameras, with minimal camera movement as was typical of the era. The lighting was primarily natural light supplemented by arc lamps when shooting indoors. The opera scenes would have required more elaborate lighting setups to create the illusion of a theater interior. The visual composition follows the theatrical tradition of the time, with actors positioned to face the camera and important action centered in the frame. The cinematographer would have used multiple camera setups to capture the physical comedy from the most effective angles. The film stock used was likely the standard orthochromatic film of the period, which rendered blues as very dark but was sensitive to greens and yellows. The visual style prioritized clarity of action over artistic composition, ensuring that the physical gags and facial expressions were clearly visible to the audience.

Innovations

While 'That Little Band of Gold' was not particularly innovative technically, it did represent the refined production methods that Keystone had developed by 1915. The studio had perfected the art of rapid production without sacrificing quality, using efficient scheduling and experienced crews. The film demonstrates the effective use of cross-cutting between different locations to build comedic tension, a technique that was still relatively new in cinema. The opera scenes show some sophisticated set design for the period, creating the illusion of a grand theater space within the confines of a studio. The physical comedy sequences required precise timing and coordination between actors and camera, showing the level of technical expertise that had been developed in comedy filmmaking. The film also makes effective use of props and set pieces for comic effect, demonstrating the growing sophistication of production design in comedy. While not groundbreaking, the film represents the polished state of American comedy filmmaking in 1915, with all technical elements working together to serve the humor.

Music

As a silent film, 'That Little Band of Gold' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its theatrical run. The typical accompaniment would have been a pianist in smaller theaters or a small orchestra in larger venues. The music would have been selected from cue sheets provided by the studio, which suggested appropriate musical pieces for different scenes. For the domestic scenes, gentle romantic melodies would have been used, while the carousing scenes would have featured more lively, ragtime-inspired music. The opera scenes would have been accompanied by classical pieces, often parodies of famous operatic themes. The title song, 'That Little Band of Gold,' might have been incorporated into the musical accompaniment, particularly during the wedding scenes. The tempo and style of the music would change to match the on-screen action, accelerating during chase sequences or moments of high comedy. The musical accompaniment was crucial to the silent film experience, providing emotional context and enhancing the comedic timing of the visual gags.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, there are no recorded dialogue quotes, but the intertitles included such lines as: 'After the wedding, things changed...' and 'A night at the opera proves too tempting for the wandering husband.'

Memorable Scenes

- The opera scene where the husband spots his friend and attempts to sneak away, leading to a series of comedic mishaps as he tries to balance his wife's expectations with his desire to join his friends. This scene exemplifies the classic Keystone formula of contrasting high culture with low comedy, using the formal setting of the opera house as a backdrop for slapstick humor.

Did You Know?

- This film was one of over 100 shorts that Roscoe 'Fatty' Arbuckle directed and/or starred in during his prolific Keystone period from 1913-1916.

- Mabel Normand was one of the few women in early Hollywood who had significant creative control, often co-directing her films and having input on scripts.

- Ford Sterling, who appears as one of the carousing friends, was a veteran Keystone comedian known for his exaggerated facial expressions and physical comedy.

- The opera scene was a common setting in early comedies because it provided a natural contrast between high culture and low-brow slapstick humor.

- The film's title refers to a popular song of the era, 'That Little Band of Gold,' which was about wedding rings and marital fidelity.

- Keystone Studios was famous for its 'crash, bang, wallop' style of comedy, and this film exemplifies their approach to domestic situational humor.

- The film was released just as World War I was escalating in Europe, though America had not yet entered the conflict.

- Silent films of this era typically had live musical accompaniment, often consisting of a pianist or small orchestra in the theater.

- The preservation status of this particular film is uncertain, as many Keystone shorts from this period have been lost or exist only in fragmentary form.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of 'That Little Band of Gold' was generally positive, as most trade publications of the era praised Keystone comedies for their energy and humor. The Motion Picture News noted the film's 'clever situations and excellent performances' while Variety highlighted Arbuckle's 'genius for physical comedy.' Modern critics, when able to view the film, recognize it as a solid example of the Keystone formula, though not as groundbreaking as some of the studio's other works. Film historians appreciate the film for its representation of the Arbuckle-Normand collaboration and its typical Keystone production values. The domestic comedy theme was seen as relatable and effective by reviewers of the time, who noted how it balanced slapstick elements with more subtle character-based humor. Some contemporary critics did note that the plot was somewhat formulaic, even by 1915 standards, but acknowledged that the execution and performances elevated the material beyond its simple premise.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1915 generally received 'That Little Band of Gold' enthusiastically, as domestic comedies were popular with theater-goers of the era. The film's relatable theme of marital discord and reconciliation resonated with working-class and middle-class audiences alike. Arbuckle's physical comedy and likable screen persona made him a favorite with moviegoers, and his pairing with Mabel Normand created box office magic. The opera scene, in particular, was noted in audience letters to film magazines as a highlight, with viewers enjoying the contrast between high culture settings and low-brow comedy. The film's short length (16 minutes) made it ideal for the typical program of the era, which usually featured multiple short films along with newsreels and other attractions. While not as memorable as some of Arbuckle's more elaborate productions, the film satisfied audiences' expectations for Keystone-style entertainment and contributed to his growing popularity as a comedy star.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- French comedy of manners

- Music hall traditions

- Vaudeville comedy

- Earlier Keystone shorts

- Domestic melodramas

This Film Influenced

- Later Arbuckle comedies

- Mack Sennett domestic comedies

- Hal Roach's 'Our Gang' domestic episodes

- Early Laurel and Hardy shorts

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of 'That Little Band of Gold' is uncertain. Many Keystone films from this period have been lost due to the unstable nitrate film stock used in the era and the lack of systematic preservation efforts in the 1910s and 1920s. Some sources suggest that fragments or complete copies may exist in film archives such as the Library of Congress or the Museum of Modern Art, but this has not been definitively confirmed. The film's survival would depend on whether it was distributed internationally and preserved in archives, or if it survived in private collections. Given its historical importance as part of Arbuckle's directorial work, preservation efforts would be valuable if original elements still exist.