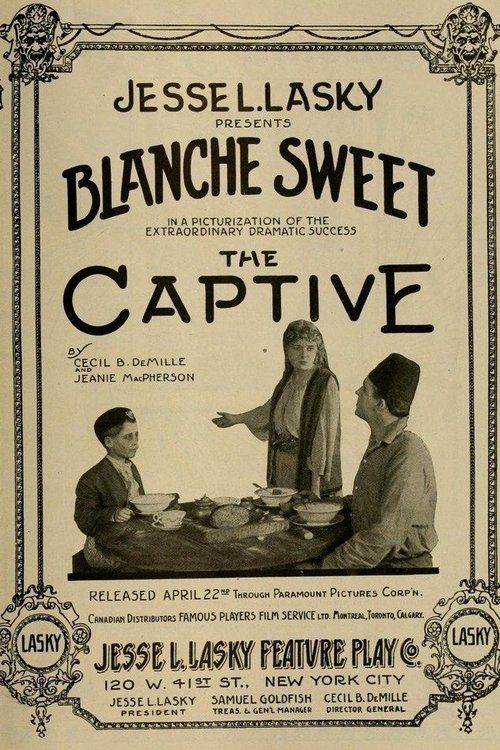

The Captive

"A Love Story Born of War's Cruelty"

Plot

Set against the backdrop of the Balkan Wars, The Captive follows Sonia, a young Montenegrin woman left to manage her family farm and care for her younger brother Milos after her older brother Marko departs for battle. When news arrives of Marko's tragic death in combat, Sonia struggles with the overwhelming responsibilities of farm life and caring for her brother. The situation changes when Mahmud Hassan, a captured Turkish nobleman and prisoner of war, is assigned to help Sonia with her daily tasks. Despite initial hostility and cultural barriers, their relationship gradually transforms from animosity to deep affection as they work together. As the war intensifies around them, Sonia, Mahmud, and young Milos must navigate the dangers of conflict, prejudice, and the uncertainty of their future, ultimately facing impossible choices between love, loyalty, and survival in a war-torn landscape.

About the Production

The Captive was one of Cecil B. DeMille's early feature films, produced during his formative years as a director. The film required extensive set construction to recreate Montenegrin villages and landscapes in California. DeMille was known for his attention to historical detail, and the production team researched Balkan architecture and costumes extensively. The battle sequences were ambitious for 1915, involving hundreds of extras and innovative camera techniques. The film's themes of cross-cultural romance were controversial for the time, particularly given the ongoing tensions in Europe that would soon escalate into World War I.

Historical Background

The Captive was produced during a pivotal moment in world history, released just months before the United States would enter World War I. The Balkan Wars (1912-1913) that form the film's backdrop were fresh in public memory, and the ongoing conflict in Europe made war-themed films particularly relevant. 1915 was also a transformative year for cinema, with feature-length films becoming increasingly common and Hollywood establishing itself as the center of American film production. The Lasky Company, which produced this film, would soon merge with others to form Paramount Pictures. The film's themes of cross-cultural understanding and love transcending national boundaries carried special significance during a time of intense nationalism and growing international tensions. Silent cinema in 1915 was evolving from simple melodramas to more sophisticated narratives, and directors like DeMille were pushing the boundaries of what could be expressed through visual storytelling.

Why This Film Matters

The Captive holds importance as an early example of Hollywood's engagement with international conflicts and cross-cultural romance themes. The film demonstrated Cecil B. DeMille's emerging style of combining intimate human stories with larger historical events, a formula that would define much of his later work. It was among the first American films to present a sympathetic view of a 'enemy' character, challenging the simplistic nationalism common in wartime entertainment. The film's commercial success proved that audiences were ready for more complex narratives that acknowledged the human cost of conflict on all sides. Blanche Sweet's performance helped establish her as one of the era's premier dramatic actresses, capable of conveying deep emotion through the limited means of silent cinema. The film also contributed to the growing acceptance of feature-length films in American cinema, helping move the industry away from the dominance of short subjects. Its treatment of forbidden love across cultural lines would influence numerous later films dealing with similar themes.

Making Of

The production of The Captive reflected Cecil B. DeMille's growing reputation for meticulous attention to detail and his ability to handle complex emotional narratives. DeMille worked closely with his cast to develop the nuanced relationship between Sonia and Mahmud, spending extra rehearsal time on scenes showing their gradual transformation from enemies to lovers. The battle sequences were particularly challenging to film, requiring coordination of hundreds of extras, horses, and early special effects techniques. DeMille pioneered the use of moving cameras during these scenes, creating a sense of immediacy that was innovative for 1915. The film's costume department spent weeks researching and creating authentic Balkan and Turkish attire, with some fabrics imported to ensure accuracy. The set design included full-scale village constructions that could be safely destroyed during battle scenes. Blanche Sweet and House Peters developed good chemistry during filming, though initially Sweet was hesitant about playing a woman who falls in love with the 'enemy.' DeMille's direction emphasized subtle facial expressions and gestures, crucial for conveying emotion in silent cinema.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Captive, handled by Alvin Wyckoff, showcased the increasingly sophisticated techniques being developed in 1915. Wyckoff employed innovative camera movements during the battle sequences, including tracking shots that followed soldiers across the battlefield, creating a sense of immersion that was rare for the period. The film utilized natural lighting extensively, particularly in outdoor scenes, giving the production a realistic quality that distinguished it from the more theatrical-looking films of earlier years. Close-ups were used strategically to emphasize emotional moments, particularly in scenes between Sonia and Mahmud, allowing the actors to convey subtle feelings through facial expressions. The cinematography also made effective use of contrast between the peaceful domestic scenes and the chaotic battle sequences, visually reinforcing the film's central themes. Wyckoff's work demonstrated the growing artistry of film photography in the mid-1910s, moving beyond simple documentation toward expressive visual storytelling.

Innovations

The Captive featured several technical innovations that were advanced for 1915. The film employed sophisticated matte painting techniques to create the illusion of expansive Montenegrin landscapes, combining location footage with painted backgrounds. The battle sequences utilized early forms of multiple camera coverage, allowing DeMille to edit action scenes with greater dynamism than was typical for the period. The production also pioneered the use of detailed miniature models for certain destruction scenes, particularly for the burning village sequences, which were composited with live action footage. The film's special effects team developed new techniques for simulating artillery explosions and gunfire that were more realistic than previous efforts. The costume department created innovative aging and distressing techniques for the military uniforms and civilian clothing to show the wear and tear of war. The film also demonstrated advanced editing techniques for its time, using cross-cutting between the developing romance and the ongoing war to build tension and thematic resonance.

Music

As a silent film, The Captive was accompanied by live musical performances during its theatrical run. The original score was composed by William Furst, one of the prominent film composers of the era, who created a series of musical cues designed to enhance the emotional impact of key scenes. The music incorporated elements of Balkan folk melodies for scenes set in Montenegro, while using more traditional romantic themes for the developing love story. Theater orchestras received detailed cue sheets indicating when to transition between different musical moods, from pastoral themes for farm scenes to dramatic martial music for battle sequences. Some larger theaters augmented the orchestral accompaniment with sound effects, particularly during the war scenes, using techniques like coconut shells for horse hooves and thunder sheets for cannon fire. The musical approach reflected the growing sophistication of film scoring in 1915, moving beyond simple mood music toward more narrative-driven compositions that helped guide audience emotions through the story.

Famous Quotes

Silent film - no recorded dialogue, but intertitle cards included: 'In the midst of war's cruel hatred, love found a way to bloom', 'Even enemies can find common ground in compassion', 'The heart knows no nation when true love calls'

Memorable Scenes

- The first meeting between Sonia and Mahmud, where initial hostility gradually gives way to mutual understanding as they work together on the farm

- The emotional scene where Sonia learns of her brother Marko's death, captured through Blanche Sweet's powerful silent performance

- The climactic battle sequence where Mahmud must choose between escaping to freedom and protecting Sonia and Milos

- The tender moment in the garden where Sonia and Mahmud acknowledge their growing feelings despite the barriers between them

- The final scene as the three characters face an uncertain future together, symbolizing hope amid the devastation of war

Did You Know?

- The Captive was one of the first American films to depict the Balkan Wars, which had occurred only 2-3 years before the film's release

- Blanche Sweet was one of the highest-paid actresses of her time, earning $500 per week for this film

- The film was originally titled 'The War Bride' but was changed to 'The Captive' before release

- Cecil B. DeMille used real Turkish actors and extras for authenticity, unusual for the period

- The film's success helped establish DeMille as a major director capable of handling both intimate dramas and large-scale productions

- House Peters, who played Mahmud Hassan, was actually of German descent, not Turkish, but his exotic appearance made him popular for such roles

- The film was shot in just three weeks, remarkably fast even by 1915 standards

- Some scenes were filmed at the former ranch of director D.W. Griffith, which DeMille's company had recently acquired

- The film's themes of forbidden love across enemy lines were considered quite daring for 1915 audiences

- Gerald Ward, who played young Milos, was actually a child actor who appeared in several DeMille productions

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised The Captive for its ambitious scope and emotional depth. The Moving Picture World called it 'a powerful drama that touches the heart while stimulating the mind,' particularly noting DeMille's skill in handling the sensitive romance between enemies. The New York Dramatic Mirror applauded Blanche Sweet's performance as 'one of her most nuanced and affecting portrayals,' while Variety highlighted the film's impressive battle sequences and authentic production values. Modern critics and film historians recognize The Captive as an important early work in DeMille's filmography, demonstrating his developing mastery of visual storytelling and his ability to balance intimate drama with spectacle. The film is often cited in studies of early American cinema's treatment of war and romance themes, with particular attention paid to its relatively progressive portrayal of cross-cultural relationships for its time.

What Audiences Thought

The Captive was well-received by 1915 audiences, who were drawn to its combination of romance, drama, and spectacular battle scenes. The film's emotional core resonated strongly with viewers, many of whom had family members affected by the ongoing war in Europe. Contemporary newspaper reports noted that audiences were particularly moved by the developing relationship between Sonia and Mahmud, with some theater owners reporting that the film generated more audience discussion than typical productions of the era. The film's success was evident in its extended runs in major cities and strong bookings in smaller markets across the United States. Audience letters published in trade papers praised the film's 'realism' and 'heart-touching story,' with many specifically commending the performances of Sweet and Peters. The film's themes of love transcending war and prejudice struck a chord with audiences weary of the increasing international tensions that would soon engulf America in World War I.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The influence of D.W. Griffith's 'The Birth of a Nation' (1915) in epic storytelling

- European war films depicting the Balkan conflicts

- Contemporary stage plays about war and romance

- Literary works about forbidden love across cultural divides

- Italian historical epics of the early 1910s

This Film Influenced

- Cecil B. DeMille's later war romances like 'The Little American' (1917)

- Other cross-cultural romance films of the silent era

- War films that emphasized human stories over battle spectacle

- Later films dealing with prisoners of war and their relationships with captors

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Captive is considered a partially lost film. Only fragments and portions of the original 5-reel production survive, held in archives including the Library of Congress and the Museum of Modern Art. Some complete scenes exist, but the film in its entirety has not been preserved. The surviving elements were discovered in various archives and private collections in the 1970s and 1980s. Efforts to reconstruct what remains of the film have been undertaken by film preservationists, but significant portions are likely lost forever. The incomplete status makes it difficult for modern audiences to appreciate the film in its original form, though the surviving footage demonstrates the technical and artistic sophistication of DeMille's early work.