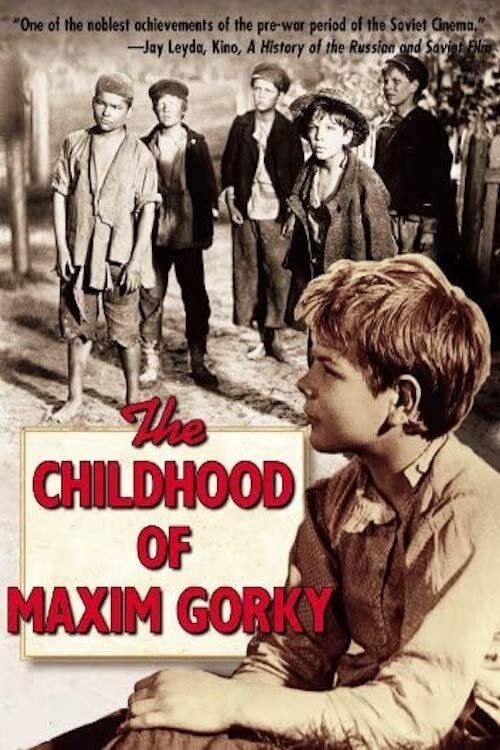

The Childhood of Maxim Gorky

"The story of a boy who became the voice of the Russian people"

Plot

The Childhood of Maxim Gorky portrays the formative years of the future great Russian writer Alexei Maximovich Peshkov, who would become known as Maxim Gorky. After the death of his father, young Maxim is sent to live with his grandparents in a poor household in Nizhny Novgorod. There he endures the harsh discipline and frequent beatings from his martinet grandfather, a cruel dye-works owner who represents the oppressive old order of czarist Russia. In contrast, Maxim finds solace and inspiration from his warm-hearted grandmother, who regales him with folk tales and stories that nurture his imagination and sow the seeds of his future literary career. The film vividly depicts the poverty, social injustice, and human suffering that Maxim witnesses, including his grandfather's business failures, family conflicts, and the brutal realities of life for the Russian underclass. Through these experiences, young Maxim develops a keen social consciousness and begins to understand the power of storytelling as both escape and resistance.

About the Production

The film was part of a trilogy about Gorky's life, with this first installment focusing on his childhood. Director Mark Donskoy faced the challenge of adapting Gorky's autobiographical literary work while adhering to the strict artistic guidelines of socialist realism mandated by Stalin's cultural policy. The production team paid meticulous attention to recreating the authentic atmosphere of 1870s-1880s Russia, from the working-class interiors to the period costumes and props. The casting of young Aleksei Lyarsky as Maxim was particularly praised for capturing the sensitive and observant nature of the future writer.

Historical Background

The film was produced during one of the most turbulent periods in Soviet history - the late 1930s under Stalin's rule. This era saw the height of the Great Purge (1936-1938), during which millions were arrested, executed, or sent to labor camps. Paradoxically, it was also a time of significant investment in Soviet cinema as a propaganda tool. Maxim Gorky, who had died in 1936, had been officially rehabilitated and celebrated as a model Soviet writer who had come from humble origins to support the revolution. The film's emphasis on Gorky's difficult childhood under czarist oppression served to highlight the supposed superiority of the Soviet system. The production had to navigate the strict aesthetic doctrine of socialist realism, which demanded that art be realistic in form and socialist in content. This meant showing the hardships of the past while emphasizing the progress achieved under Soviet rule. The film's release in 1938 came just before the Soviet Union's entry into World War II and during a period of intense cultural censorship and political repression.

Why This Film Matters

The Childhood of Maxim Gorky holds immense cultural significance both as a work of cinema and as a cultural artifact of the Stalin era. It established the template for the Soviet biographical film, balancing personal storytelling with ideological messaging. The film's portrayal of the grandmother as a source of wisdom and folk wisdom resonated deeply with Soviet audiences and became an archetype in Russian culture. It contributed to the cult of personality surrounding Gorky, presenting him as the ideal 'proletarian writer' who rose from the people to serve the revolution. The film's visual language influenced subsequent Soviet cinema, particularly in its use of realistic detail and psychological depth in character development. Internationally, it helped establish Soviet cinema's reputation for serious artistic achievement beyond propaganda, earning praise at the Venice Film Festival. The trilogy as a whole became part of the standard Soviet educational curriculum, with generations of Soviet students watching these films as part of their literary education. The grandmother character, in particular, became a cultural touchstone representing the wisdom and resilience of the Russian people.

Making Of

The production of 'The Childhood of Maxim Gorky' was a significant undertaking for Soviet cinema in the late 1930s. Director Mark Donskoy, who had previously worked mostly in documentary film, brought a realistic approach to the adaptation of Gorky's autobiographical work. The casting process was particularly challenging - Donskoy searched extensively for a child actor who could capture both the vulnerability and perceptiveness of young Gorky, eventually discovering Aleksei Lyarsky in a drama school. The relationship between the young actor and Varvara Massalitinova, who played the grandmother, developed naturally off-screen, contributing to the authentic chemistry seen in the film. The production team conducted extensive research into 19th-century Russian working-class life, consulting historical archives and even speaking to elderly people who had lived through that era. The film's cinematography employed innovative techniques for the time, including low-angle shots to emphasize the child's perspective and natural lighting to enhance the documentary-like realism that Donskoy sought to achieve.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Pyotr Yermolov was groundbreaking for its time in Soviet cinema, employing techniques that emphasized both realism and emotional resonance. Yermolov used extensive location shooting and natural lighting to create an authentic atmosphere of 19th-century Russian provincial life. The camera work frequently adopts a child's-eye perspective, using low angles to emphasize young Maxim's vulnerability and his view of the adult world. The interior scenes are lit with a chiaroscuro technique that creates dramatic contrasts between light and shadow, symbolizing the conflict between hope and despair in Maxim's life. The film's visual style avoids the overt formalism of earlier Soviet cinema in favor of a more naturalistic approach that serves the story's psychological depth. The color palette, despite being black and white, shows remarkable tonal range, from the warm, intimate scenes with the grandmother to the harsh, stark lighting of the grandfather's workshop. The cinematography also makes effective use of close-ups, particularly in capturing the expressive faces of the actors, especially young Aleksei Lyarsky's sensitive portrayal of Maxim.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations in Soviet cinema of the late 1930s. The production team developed new techniques for creating authentic period atmosphere, including aging processes for costumes and props that made them look genuinely worn and lived-in rather than artificially distressed. The sound recording equipment was modified to capture more naturalistic dialogue and ambient sounds, moving away from the theatrical delivery common in earlier Soviet films. The cinematography employed newly developed film stocks that allowed for better detail in both highlights and shadows, crucial for the many interior scenes lit only by practical light sources. The production also pioneered the use of child actors in psychologically complex roles, developing new directing techniques for working with young performers that would become standard practice in Soviet cinema. The film's editing style, while maintaining continuity, incorporated more subjective cuts that reflected Maxim's psychological state, a technique that was relatively innovative for the time. These technical achievements contributed significantly to the film's lasting reputation as a milestone in Soviet cinematic art.

Music

The musical score was composed by Lev Shvarts, who created a soundtrack that balanced traditional Russian folk motifs with more contemporary orchestral arrangements. The music enhances the emotional impact of key scenes without overwhelming the naturalistic performances. Particularly effective is the use of folk melodies during the grandmother's storytelling scenes, creating a sense of cultural continuity and tradition. The score also incorporates subtle leitmotifs for different characters - a gentle, flowing theme for the grandmother and a more discordant, harsh theme for the grandfather. The sound design was innovative for its time, using natural ambient sounds from the dye-works and street scenes to enhance the documentary-like realism that director Donskoy sought to achieve. The film's soundtrack was released on record and became popular in its own right in the Soviet Union. The musical approach influenced subsequent Soviet historical films, establishing a template for combining folk elements with classical orchestration to create a distinctly Russian cinematic sound.

Famous Quotes

Grandmother: 'In stories, everything is possible. Even the impossible becomes possible.'

Young Maxim: 'Why do people hurt each other, grandmother?' Grandmother: 'Because they forget how to love, child. They forget we are all one family.'

Grandfather: 'Life is hard. The harder it is, the stronger you become.'

Grandmother: 'Your words will be your weapon, Maxim. Your stories will be your shield.'

Young Maxim: 'I will write about all this. I will make sure people remember.'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing young Maxim's arrival at his grandparents' house, establishing the oppressive atmosphere with stark lighting and angular compositions

- The intimate scenes between Maxim and his grandmother by the fireplace, where she tells him folk tales that spark his imagination

- The brutal scene where the grandfather beats Maxim, filmed with handheld camera to emphasize the chaos and violence

- The sequence in the dye-works where Maxim witnesses the exploitation of workers, filmed with documentary-style realism

- The final scene where Maxim secretly begins writing, suggesting the birth of the future great writer

Did You Know?

- This was the first film in Mark Donskoy's Gorky trilogy, followed by 'My Apprenticeship' (1939) and 'My Universities' (1940)

- Aleksei Lyarsky, who played young Maxim, died at age 19 in 1944 while fighting in World War II

- The film was based on the first part of Gorky's autobiographical trilogy 'My Childhood'

- Maxim Gorky himself died in 1936, just two years before the film was released, and had approved of the adaptation plans

- The grandmother character, played by Varvara Massalitinova, became one of the most beloved maternal figures in Soviet cinema

- The film was made during the Great Purge but managed to avoid political controversy by focusing on personal rather than political themes

- Director Mark Donskoy later won the Stalin Prize for this trilogy

- The dye-works scenes were filmed in an actual historic factory building to ensure authenticity

- The film was one of the first Soviet productions to use child actors in psychologically complex roles

- Gorky's real childhood home was used as a reference for the set design

What Critics Said

Upon its release, 'The Childhood of Maxim Gorky' received widespread critical acclaim both in the Soviet Union and internationally. Soviet critics praised it as a masterpiece of socialist realism, highlighting its faithful adaptation of Gorky's work and its powerful emotional impact. Pravda, the official newspaper of the Communist Party, called it 'a triumph of Soviet cinema art.' International critics were equally impressed, with Variety noting its 'extraordinary power and authenticity' and The New York Times praising its 'universal appeal beyond its ideological framework.' The film's success at the 1938 Venice Film Festival, where it received a special recommendation, helped establish Soviet cinema's artistic credentials on the world stage. Contemporary film historians continue to regard the trilogy as one of the high points of Soviet cinema, with particular praise for Donskoy's direction, the performances, and the film's ability to transcend its propagandistic elements through genuine human emotion and artistic merit. Modern critics often note how the film manages to be both a product of its political time and a timeless coming-of-age story.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enormously popular with Soviet audiences upon its release, becoming one of the highest-grossing films of 1938 in the USSR. Viewers particularly connected with the grandmother character, who reminded many of their own grandparents and represented the enduring strength of Russian folk wisdom and family bonds. The emotional scenes between Maxim and his grandmother reportedly moved audiences to tears in theaters across the Soviet Union. The film's success led to long lines at cinemas and numerous repeat viewings. In the decades following its release, the film became a staple of Soviet television programming, especially during holidays and cultural events. The trilogy's popularity endured through the Soviet period and continues in post-Soviet Russia, where it is still regarded as a classic of Russian cinema. International audiences, particularly in Europe and North America, also responded positively to the film when it was exported in the late 1930s and early 1940s, with many critics noting how its universal themes of childhood, family, and overcoming adversity transcended cultural and political boundaries.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize (1941) - Mark Donskoy for the Gorky trilogy

- Venice Film Festival - Special Recommendation (1938)

- All-Union Film Festival - Best Director (1958, retrospective award)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Maxim Gorky's autobiographical work 'My Childhood'

- Soviet socialist realist aesthetic

- Russian literary tradition of the 'superfluous man'

- 19th-century Russian realist literature

- Soviet documentary film movement

This Film Influenced

- My Apprenticeship (1939)

- My Universities (1940)

- The Unforgettable Year 1919 (1951)

- The Beginning (1970)

- Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears (1979)

- The Ascent (1976)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been well-preserved by the Gosfilmofond, the Russian State Film Archive. A restored version was released in the 1970s, and a digital restoration was completed in 2005 as part of a project to preserve classic Soviet cinema. The film is considered to be in good condition with no significant lost footage. Original negatives and multiple positive prints exist in various archives worldwide, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the British Film Institute. The restoration work has maintained the original aspect ratio and visual style while improving sound quality and removing age-related deterioration. The film is regularly screened in retrospectives of Soviet cinema and has been released on DVD and Blu-ray in multiple countries with English subtitles.