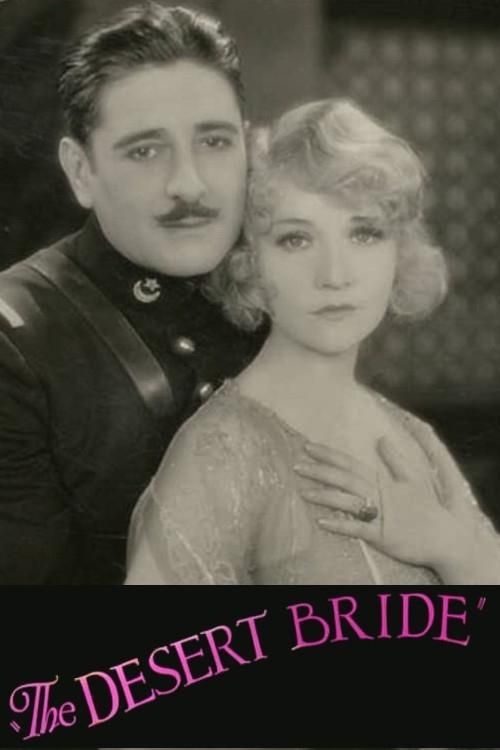

The Desert Bride

Plot

Captain Maurice de Florimont, a French Army intelligence officer, embarks on a dangerous espionage mission in North Africa but is captured by Arab nationalists led by the ruthless Kassim Ben Ali. His beloved Diane Duval, who has followed him to the desert region, is also taken prisoner when she attempts to help him. Both captives endure brutal torture at the hands of their captors but maintain their loyalty to France by refusing to reveal any classified information. As their situation grows increasingly desperate, French military forces launch a dramatic rescue operation, storming the desert fortress where they are held. The climactic battle results in the death of Kassim Ben Ali and the liberation of the brave couple, who emerge from their ordeal with their love and honor intact.

About the Production

The Desert Bride was produced during the transition period between silent films and talkies, making it one of the last major silent releases before the sound revolution completely transformed Hollywood. The film utilized extensive location shooting in California's desert regions to create authentic North African settings, a common practice for Hollywood productions of the era. The production employed numerous extras and elaborate set designs to recreate the desert fortress and military encampments.

Historical Background

The Desert Bride was released in 1928, a year of tremendous change and upheaval in both the film industry and global society. The silent film era was reaching its end as 'The Jazz Singer' (1927) had already demonstrated the commercial potential of sound pictures, and studios were scrambling to convert their productions to the new technology. In terms of global politics, the film reflected the lingering colonial attitudes of Western powers toward North Africa and the Middle East, regions that were largely under European control during this period. The late 1920s also saw the rise of nationalist movements in colonized territories, which may have influenced the film's plot about Arab nationalists resisting French authority. In America, 1928 was a year of economic prosperity just before the devastating Great Depression, and films like The Desert Bride offered audiences escapist entertainment set in exotic locales far from their everyday concerns.

Why This Film Matters

The Desert Bride represents a typical example of the exotic adventure genre that was popular in late silent cinema. While not particularly innovative or groundbreaking, the film contributed to the cultural fascination with 'Oriental' settings and narratives that characterized many Hollywood productions of the era. These films often presented stereotypical and colonialist views of non-Western cultures, reflecting and reinforcing the geopolitical power dynamics of the time. The film's emphasis on Western heroism and the 'civilizing mission' of European powers in 'exotic' lands was a common trope that would persist in cinema for decades. As a product of the final year of major silent film production, The Desert Bride also serves as a historical artifact documenting the techniques, storytelling approaches, and production values of late silent cinema just before the sound revolution transformed the medium completely.

Making Of

The Desert Bride was produced during a pivotal moment in cinema history when the industry was rapidly transitioning from silent films to sound pictures. Director Walter Lang, who would later direct numerous successful musicals and comedies in the sound era, was still honing his craft in the silent medium. The production faced the typical challenges of filming in desert locations, including extreme temperatures, sandstorms, and the logistical difficulties of transporting cast, crew, and equipment to remote shooting sites. Betty Compson, one of the highest-paid actresses of the era, brought star power to the production and likely demanded significant creative input. The film's action sequences and torture scenes would have required careful choreography and camera work to convey intensity without graphic detail, as per the censorship standards of the time. The production design team created elaborate sets to simulate North African architecture, combining on-location shooting with studio work to achieve the desired exotic atmosphere.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Desert Bride would have employed techniques typical of late silent films, including dramatic lighting, careful composition, and the use of tinting to enhance mood and atmosphere. The desert locations would have offered opportunities for striking visual compositions, utilizing the vast landscapes and dramatic lighting conditions of the California desert. The camera work likely emphasized the scale of the settings and the spectacle of the action sequences, particularly the climactic fortress assault. Interior scenes would have featured the dramatic chiaroscuro lighting that characterized silent film melodrama, with careful attention to visual storytelling through composition and actor positioning. The cinematographer would have worked to create visual contrast between the 'civilized' European characters and the 'exotic' Arab settings, reinforcing the film's colonial themes through visual means.

Innovations

The Desert Bride did not introduce any major technical innovations but would have utilized the most advanced filmmaking techniques available in 1928. The production likely employed mobile cameras to capture the desert action sequences, though the equipment of the era was heavy and cumbersome compared to later decades. The film may have utilized special effects techniques such as matte paintings or miniatures to enhance the fortress settings and battle sequences. The desert filming would have required specialized equipment to protect cameras and film from sand and heat, representing a technical challenge for the production crew. As a late silent film, it may have incorporated some synchronized sound effects or musical elements, as hybrid films were briefly produced during the transition period before fully synchronized dialogue became standard.

Music

As a silent film, The Desert Bride would have been accompanied by musical scores performed live in theaters during its original run. The musical accompaniment would have varied by theater size and location, ranging from solo piano performances in smaller venues to full orchestral arrangements in prestigious movie palaces. The score would have followed the conventions of silent film accompaniment, with romantic themes for the love scenes, dramatic and militaristic music for the action sequences, and 'exotic' or 'Oriental' motifs for scenes featuring the Arab characters. The music would have been synchronized with the on-screen action to enhance emotional impact and narrative clarity, with cue sheets provided to theater musicians to ensure appropriate timing and mood. Some larger theaters might have even employed sound effects specialists to create additional auditory atmosphere for key scenes.

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic rescue sequence where French troops storm the desert fortress, featuring elaborate battle choreography and dramatic rescues of the tortured protagonists. The torture scenes, while restrained by 1920s standards, would have provided dramatic tension showcasing the protagonists' resistance and loyalty. The initial capture sequence in the desert, establishing the dangerous setting and introducing the conflict between the French officers and Arab nationalists.

Did You Know?

- This was one of director Walter Lang's early films, made before he would become a prominent director at 20th Century Fox in the 1930s and 1940s.

- Betty Compson, who played Diane Duval, was already an established star by 1928 and had received an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress for 'The Barker' the same year.

- The film was released just weeks before the Wall Street Crash of 1929, during the final peak of the silent film era.

- Edward Martindel, who portrayed the villain Kassim Ben Ali, was a character actor who appeared in over 200 films between 1915 and 1940.

- The Desert Bride was one of Columbia Pictures' attempts to compete with major studios by producing exotic adventure films with established stars.

- The film's themes of colonialism and Western intervention in North Africa reflected common attitudes and geopolitical concerns of the late 1920s.

- Allan Forrest, who played Captain de Florimont, was a silent film star who struggled to transition to talkies and his career declined in the 1930s.

- The film was likely shot on the same California desert locations used for numerous other Hollywood productions set in exotic locales.

- No complete prints of The Desert Bride are known to survive in major film archives, making it one of the many lost films of the silent era.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of The Desert Bride appears to have been modest, with reviewers acknowledging it as a competent but unremarkable example of the exotic adventure genre. The trade publications of the era likely praised Betty Compson's performance and the film's production values while noting that the plot followed familiar conventions. Modern critical assessment is virtually nonexistent due to the film's apparent lost status, preventing contemporary scholars and critics from evaluating its merits. Based on similar films of the period, it would have been judged primarily on its entertainment value, spectacle, and the performances of its stars rather than any artistic innovation or social commentary.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception of The Desert Bride in 1928 would have been influenced by several factors including Betty Compson's star power, the public's appetite for exotic adventure stories, and the novelty of desert settings. As one of the last major silent releases before the sound revolution completely took over, it may have attracted audiences who preferred traditional silent cinema or were curious about the format before it disappeared entirely. The film's mix of romance, action, and exotic settings would have appealed to mainstream audiences seeking entertainment and escapism during the prosperous final months before the Great Depression. However, with the rapid adoption of sound technology, films like The Desert Bride were quickly overshadowed by the new 'talkies,' and their audience appeal diminished rapidly in 1929 and beyond.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Sheik (1921)

- Beau Geste (1926)

- The Son of the Sheik (1926)

- Other exotic adventure films of the 1920s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Desert Bride is considered a lost film, with no complete prints known to exist in major film archives including the Library of Congress, the Museum of Modern Art, or the UCLA Film & Television Archive. Only fragments or promotional materials may survive, as is common with many Columbia Pictures productions from the silent era. The film was likely lost due to the deterioration of nitrate film stock, the common practice of destroying silent films after their theatrical run, or the 1930s Columbia Pictures studio fire that destroyed many of their early productions. The loss of The Desert Bride represents part of the broader tragedy of silent film heritage, with an estimated 75-90% of all silent films considered lost.