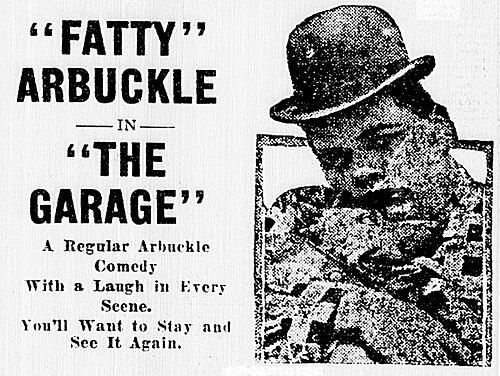

The Garage

Plot

Roscoe 'Fatty' Arbuckle and Buster Keaton play incompetent mechanics and firefighters operating a combined garage and fire station. In the first half of the film, they receive a luxury automobile for cleaning and proceed to completely destroy it through a series of increasingly disastrous mishaps, including filling the engine with gasoline instead of oil and accidentally setting parts of the car on fire. The second half finds the duo responding to a false alarm, leaving their station unattended, only to return and discover their own building is engulfed in flames. Their frantic and chaotic attempts to extinguish the blaze result in more destruction than salvation, culminating in a spectacular display of physical comedy that showcases both performers' exceptional timing and stunt work.

About the Production

This was one of the final collaborations between Arbuckle and Keaton before Keaton began his solo career. The fire scenes were filmed using real fire with minimal safety precautions, typical of the era. The luxury car destroyed in the film was reportedly a genuine vehicle, not a prop. The production utilized the same fire station set that had been used in previous Arbuckle comedies, modified for this specific film.

Historical Background

1920 was a pivotal year in American history, marking the beginning of the Jazz Age and the dawn of Prohibition. The film industry was transitioning from the chaotic early years to a more structured studio system, with Hollywood firmly established as the entertainment capital of the world. The post-World War I economic boom created a thriving market for entertainment, and comedy films were particularly popular as audiences sought lighthearted escapism. This period also saw the rise of the feature film, though comedy shorts remained a staple of theater programs. The film industry was still largely unregulated, allowing filmmakers considerable creative freedom but also leading to dangerous working conditions, as evidenced by the real fire effects used in 'The Garage'.

Why This Film Matters

'The Garage' holds significant importance in film history as one of the final collaborations between two comedy legends. It represents a transitional moment in American comedy, bridging the era of slapstick dominated by figures like Arbuckle and the more sophisticated physical comedy that Keaton would perfect in his solo career. The film exemplifies the innovation and creativity of early Hollywood comedy, showcasing the development of visual gags, physical comedy techniques, and narrative structure that would influence generations of comedians. Its preservation of the Arbuckle-Keaton partnership provides valuable insight into the evolution of American comedy and the collaborative nature of early filmmaking. The film also serves as a time capsule of 1920s American culture, depicting the fascination with automobiles and the heroic status of firefighters during this period of rapid technological and social change.

Making Of

The production of 'The Garage' represented the culmination of the creative partnership between Arbuckle and Keaton, who had developed a remarkable on-screen chemistry through their previous collaborations. Arbuckle, an established star and successful director, mentored the younger Keaton, who would soon become one of cinema's greatest comedy innovators. The filming of the fire scenes was particularly challenging, as the crew used real gasoline and fire effects without modern safety equipment. Both performers insisted on doing their own stunts, including sequences where they were nearly engulfed in flames. The relationship between Arbuckle and Keaton was reportedly warm and collaborative, with Arbuckle encouraging Keaton's creative input and allowing him to develop his distinctive comedy style. The film was shot quickly, as was typical for comedy shorts of the era, with most scenes completed in one or two takes to maintain spontaneity and energy.

Visual Style

The cinematography by George Peters, a frequent Arbuckle collaborator, demonstrates the sophisticated visual techniques being developed in comedy films of this era. The camera work is notably dynamic for its time, with tracking shots following the chaotic action and carefully composed wide shots that capture the full scope of the physical comedy. The fire scenes utilize dramatic lighting effects, with the flames providing natural, high-contrast illumination that enhances the visual spectacle. The photography maintains clear visibility of the performers' expressions and movements during the most complex action sequences, a testament to the technical skill of the cinematographer. The film also employs effective use of depth in the garage set, allowing for multi-layered gags to occur simultaneously within the frame.

Innovations

The film demonstrates several notable technical achievements for its time, particularly in its execution of practical effects. The fire sequences, while dangerous, were remarkably well-executed for 1920, showing sophisticated understanding of controlled fire effects on film sets. The destruction of the automobile involved complex mechanical gags that required precise timing and coordination. The film also showcases advanced editing techniques for the era, with rapid cuts during the action sequences that maintain comedic rhythm and pacing. The use of multiple camera angles and movements, particularly during the fire scenes, was innovative for comedy shorts of this period. The production design of the garage set was particularly elaborate, featuring working mechanical elements that enhanced the physical comedy and allowed for more complex gags.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Garage' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical score would have been compiled from popular classical pieces, theater music, and original compositions by the theater's musical director. The fire sequences would have been accompanied by dramatic, fast-paced music to heighten the excitement, while the more comedic moments would have used lighter, more whimsical selections. Modern restorations of the film have featured newly composed scores by silent film specialists, who attempt to recreate the musical experience of 1920s cinema while using contemporary orchestration techniques. The absence of recorded dialogue places greater emphasis on the visual comedy and the musical accompaniment to convey mood and enhance the comedic timing.

Famous Quotes

(As a silent film, there are no spoken quotes, but notable intertitles include: 'We'll clean it so it will look like new!' and 'Fire! Fire! The garage is burning!')

Memorable Scenes

- The sequence where Arbuckle and Keaton attempt to clean the luxury car, progressively destroying it through their incompetence; the climactic fire scene where they return to find their own building burning and attempt to fight the fire with disastrous results; the moment where they use gasoline instead of oil in the car's engine, leading to explosive consequences

Did You Know?

- This was the fourteenth and final film in the Arbuckle-Keaton series before Keaton launched his independent production company

- The fire scenes were particularly dangerous, with both performers doing their own stunts amidst real flames

- Molly Malone, who played the love interest, was Arbuckle's frequent co-star and appeared in many of his films

- The film showcases early examples of what would become Keaton's signature 'stone face' comedy style

- The garage set was built specifically for this film and was one of the most elaborate sets used in the Arbuckle-Keaton collaborations

- The car destroyed in the film was a Packard Twin Six, one of the most expensive luxury cars of its time

- The film was released just months before Prohibition began, marking the end of an era in American culture

- Arbuckle directed, wrote, and starred in the film, demonstrating his remarkable versatility as a filmmaker

- The fire hose sequences required precise timing and coordination between the two comedians

- This film is often cited by film historians as representing the peak of the Arbuckle-Keaton creative partnership

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'The Garage' for its inventive gags and the chemistry between Arbuckle and Keaton. The film was reviewed favorably in trade publications like Variety and Motion Picture News, which highlighted its spectacular fire sequences and the comedians' timing. Modern critics and film historians regard it as one of the strongest entries in the Arbuckle-Keaton series, noting how it showcases both performers at their creative peak. The film is often cited in academic studies of early comedy as an example of sophisticated visual storytelling and physical comedy technique. Contemporary reviewers particularly appreciate the film's well-structured two-part narrative and the seamless integration of its various comedic set pieces.

What Audiences Thought

The film was highly popular with contemporary audiences, who were enthusiastic fans of both Arbuckle and Keaton. Theater owners reported strong attendance for screenings of 'The Garage', and it performed well in both urban and rural markets. The combination of automobile humor and fire-fighting action appealed to a broad cross-section of the moviegoing public. Audiences particularly responded to the spectacular fire sequences and the destructive comedy involving the luxury car. The film's success contributed to Arbuckle's status as one of the most popular and bankable stars of the early 1920s. Modern audiences, when exposed to the film through retrospectives and archival screenings, continue to appreciate its physical comedy and historical significance as a collaboration between two comedy masters.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Mack Sennett comedies

- Chaplin's early shorts

- Keystone Kops films

This Film Influenced

- Keaton's 'The General' (1926)

- Laurel and Hardy shorts

- Three Stooges comedies

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the Library of Congress collection and has been restored by several film archives. Multiple copies exist in various film archives worldwide, including the Museum of Modern Art and the UCLA Film & Television Archive. The restoration efforts have successfully maintained the film's visual quality, though some minor deterioration is evident in existing prints. The film is considered to be in good preservation condition for a title of its age, with no missing footage reported.