The Great Train Robbery

"A thrilling tale of crime and pursuit on the Western frontier"

Plot

The film opens with bandits forcing a telegraph operator to stop a train by holding him at gunpoint and tying him up. The train is then boarded by the outlaws who systematically rob the passengers of their valuables at gunpoint, with one bandit even forcing a young woman to dance for their amusement. After successfully looting the train, the criminals escape on horseback with their stolen goods. Meanwhile, the bound telegraph operator manages to free himself and alert the local authorities, who quickly form a posse to pursue the fleeing bandits. The film culminates in an extended chase sequence through rugged terrain, ending with a dramatic gunfight where the posse ultimately defeats the outlaws and recovers the stolen money.

About the Production

Filmed over two days in November 1903, using both studio sets and real outdoor locations. The production utilized actual trains and railroad employees, with some scenes filmed on moving trains. The famous scene where a bandit shoots at the camera was filmed last and could be shown at either the beginning or end of the film at the exhibitor's discretion.

Historical Background

The Great Train Robbery emerged during the transformative period of early cinema when filmmakers were transitioning from simple actualities and trick films to more complex narrative storytelling. In 1903, the film industry was still in its infancy, with most productions lasting only a few minutes and consisting of single shots or simple scenarios. The Western genre was just beginning to emerge as America's first film genre, capitalizing on public fascination with the recently 'closed' frontier. The film was produced during the height of the Edison Trust's dominance of American cinema, when the Motion Picture Patents Company controlled film production and distribution. This period saw rapid technological innovations in camera equipment and film stock, enabling longer films and more ambitious productions. The popularity of train-themed entertainment reflected America's ongoing fascination with railroads, which had revolutionized transportation and commerce in the late 19th century.

Why This Film Matters

The Great Train Robbery fundamentally changed the language of cinema by demonstrating that films could tell complex stories with multiple locations, character development, and dramatic action sequences. It established many conventions of the Western genre that would persist for decades, including the clear moral dichotomy between lawmen and outlaws, the use of rugged landscapes, and the emphasis on action and violence. The film's commercial success proved that audiences would sit through longer narrative films, paving the way for the feature-length format. Its innovative editing techniques, particularly the use of parallel action to build suspense, influenced countless filmmakers and became standard practice in narrative cinema. The film also established the star system, as Gilbert M. Anderson's performance led to his career as 'Broncho Billy,' the first cowboy star. Perhaps most importantly, it demonstrated cinema's potential as a storytelling medium rather than just a novelty or technical curiosity.

Making Of

Edwin S. Porter, working for Thomas Edison's company, drew inspiration from both a real 1900 train robbery in Wyoming and a popular stage play. The production was ambitious for its time, requiring coordination between multiple filming locations and complex editing. Porter experimented with parallel editing, cross-cutting between the telegraph office, the train robbery, and the pursuing posse to build suspense. The cast was composed largely of theater actors and Edison studio regulars, with Gilbert M. Anderson playing three different roles. The outdoor sequences presented significant technical challenges, as the heavy camera equipment had to be transported to remote locations and operated without modern conveniences. The famous scene of the bandits throwing a passenger from the moving train was performed by a stuntman who actually jumped from a slowly moving train onto mattresses hidden in the grass.

Visual Style

The cinematography was revolutionary for its time, utilizing multiple camera positions and locations to create visual variety and narrative clarity. Porter employed static camera shots from various angles, including eye-level views of the action and dramatic compositions that emphasized the scale of the Western landscape. The film used both interior shots in studio sets and exterior location photography, creating a sense of realism that was unusual for the period. The famous final shot of the bandit firing at the camera used a close-up that created an unprecedented sense of direct address to the audience. The cinematography also included innovative techniques such as matte shots and in-camera effects to create the illusion of the train in motion. The film's visual style established many conventions of Western cinematography that would persist for decades.

Innovations

The Great Train Robbery introduced numerous technical innovations that would become standard in filmmaking. It was one of the first films to use parallel editing, cutting between different locations to create suspense and suggest simultaneous action. Porter employed jump cuts and continuity editing to maintain narrative flow between shots. The film also featured one of the earliest uses of location shooting mixed with studio sets, creating a more realistic environment than purely studio-bound productions. The production utilized actual moving trains and real railroad equipment, requiring complex coordination between the film crew and railroad personnel. The film's composite effects, particularly in the scene showing the train moving through the landscape, were achieved through innovative matte photography techniques. The film also demonstrated sophisticated use of camera placement and framing to create dramatic emphasis and guide audience attention.

Music

The film was originally silent, as all films were in 1903, but exhibitors typically provided live musical accompaniment. Edison Manufacturing Company distributed suggested musical cues with the film, recommending specific pieces for different scenes. Typical accompaniment included popular songs of the era, classical pieces, and specially composed mood music. The chase sequences were often accompanied by fast-paced, energetic music to heighten the excitement, while the more dramatic moments used slower, more somber pieces. Some theaters employed small orchestras, while others used a single pianist or organist. The musical accompaniment was crucial to the viewing experience, as it helped convey emotion and build suspense in the absence of dialogue.

Famous Quotes

(Title card) 'The Great Train Robbery'

(Title card) 'Bandits compel the telegraph operator to set the signals so the express train will be stopped'

(Title card) 'Bandits hold up the train and rob the passengers'

(Title card) 'The telegraph operator escapes and gives the alarm'

(Title card) 'A lively chase and the capture of the bandits'

Memorable Scenes

- The iconic opening scene where bandits force the telegraph operator to stop the train at gunpoint, establishing the film's dramatic tension and setting up the central conflict. The sequence uses close-ups and careful staging to create a sense of genuine menace and desperation.

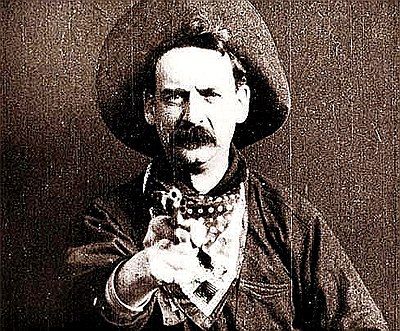

- The climactic scene where a bandit fires his pistol directly at the camera, a shocking moment that reportedly caused audiences to scream and duck. This fourth-wall-breaking shot became one of the most famous images in early cinema.

- The extended chase sequence through the forest, where the posse pursues the fleeing bandits on horseback. This sequence showcased Porter's innovative editing techniques and ability to build suspense through parallel action.

- The scene where bandits throw passengers from the moving train, which was considered shocking and realistic for its time and demonstrated the film's willingness to push boundaries of on-screen violence.

Did You Know?

- Often incorrectly cited as the first narrative film, it was actually one of the first American narrative films to use multiple locations and sophisticated editing techniques

- The iconic final shot of a bandit firing his pistol directly at the camera terrified early audiences who had never seen such a direct confrontation with the camera

- The film was shot in just two days but required extensive post-production editing, which was revolutionary for the time

- Gilbert M. Anderson, who played multiple roles including one of the bandits, later became famous as 'Broncho Billy' Anderson, the first Western movie star

- The film was so popular that it was often shown multiple times daily in vaudeville theaters and nickelodeons

- Edison initially sued competitors who made unauthorized copies, establishing early film copyright precedents

- The film used 14 distinct shots, an unprecedented number for a film of its era

- Real railroad employees were used as extras, and the train was an actual working locomotive borrowed from the railroad

- The dance scene where bandits force passengers to dance was considered shocking and risqué for 1903 audiences

- The film was distributed internationally and was particularly popular in Europe, influencing early filmmakers like Georges Méliès

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics and trade publications hailed the film as a masterpiece of the new medium. The New York Dramatic Mirror praised its 'thrilling realism' and 'perfect execution,' while The Moving Picture World called it 'the most remarkable and sensational picture ever produced.' Modern critics universally recognize it as a landmark achievement in film history. The American Film Institute ranks it among the most important American films ever made, and film scholars cite it as a crucial turning point in the development of narrative cinema. Critics particularly note Porter's innovative editing techniques and his ability to build suspense through cross-cutting. The film is frequently studied in film schools as an example of early cinematic language and the birth of the American action film.

What Audiences Thought

The film was an immediate sensation with audiences, who were thrilled by its action sequences and realistic violence. Reports from theaters described audiences gasping, screaming, and even ducking during the scene where the bandit fires directly at the camera. Many exhibitors reported that the film was so popular that they had to show it multiple times daily to meet demand. The film's success helped establish the nickelodeon as a viable entertainment venue and demonstrated that there was a market for longer, more sophisticated films. Some audience members were reportedly shocked by the violence, particularly the scene where passengers are thrown from the moving train, but this controversy only increased public interest. The film's popularity extended internationally, with European audiences responding enthusiastically to its American Western setting and action sequences.

Awards & Recognition

- National Film Registry selection (1990)

- Library of Congress preservation

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Great Train Robbery of 1900 (real event)

- Scott Marble's stage play 'The Great Train Robbery' (1896)

- British film 'A Daring Daylight Burglary' (1903)

- Georges Méliès' narrative films

- Edison's earlier narrative shorts

This Film Influenced

- The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906)

- Broncho Billy films (1910s)

- D.W. Griffith's 'The Battle at Elderbush Gulch' (1913)

- John Ford's early Westerns

- Stagecoach (1939)

- The Good, The Bad and The Ugly (1966)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is well-preserved with multiple surviving prints in various archives. The Library of Congress holds a complete 35mm print in their collection, and the film was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry in 1990. Several restoration projects have been undertaken, including a 2003 restoration for the film's 100th anniversary. The film exists in both its original 12-minute version and in various shortened versions that were created for different exhibition purposes. Digital copies are widely available for scholarly and public viewing.