The Iron Horse

"The Romance of the Iron Trail!"

Plot

The Iron Horse tells the epic story of the construction of the first transcontinental railroad across America in the 1860s. The film follows Davy Brandon, whose father was killed by Cheyenne warriors while surveying a route for the railroad, leaving Davy orphaned and determined to complete his father's dream. Years later, Davy becomes a Pony Express rider and eventually joins the Union Pacific railroad construction, facing numerous obstacles including sabotage, natural disasters, and conflicts with Native American tribes. Along the way, he competes with his childhood friend and rival for the affections of Miriam Marsh, the daughter of a railroad contractor. The film culminates in the historic meeting of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads at Promontory Summit, Utah, symbolizing the unification of America.

About the Production

The film was shot over 8 months with a crew of 500 people and 3,000 extras. Real trains were used, including the historic locomotive 'The Jupiter' replica. Ford insisted on authentic locations, moving the entire company to remote desert areas. The film featured dangerous stunt work with real train crashes and explosions, resulting in several injuries among crew members.

Historical Background

The Iron Horse was produced during the Roaring Twenties, a period of rapid technological advancement and economic prosperity in America. The film tapped into contemporary nostalgia for the frontier era, which had ended only 50 years earlier. It reflected 1920s America's fascination with progress and industrialization while romanticizing the recent past. The film's themes of national unity and manifest destiny resonated strongly with audiences still recovering from World War I and experiencing unprecedented immigration and urbanization. Its production coincided with the 50th anniversary of the transcontinental railroad's completion, making it particularly timely.

Why This Film Matters

The Iron Horse established the template for the epic Western genre and influenced countless subsequent films. It was one of the first films to present the American West as a subject for serious historical drama rather than mere entertainment. The film's success proved that audiences would respond to longer, more ambitious historical epics, paving the way for films like 'The Birth of a Nation' and 'Gone with the Wind.' It also established John Ford as a major director who would go on to define the Western genre. The film's portrayal of Native Americans, while stereotypical by modern standards, was considered relatively balanced for its time, showing both their resistance to encroachment and their eventual defeat.

Making Of

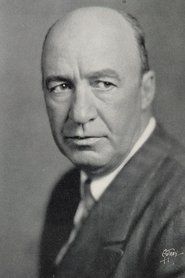

John Ford, then known primarily for his Western shorts, was given this ambitious project by Fox studio head William Fox. The production was massive in scale, requiring the construction of entire towns, miles of railroad track, and the coordination of thousands of extras. Ford faced numerous challenges including extreme weather conditions in the desert locations, equipment failures, and safety concerns during the dangerous stunt sequences. The famous train crash scene required precise timing and resulted in the destruction of actual locomotives. Ford insisted on authenticity, hiring consultants who had worked on the actual transcontinental railroad. The film's success was largely due to Ford's innovative use of long shots and landscape cinematography, which gave the production an epic scope rarely seen in silent films.

Visual Style

The cinematography by George Schneiderman was groundbreaking for its time, featuring sweeping panoramic shots of the American landscape that emphasized the vast scale of the railroad project. Ford used innovative camera techniques including tracking shots from moving trains and aerial views achieved by mounting cameras on tall platforms. The film's visual style emphasized the contrast between the untamed wilderness and the technological progress of the railroad. Schneiderman's use of natural light, particularly in the desert sequences, created stark, dramatic images that became hallmarks of the Western genre. The film also featured impressive night photography for the era, using magnesium flares to illuminate large exterior scenes.

Innovations

The Iron Horse featured numerous technical innovations for its time, including the use of multiple cameras to capture complex action sequences from different angles simultaneously. The film's train crash sequence was particularly groundbreaking, requiring precise timing and the use of specialized camera mounts to safely capture the destruction. Ford employed early forms of matte painting to extend the scope of certain shots and used forced perspective to make the railroad construction appear even more massive. The film also featured some of the earliest examples of location sound recording, with crews capturing ambient sounds to be used as reference for the musical score.

Music

As a silent film, The Iron Horse was originally accompanied by live musical scores performed by theater orchestras. The suggested cue sheet compiled by James Bradford included adaptations of popular songs like 'Oh! Susanna' and 'Camptown Races' along with classical pieces. The score was designed to enhance the film's epic scope, with full orchestral passages for the train sequences and romantic themes for the love story. Modern restorations have featured newly composed scores by musicians like Timothy Brock, who created original music that respects the film's 1920s context while appealing to contemporary audiences.

Famous Quotes

Nothing can stop the iron horse now!

This railroad isn't just about steel and steam - it's about bringing a nation together

My father died for this railroad, and I'll see it through if it takes my last breath

The West will never be the same after this iron horse tears through it

Memorable Scenes

- The spectacular train crash sequence where two locomotives collide in a planned demolition

- The buffalo stampede scene with thousands of animals thundering across the plains

- The final Golden Spike ceremony at Promontory Summit with thousands of extras

- The opening sequence showing the surveying party's encounter with the Cheyenne

- The romantic meeting between Davy and Miriam at the railroad camp

Did You Know?

- This was John Ford's first major success and established his reputation as a serious director

- The film used over 7,000 extras, including actual Native Americans from the Cheyenne and Crow tribes

- The two-fingered villain was played by actor Fred Kohler, who wore a special glove to create the effect

- Real buffalo were filmed for the buffalo stampede sequence, with some animals actually killed during filming

- The film's success led to Ford being given more creative control over his future projects

- A full-scale replica of Promontory Summit was built for the final scene

- The film was one of the most expensive productions of its time

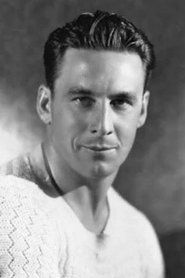

- George O'Brien performed many of his own stunts, including riding alongside moving trains

- The original nitrate negative was lost, but the film was reconstructed from multiple sources

- The film's premiere was attended by President Calvin Coolidge

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised The Iron Horse for its ambitious scope, authentic detail, and spectacular action sequences. The New York Times called it 'a magnificent achievement in motion picture art' while Variety noted its 'unprecedented scale and historical importance.' Modern critics recognize the film as a landmark in cinema history, particularly for Ford's use of landscape and his development of the visual language of the Western. The film is often cited as a precursor to Ford's later masterpieces like 'Stagecoach' and 'The Searchers.' Critics today note that while some elements appear dated, particularly its treatment of Native Americans, the film's technical achievements and epic vision remain impressive.

What Audiences Thought

The Iron Horse was a massive commercial success, becoming one of the highest-grossing films of 1924. Audiences were thrilled by its spectacular action sequences, particularly the train crashes and buffalo stampede. The film's romantic subplot appealed to female viewers, while its historical themes resonated with older audiences who had lived through the railroad era. The film played for months in major cities and was particularly popular in the American West, where many viewers recognized locations and events from their own regional history. Its success established George O'Brien as a major star and proved that historical epics could be commercially viable.

Awards & Recognition

- Photoplay Medal of Honor 1924

- Academy Honorary Award (1930 retrospective)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Covered Wagon (1923)

- D.W. Griffith's historical epics

- Contemporary dime novels about the West

- Historical accounts of the Golden Spike ceremony

This Film Influenced

- Union Pacific (1939)

- How the West Was Won (1962)

- Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

- Stagecoach (1939)

- The Great Train Robbery (1903) remakes

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The original nitrate negative of The Iron Horse was lost in a 1937 Fox vault fire. However, the film has been preserved through reconstruction from various sources including duplicate negatives and distribution prints held in archives worldwide. The most complete restoration was completed in 2006 by the Museum of Modern Art and 20th Century Fox, combining elements from five different sources. The restored version premiered at the 2006 Cannes Film Festival and is now preserved in the National Film Registry.