The Lost Letter

"A journey to Hell and back for a lost letter!"

Plot

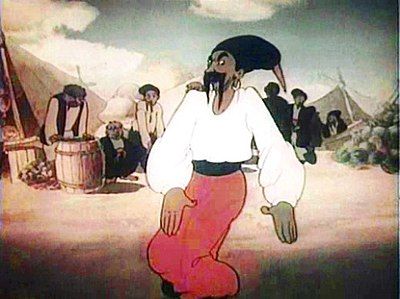

The story follows Vakula, a Cossack messenger tasked with delivering an important letter from his village to the Tsarina in Saint Petersburg. During his journey, Vakula tucks the precious letter into his hat for safekeeping and stops to rest at an inn overnight. While he sleeps, a mischievous band of demons steals his hat containing the letter, forcing Vakula to embark on a perilous journey to Hell to retrieve it. In Hell, he encounters various demonic creatures and must use his wit and courage to outsmart them and recover the letter. After successfully retrieving the hat, Vakula continues his journey to deliver the letter to the Tsarina, overcoming numerous obstacles along the way. The film combines Gogol's satirical portrayal of Ukrainian folk culture with fantastical elements, creating a whimsical adventure that showcases the triumph of human ingenuity over supernatural forces.

About the Production

The film was created during the final year of World War II, making its production particularly challenging due to resource shortages and the evacuation of many animation facilities. The Brumberg sisters (Zinaida and Valentina) directed this landmark film, pioneering cel animation techniques in the Soviet Union. The team had to develop their own animation methods as Western techniques were not accessible during the war period. The film's production spanned approximately two years, with careful attention to preserving Ukrainian cultural elements from Gogol's original story while adapting it for animation.

Historical Background

The film was produced in 1945, a pivotal year marking the end of World War II. The Soviet Union was recovering from immense devastation, and cinema was seen as a vital tool for cultural restoration and morale building. Stalin's cultural policies emphasized accessible, optimistic art that celebrated Soviet values while drawing from Russian and Ukrainian literary traditions. The choice to adapt Gogol's work reflected the regime's endorsement of classic literature that could be interpreted to support socialist ideals. The film's production during wartime scarcity demonstrated the Soviet commitment to cultural development even under extreme conditions. This period also saw the consolidation of the Soviet animation industry under state control, with Soyuzmultfilm becoming the central hub for animated production. The film's release coincided with the beginning of the Cold War, making it one of the first post-war cultural exports from the Soviet Union.

Why This Film Matters

'The Lost Letter' represents a watershed moment in Soviet animation history, establishing cel animation as a viable medium for feature-length productions in the USSR. The film demonstrated that animation could successfully adapt classic literature, opening doors for future literary adaptations. Its blend of Ukrainian folklore, satirical elements, and fantasy created a template for Soviet animated features that would influence decades of production. The film's success helped legitimize animation as serious art form rather than just children's entertainment. It also preserved and popularized Gogol's work for new generations, contributing to the cultural education of Soviet citizens. The film's technical innovations in multi-layered cel animation and color techniques advanced the craft within the Soviet animation community. Its international distribution helped showcase Soviet artistic achievements abroad during the early Cold War period.

Making Of

The production of 'The Lost Letter' faced extraordinary challenges during World War II. Many animators were drafted into military service, and those remaining worked in difficult conditions with limited resources. The Brumberg sisters had to innovate with available materials, often creating their own animation supplies. The team worked in a converted building in Moscow, as the main Soyuzmultfilm facilities had been damaged during the war. Voice recording was particularly challenging due to equipment shortages, requiring multiple takes and creative sound engineering. The animators studied Ukrainian folk art and costumes extensively to ensure cultural authenticity in the character designs. The Hell sequences required extensive storyboarding and experimentation with lighting effects to create the otherworldly atmosphere. Despite these challenges, the production team maintained high artistic standards, resulting in a film that pushed the boundaries of Soviet animation.

Visual Style

The film's visual style represents a breakthrough in Soviet animation cinematography, employing sophisticated multi-plane camera techniques to create depth and dimension. The animation team used layered cels to achieve parallax effects, particularly in the Hell sequences where floating elements and layered backgrounds created a sense of otherworldly space. Color palettes were carefully chosen to distinguish between the earthly Ukrainian village scenes (warm, earthy tones) and the supernatural Hell sequences (vibrant, contrasting colors). The cinematography incorporated traditional Ukrainian folk art motifs into the background designs, creating a distinctive visual identity. Camera movements were more dynamic than previous Soviet animations, including tracking shots and zooms that enhanced the storytelling. The lighting effects, especially in the supernatural sequences, were groundbreaking for Soviet animation, using color gradients and shadow techniques to create atmospheric depth.

Innovations

The film pioneered cel animation techniques in the Soviet Union, introducing methods that had been developed in the West but adapted to Soviet conditions. The animation team developed a special registration system for multi-layered cels that allowed for complex depth effects without Western equipment. Color processing techniques were innovated to achieve vibrant hues despite wartime pigment shortages. The film introduced sophisticated character animation techniques, including more fluid movement and expressive facial animations than previous Soviet productions. The Hell sequences featured experimental lighting effects using multiple exposure techniques and color filters. The team created custom animation stands and camera rigs to achieve specific visual effects. The film's success in these technical areas established new standards for Soviet animation production and influenced subsequent projects at Soyuzmultfilm.

Music

The musical score was composed by Soviet composer Nikita Bogoslovsky, who adapted Ukrainian folk melodies into the orchestral arrangements. The soundtrack incorporates traditional Ukrainian musical instruments and rhythms, enhancing the cultural authenticity of the adaptation. Voice acting was performed by prominent Soviet theater actors, including Sergei Martinson, Mikhail Yanshin, and Boris Livanov, who brought theatrical gravitas to the animated characters. Sound effects were innovative for the time, using creative Foley techniques to produce the supernatural elements and character movements. The musical numbers, particularly those featuring the demons, combined folk melodies with orchestral arrangements that reflected the film's blend of tradition and fantasy. The soundtrack was recorded using limited wartime equipment, yet achieved remarkable clarity and dynamic range. The film's theme music became recognizable to Soviet audiences and was later used in documentaries about Soviet animation history.

Famous Quotes

Even in Hell, a clever Cossack can find his way!

A letter to the Tsarina is more precious than gold, but even gold can't buy you out of the devil's grasp!

When demons steal your hat, you must go to Hell to get it back - such is the way of our world!

In Ukraine, even the devil has a sense of humor!

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic sequence where Vakula descends into Hell, with swirling red and orange mists creating a terrifying yet beautiful otherworldly atmosphere

- The comical scene where the demons try on Vakula's hat and argue over who gets to keep the letter

- The final confrontation in Hell where Vakula outsmarts the demons through clever wordplay and quick thinking

- The opening sequence showing the Ukrainian village with detailed folk art backgrounds and traditional costumes

Did You Know?

- This was the first Soviet cel-animated feature film, marking a milestone in Soviet animation history

- The film is based on one of the stories from Nikolai Gogol's 1832 collection 'Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka'

- Director Zinaida Brumberg worked alongside her sister Valentina Brumberg, forming the famous 'Brumberg Sisters' directing duo

- The voice cast included prominent Soviet theater actors, with Sergei Martinson providing multiple character voices

- The demon characters were designed to be more comical than terrifying, reflecting the film's family-friendly approach

- The animation team used a special multi-layered cel technique to create depth in the Hell sequences

- Despite being made during wartime, the film features vibrant colors and elaborate backgrounds

- The film's success helped establish Soyuzmultfilm as the premier animation studio in the Soviet Union

- Original film elements were preserved in the Gosfilmofond archive, though some sequences have deteriorated over time

- The film was one of the first Soviet animations to be exported internationally after the war

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film for its artistic merit and technical innovation, particularly noting its successful adaptation of Gogol's satirical style to animation. The film was highlighted in Soviet film journals as a milestone achievement in the development of national animation. Critics commended the Brumberg sisters for their sensitive handling of Ukrainian cultural elements and their ability to balance humor with fantasy. Western critics, when the film became available internationally, were impressed by its sophisticated animation techniques and distinctive visual style, which differed from American animation of the period. Modern film historians recognize the film as a crucial document of Soviet animation development, noting its influence on subsequent generations of Soviet animators. The film is frequently cited in academic studies of animation history as an example of how national cultural traditions can be preserved and transformed through the medium of animation.

What Audiences Thought

The film was warmly received by Soviet audiences upon its release in 1945, who appreciated its humor, fantasy elements, and familiar literary source material. Children and adults alike enjoyed the colorful animation and the adventurous story, which provided welcome entertainment during the difficult post-war period. The film's success led to multiple re-releases in theaters throughout the late 1940s and 1950s. Audience letters preserved in Soviet archives show particular appreciation for the demon characters and the imaginative depiction of Hell. The film developed a cult following among animation enthusiasts and became a staple of Soviet television programming during holiday seasons. International audiences, when the film was exported, responded positively to its unique visual style and storytelling approach, which differed significantly from Western animation conventions of the era.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize, Second Class (1946) - For outstanding achievement in cinema

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Nikolai Gogol's 'Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka'

- Ukrainian folk tales and legends

- Traditional Ukrainian art and costumes

- Soviet realist art principles

- Early Disney animation techniques (adapted for Soviet use)

This Film Influenced

- The Snow Queen (1957)

- The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish (1950)

- The Enchanted Boy (1955)

- Later Soyuzmultfilm adaptations of classic literature

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved in the Gosfilmofond State Film Archive of Russia, though some original elements show signs of deterioration typical of nitrate film from this period. A restoration project was undertaken in the 1990s to preserve the film for future generations. Digital restoration efforts have continued in the 21st century, with the film now available in restored high-definition format. The original soundtrack has been remastered, though some audio elements remain degraded. The film is considered culturally significant and receives regular preservation attention from Russian film archives.