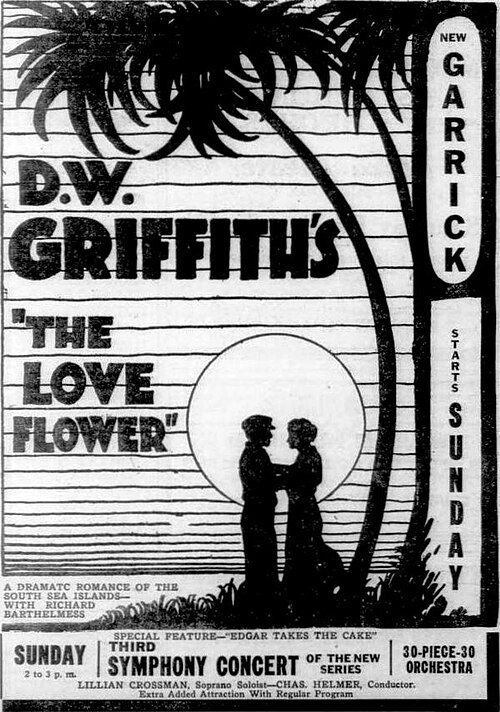

The Love Flower

"A Romance of the South Seas"

Plot

Thomas Bevan, a respectable family man, discovers his wife's infidelity and murders her lover in a crime of passion. Fleeing justice with his young daughter Lucille, he escapes to a remote South Pacific island where they live in isolation for years. A determined detective, Bruce Sanders, relentlessly pursues Bevan, eventually tracking him to the tropical paradise. Sanders is accompanied by a young man named John McCormick who, upon meeting the now-grown Lucille, falls deeply in love with her, creating a complex romantic triangle. The film culminates in a dramatic confrontation where love, justice, and redemption intersect against the backdrop of the exotic island setting.

About the Production

The Love Flower was one of the first American films to shoot extensively on location in the Bahamas, presenting significant logistical challenges for the 1920 production crew. Griffith insisted on authentic tropical settings, leading to a difficult six-week location shoot where cast and crew had to contend with hurricanes, extreme heat, and primitive living conditions. The film's production was notably expensive for its time due to these location requirements, though exact budget figures were not preserved. Griffith's meticulous attention to detail extended to constructing a full-scale tropical village set, complete with native huts and jungle foliage.

Historical Background

The Love Flower was produced in 1919-1920, a pivotal period in American cinema history. This was the era when Hollywood was consolidating its power as the global film capital, and D.W. Griffith was one of its most influential figures. The film was made shortly after World War I, during a time of social change and moral questioning in America. The story of a man committing murder yet finding redemption reflected the era's complex attitudes toward justice and morality. Additionally, the film's production coincided with the formation of United Artists in 1919, which Griffith co-founded alongside Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks. This was also a period when location shooting was becoming more feasible but still extremely challenging, making The Love Flower's tropical setting particularly ambitious for its time.

Why This Film Matters

While not as celebrated as Griffith's major works like Birth of a Nation or Intolerance, The Love Flower represents an important transitional work in his filmography and in early Hollywood cinema. The film demonstrates the industry's growing ambition to move beyond studio confines and embrace authentic locations, a trend that would become increasingly important in the 1920s. It also showcases Griffith's continued experimentation with narrative structure and visual storytelling techniques. The film's treatment of themes like redemption, justice, and romantic love in exotic settings helped establish conventions that would influence countless adventure and romance films in subsequent decades. Additionally, it represents an early example of Hollywood's fascination with tropical paradises as settings for dramatic narratives, a trope that would become a staple of American cinema.

Making Of

The production of The Love Flower was marked by numerous challenges and innovations. D.W. Griffith, at the height of his creative powers, insisted on authentic tropical locations rather than studio sets, a decision that caused considerable hardship for the cast and crew. The company spent six weeks in the Bahamas during the summer of 1919, where they faced hurricanes, malaria concerns, and extreme humidity that affected the film equipment. Griffith's perfectionism led to multiple reshoots and extensive re-editing upon return to California. The film was also notable for Griffith's discovery and promotion of Carol Dempster, with whom he would have both professional and personal relationships in the coming years. The production employed local Bahamian residents as extras and consultants to ensure authenticity in the island sequences, a practice that was relatively uncommon in Hollywood at the time.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Love Flower, credited to G.W. Bitzer and Hendrik Sartov, was particularly notable for its time. The film featured groundbreaking location photography in the Bahamas, capturing the tropical landscape with unprecedented authenticity for a Hollywood production. The cinematographers employed natural lighting techniques to great effect in the outdoor scenes, creating luminous images of the island paradise that contrasted sharply with the darker, more shadowy scenes of the murder and pursuit. The use of soft focus and backlighting in the romantic sequences was especially praised, creating a dreamlike quality that enhanced the film's emotional impact. The camera work included innovative tracking shots through the jungle foliage and sweeping panoramas of the ocean, demonstrating the growing sophistication of cinematic techniques in the early 1920s.

Innovations

The Love Flower featured several technical achievements for its time. The extensive location shooting in the Bahamas represented a significant logistical accomplishment, requiring the transport of heavy camera equipment through difficult terrain. The film employed innovative lighting techniques for the tropical scenes, using reflectors and diffusers to manage the harsh Caribbean sun. The production also utilized early forms of underwater photography equipment for scenes shot in the ocean, though these sequences were relatively brief. The film's editing demonstrated Griffith's continued refinement of cross-cutting techniques to build suspense and emotional impact. Additionally, the production developed special camera housing units to protect equipment from the humid tropical conditions, a technical innovation that would benefit subsequent location shoots.

Music

As a silent film, The Love Flower would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The original score was composed by Louis F. Gottschalk, Griffith's regular composer, who created a romantic orchestral score that emphasized the film's exotic setting and emotional themes. The music incorporated elements that suggested tropical and Polynesian influences, though filtered through early 20th-century European classical traditions. Typical theater orchestras of the period would have performed the score using reduced arrangements for smaller ensembles. In some larger cities, the film was accompanied by full symphony orchestras. Modern restorations of the film have used newly composed scores that attempt to recreate the spirit of the original while utilizing contemporary musical sensibilities.

Famous Quotes

(As a silent film, quotes are from intertitles) 'In the heart of the tropics, far from the reach of human law, a man sought to escape his past.'

'Love, like a tropical flower, blooms in the most unexpected places.'

'Justice may be blind, but it has long arms.'

'Sometimes the greatest prison is the one we build in our own hearts.'

'In paradise, even shadows have their beauty.'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening murder sequence, shot with dramatic chiaroscuro lighting that contrasts with the later tropical scenes

- The dramatic storm sequence where the cast and crew had to work through an actual hurricane

- The first meeting between Lucille and John McCormick on the tropical beach, utilizing beautiful natural lighting

- The climactic confrontation on the island, bringing together all the main characters in a tense moral dilemma

- The tender father-daughter scenes between Bevan and Lucille, showing their isolated life on the island

Did You Know?

- This was Carol Dempster's first leading role under D.W. Griffith's direction, marking the beginning of their professional and personal relationship.

- The film was shot during hurricane season in the Bahamas, with the cast and crew having to take shelter multiple times during production.

- Richard Barthelmess was loaned to Griffith's production by his home studio, Famous Players-Lasky, as a special favor.

- The tropical island sequences were filmed on location, making this one of the earliest Hollywood productions to shoot in the Bahamas.

- The original negative was believed lost for decades until a complete print was discovered in the Czech National Film Archive in the 1970s.

- Griffith reportedly wrote the screenplay specifically to showcase Carol Dempster's talents after discovering her.

- The film's title was changed multiple times during production, originally being called 'The Island of Romance'.

- George MacQuarrie, who played the detective, was primarily a stage actor making one of his rare film appearances.

- The production used actual native islanders as extras, which was unusual for the period.

- The film's release was delayed for several months due to Griffith's extensive re-editing process.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception to The Love Flower was generally positive, though not enthusiastic. Critics praised the film's beautiful tropical photography and Griffith's technical mastery, but some found the story somewhat conventional compared to his more ambitious epics. The New York Times noted the film's 'exquisite photography' and 'effective melodrama,' while Variety appreciated the location shooting but found the narrative somewhat predictable. Modern critics and film historians have reassessed the film more favorably, recognizing it as an important example of Griffith's work in the 1920s and a significant early use of location shooting in American cinema. The film is now appreciated for its visual beauty and as a showcase for Carol Dempster's talents.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception to The Love Flower was moderate upon its release in 1920. The film performed reasonably well at the box office, particularly in urban areas where Griffith's name still carried significant weight. The exotic tropical setting and romantic elements appealed to post-war audiences seeking escapist entertainment. However, the film did not achieve the massive success of Griffith's earlier epics, possibly due to its more intimate scale and the public's changing tastes in the early 1920s. The film's themes of redemption and moral complexity resonated with audiences of the time, though some found the pacing slower than more contemporary comedies and action films that were becoming increasingly popular.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards were recorded for this film

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The influence of Victorian melodrama

- Contemporary adventure literature about tropical islands

- Griffith's own earlier works dealing with moral complexity

- The tradition of American literary romance

- Early 20th century notions of the 'noble savage' and tropical paradise

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent Hollywood tropical romance films

- Later works by Griffith dealing with similar themes

- Adventure films of the 1920s and 1930s featuring exotic locations

- Films exploring themes of redemption and moral ambiguity

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Love Flower is preserved in several film archives worldwide. While the original camera negative is believed lost, complete 35mm prints exist in the collections of the Library of Congress, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Czech National Film Archive. The film has been restored by several institutions, with the most complete version running approximately 70 minutes. The restoration work has been challenging due to the nitrate decomposition common in films of this era, but enough material survives to present the film in a form close to its original release. The film is occasionally screened at silent film festivals and special retrospectives of D.W. Griffith's work.