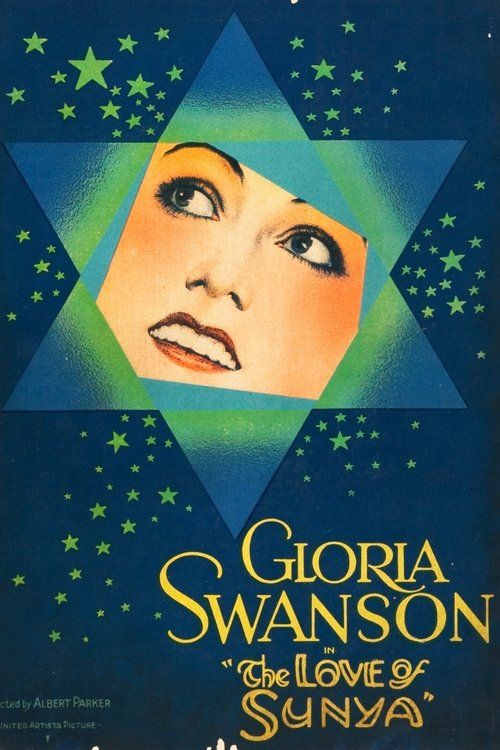

The Love of Sunya

"A woman at the crossroads of destiny... granted a vision of three tomorrows!"

Plot

Sunya Ashling, a young woman facing a crucial decision in her life, is granted mystical visions that show her how different choices will shape her future. The film presents three possible paths her life could take: one as the wife of a wealthy but unloving man, another as the companion of a passionate but unstable artist, and a third as the partner of a simple, honest man who truly loves her. As Sunya witnesses these alternate realities through her prophetic visions, she must navigate the complex web of love, duty, and personal fulfillment. The story explores themes of free will versus destiny as Sunya ultimately must make her own choice without knowing which vision represents her true future. The film culminates in her decision and the revelation of which path she has chosen, leaving audiences to contemplate the nature of choice and consequence.

About the Production

This was Gloria Swanson's first independent production under her own production company. The film was shot during the transitional period between silent and sound cinema, which created additional pressure on the production. Swanson invested significant personal resources into the project, seeing it as a vehicle to demonstrate her dramatic range beyond the flapper roles that had made her famous. The production utilized elaborate sets and costumes to create the different future visions, requiring complex cinematographic techniques for the era.

Historical Background

The Love of Sunya was produced during a pivotal moment in cinema history, arriving in 1927 just as the silent film era was reaching its zenith and about to be transformed by the advent of sound. The film emerged from Hollywood's golden age, when studios were producing hundreds of features annually and stars like Gloria Swanson commanded unprecedented salaries and influence. This period saw the rise of independent production companies as major stars sought greater creative control over their careers. The film's themes of choice and destiny resonated with 1920s audiences who were experiencing rapid social change, technological advancement, and shifting gender roles. The Jazz Age was in full swing, and women were increasingly asserting their independence both on and off screen. The film's release coincided with the publication of influential psychological theories about dreams and the subconscious, making its mystical vision sequences particularly timely and intriguing to contemporary audiences.

Why This Film Matters

The Love of Sunya represents an important transitional work in Gloria Swanson's career and in the broader evolution of American cinema. As Swanson's first independent production, it demonstrated the growing power of star producers in Hollywood and paved the way for other actors to establish their own production companies. The film's innovative use of vision sequences to explore alternate realities anticipated future narrative techniques that would become common in science fiction and fantasy cinema. Its focus on female agency and choice reflected the changing attitudes toward women's roles in society during the 1920s. The movie also serves as a valuable artifact of late silent cinema, showcasing the sophisticated visual storytelling techniques that had been developed before the introduction of sound complicated film production. Though not as well-remembered as some of Swanson's other works, it represents an important step in her artistic development and her transition from flapper icon to serious dramatic actress.

Making Of

The production of 'The Love of Sunya' was marked by Gloria Swanson's determination to establish herself as a serious dramatic actress and producer. She personally selected the project after seeing the stage play and fought to acquire the rights. The filming process was intensive, with Swanson demanding multiple takes to perfect her emotional scenes. Albert Parker, who had previously worked with Swanson on 'Stage Struck' (1925), was chosen as director for his ability to handle dramatic material. The vision sequences required pioneering special effects techniques, including double exposure and matte photography, which were challenging to execute with 1920s technology. The production team worked closely with cinematographer Hal Rosson to create the distinct visual styles for each of Sunya's possible futures. During filming, Swanson clashed with studio executives over budget concerns, but ultimately prevailed in maintaining her artistic vision for the project.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'The Love of Sunya,' handled by Hal Rosson, was particularly notable for its innovative approach to visualizing the mystical vision sequences. Rosson employed multiple exposure techniques to create the ethereal quality of Sunya's prophetic visions, using double and triple exposures to overlay different potential futures. The film utilized distinct visual palettes for each of the three possible futures Sunya witnesses: warm, golden tones for the wealthy marriage; darker, more dramatic lighting for the artistic life; and natural, soft lighting for the simple life of love. Rosson made extensive use of soft focus and diffusion filters to distinguish between reality and vision sequences. The camera work was unusually mobile for a silent film, with several tracking shots that added dynamism to the dramatic scenes. The film also featured elaborate matte paintings and optical effects that were cutting-edge for 1927, creating seamless transitions between different time periods and realities in Sunya's visions.

Innovations

The Love of Sunya featured several technical achievements that were innovative for 1927. The film's most significant technical accomplishment was its sophisticated use of multiple exposure photography to create the vision sequences, requiring precise timing and alignment in an era before modern optical printers. The production team developed new techniques for smoothly transitioning between reality and the mystical visions, using dissolves and superimpositions that were remarkably fluid for the period. The film also employed elaborate matte painting techniques to create the different environments of Sunya's possible futures. The lighting design was particularly advanced, with cinematographer Hal Rosson using different lighting schemes to visually distinguish between the three alternate realities. The makeup and costume departments created distinct looks for each version of Sunya's future, requiring quick changes and careful continuity. These technical innovations, while subtle by modern standards, represented significant achievements in late silent cinema and demonstrated the sophisticated visual storytelling techniques that had been developed by 1927.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Love of Sunya' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The score was likely composed by the theater's musical director or used compiled classical pieces appropriate to the dramatic tone of the film. For the vision sequences, the music would have been particularly important in creating the mystical atmosphere, probably using harp, strings, and woodwinds to evoke the otherworldly quality of Sunya's experiences. The different future visions would have been musically distinguished: grand, orchestral music for the wealthy life; passionate, romantic themes for the artistic path; and simpler, more intimate melodies for the life of true love. No original score recordings survive from the film's initial release, as was typical for silent films. Modern screenings of restored versions often feature newly composed scores or period-appropriate compiled music that attempts to recreate the emotional impact of the original accompaniment.

Famous Quotes

I have seen tomorrow, and it terrifies me.

Which path is real? Which love is true?

In every vision, I am someone else... but in none of them am I completely myself.

The heart wants what it wants, even when the mind shows it another way.

To see the future is a curse when you cannot change it.

Memorable Scenes

- The first vision sequence where Sunya sees herself as a wealthy but unhappy wife, using elaborate multiple exposure techniques to show the gilded cage of her existence

- The emotional confrontation scene where Sunya must choose between her three suitors, showcasing Swanson's dramatic range

- The final vision where Sunya sees the simple life of true love, with soft, naturalistic lighting that contrasts with the other visions

- The climactic decision scene where Sunya rejects the visions and chooses her own path, emphasizing the film's theme of free will

Did You Know?

- This was Gloria Swanson's first film as an independent producer, establishing her own production company to have more creative control over her projects.

- The film was released just months before 'The Jazz Singer' revolutionized cinema with sound, making it one of the last major silent dramas of the era.

- Albert Parker, the director, was originally an actor before transitioning to directing, which gave him unique insight into working with performers.

- The mystical vision sequences were considered technically innovative for their time, using multiple exposure techniques and elaborate optical effects.

- John Boles, who played one of Sunya's suitors, would later become a major star in early sound musicals.

- The film's original title was 'Tomorrow's Love' before being changed to 'The Love of Sunya'.

- Swanson reportedly paid $25,000 for the screen rights to the original play, a substantial sum at the time.

- The film featured one of the first uses of the 'vision sequence' technique that would later become common in cinema.

- Despite Swanson's star power, the film was only moderately successful at the box office, partly due to the impending transition to sound.

- The original negative was believed lost for decades before a partial copy was discovered in European archives.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception to 'The Love of Sunya' was mixed but generally positive regarding Swanson's performance. Critics praised her dramatic range and noted that the film allowed her to move beyond the comedic roles that had made her famous. The New York Times particularly commended Swanson's 'restraint and subtlety' in portraying the complex emotional journey of her character. The vision sequences were widely noted as technically impressive, with Variety calling them 'remarkably well-executed' for the time. However, some critics found the plot contrived and the pacing slow. Modern critics and film historians have reassessed the work as an important example of late silent cinema, with particular appreciation for its innovative visual techniques and Swanson's ambitious attempt to produce meaningful dramatic content. The film is now recognized as a significant, if somewhat overlooked, work in Swanson's filmography and in the broader context of 1920s American cinema.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception to 'The Love of Sunya' was moderate, reflecting both Swanson's star power and the challenges facing dramatic films in an increasingly competitive market. The film attracted Swanson's loyal fanbase, who were curious to see her in a more serious dramatic role and in her first independent production. Many viewers found the vision sequences fascinating and the emotional story compelling, though some audience members accustomed to Swanson's lighter fare found the dramatic tone unexpected. The film's box office performance was respectable but not spectacular, particularly when compared to Swanson's earlier comedies. The timing of the release, just before the sound revolution, may have affected its long-term theatrical run, as audiences were becoming increasingly excited about the new 'talkies.' Despite these challenges, the film developed a cult following among Swanson enthusiasts and silent film aficionados, who appreciated its artistic ambitions and technical innovations.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens

- It's a Wonderful Life (later film with similar themes)

- The works of Sigmund Freud on dreams and the subconscious

- Contemporary spiritualist movements of the 1920s

- German Expressionist cinema's visual style

This Film Influenced

- The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941)

- A Christmas Carol adaptations

- It's a Wonderful Life (1946)

- Sliding Doors (1998)

- Run Lola Run (1998)

- The Family Man (2000)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Love of Sunya was considered a lost film for many decades, with only fragments known to exist. In the 1990s, a nearly complete copy was discovered in European archives, though some scenes remain missing or damaged. The film has been partially restored by film preservationists, with missing scenes reconstructed using production stills and title cards. The surviving elements show varying degrees of deterioration, typical for nitrate films of this era. The restored version, while not complete, provides a good representation of the film's narrative and visual style. The preservation status highlights the fragility of silent film heritage and the importance of international archival cooperation in saving cinematic history.