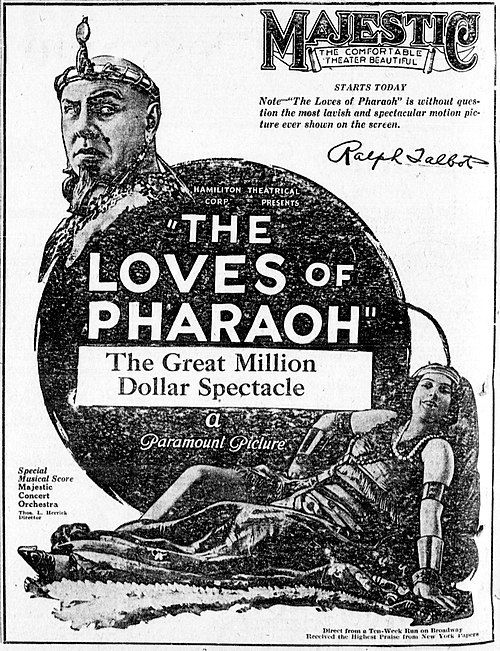

The Loves of Pharaoh

"A Tale of Ancient Love and Royal Intrigue"

Plot

Set in ancient Egypt, the film follows the story of Pharaoh Amenes, who falls deeply in love with Makeda, the beautiful daughter of the Ethiopian King. When the Ethiopian King offers his daughter to secure peace between their nations, Pharaoh Amenes eagerly accepts, hoping to make her his queen. However, complications arise when Ramphis, the son of the Pharaoh, also falls in love with Makeda, creating a dangerous love triangle that threatens both the peace treaty and the royal succession. As political tensions mount and personal passions intensify, the story culminates in a dramatic confrontation that tests the boundaries between duty, love, and power. The film explores themes of sacrifice, betrayal, and the tragic consequences of forbidden love in the ancient world.

About the Production

The film featured extraordinarily elaborate sets designed by Hans Dreier and Ernst Stern, including massive Egyptian palace constructions that required extensive resources. Over 10,000 extras were reportedly used for crowd scenes, making it one of the largest-scale German productions of the early 1920s. The production faced significant challenges due to post-war economic conditions in Germany, including hyperinflation that affected budget calculations. Lubitsch employed innovative camera techniques and lighting to create the ancient Egyptian atmosphere, using special filters and double exposures for certain mystical sequences.

Historical Background

The Loves of Pharaoh was produced during the golden age of Weimar cinema, a period of extraordinary artistic and technical innovation in German filmmaking. The early 1920s in Germany were marked by economic hardship and political instability following World War I, yet paradoxically this environment fostered incredible creativity in the arts. German cinema during this period was characterized by its expressionistic visual style, psychological depth, and technical ambition. The film's production coincided with the height of German Expressionism in cinema, though Lubitsch's approach was more realistic and less stylized than his contemporaries like F.W. Murnau or Fritz Lang. The massive scale of this production reflected Germany's desire to compete with Hollywood on the international market and assert its cultural dominance despite its economic struggles. The film's themes of power, love, and political intrigue resonated with contemporary audiences who were experiencing their own forms of political turmoil and social upheaval. This period also saw the rise of UFA (Universum Film AG) as a major European studio, which produced this film as part of its strategy to create internationally appealing epics that could compete with American imports.

Why This Film Matters

The Loves of Pharaoh represents a crucial transitional work in cinema history, bridging German Expressionism with the more sophisticated visual storytelling that would characterize classical Hollywood cinema. The film demonstrated that German cinema could produce spectacles on par with Hollywood epics while maintaining its distinctive artistic sensibility. Its success helped pave the way for the German exodus of talent to Hollywood in the 1920s, including Lubitsch himself, who would become one of the most influential directors in American cinema history. The film's elaborate production design and visual techniques influenced subsequent historical epics and established new standards for period filmmaking. Its rediscovery and restoration in the late 20th century provided valuable insight into early 1920s German cinema production methods and Lubitsch's directorial evolution. The film also represents an early example of international co-production and distribution strategies that would become standard practice in the film industry. Its themes of cross-cultural romance and political diplomacy remain relevant, and the film serves as an important artifact of how ancient civilizations were portrayed in early cinema.

Making Of

The production of 'The Loves of Pharaoh' was a monumental undertaking that showcased the peak of German cinematic ambition in the early 1920s. Director Ernst Lubitsch, already established as one of Germany's premier filmmakers, pushed the boundaries of what was possible in silent cinema with this epic production. The casting of Emil Jannings as the Pharaoh was a masterstroke, as Jannings was one of the most respected actors of his generation, known for his powerful screen presence and ability to convey complex emotions without dialogue. The production team faced numerous challenges, including the economic instability of post-WWI Germany, which made budgeting difficult due to rampant hyperinflation. Despite these obstacles, the film's sets were among the most elaborate ever constructed in German cinema up to that point, with entire Egyptian palaces and temples built full-scale at the Tempelhof Studios in Berlin. Lubitsch employed innovative camera movements and lighting techniques to create the ancient atmosphere, often using multiple cameras simultaneously to capture the massive crowd scenes. The film's international success was largely due to Lubitsch's sophisticated visual storytelling, which transcended language barriers and helped establish his reputation as a director of international caliber.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Theodor Sparkuhl and Alfred Hansen was groundbreaking for its time, employing innovative techniques to create the ancient Egyptian atmosphere. The filmmakers used special filters and lighting effects to simulate the harsh Egyptian sun and create dramatic shadows that enhanced the film's emotional impact. The camera work featured elaborate tracking shots and movements that were technically challenging for the period, particularly in the massive crowd scenes. The cinematographers employed multiple cameras to capture different angles simultaneously, a technique that was still relatively rare in 1922. The visual style combined realistic period detail with dramatic lighting that emphasized the psychological states of the characters. The film's use of deep focus and careful composition created a sense of depth and scale that enhanced the epic nature of the production. Special photographic techniques were used for certain sequences, including double exposures for mystical elements and innovative matte paintings to extend the massive sets. The cinematography successfully balanced the need for spectacle with intimate character moments, using close-ups strategically to emphasize emotional beats while maintaining the film's epic scale.

Innovations

The Loves of Pharaoh showcased numerous technical innovations that pushed the boundaries of early 1920s filmmaking. The production employed revolutionary set construction techniques, creating massive Egyptian palaces and temples that were among the largest ever built for a film at that time. The film's special effects team developed innovative methods for creating crowd scenes, using careful camera placement and editing techniques to make thousands of extras appear even more numerous. The cinematography featured advanced lighting techniques, including the use of massive reflectors to simulate sunlight and create dramatic shadows. The film also utilized pioneering matte painting techniques to extend sets and create the illusion of even larger spaces. Makeup and costume design innovations were particularly noteworthy, with the team developing new techniques for creating realistic Egyptian royal appearances that held up under the scrutiny of close-up photography. The production also experimented with early forms of color tinting, using different color tints to enhance the emotional impact of various scenes. These technical achievements not only served the film's narrative needs but also contributed to the advancement of film production techniques that would become standard in the industry.

Music

As a silent film, The Loves of Pharaoh was originally accompanied by live musical performances in theaters. The original score was composed by Eduard Künneke, one of Germany's prominent composers of the era, who created a sweeping orchestral score that matched the film's epic scale. The music incorporated exotic elements meant to evoke ancient Egyptian sounds, including unusual instrumentation and modal melodies that differed from conventional Western classical music. For international releases, different theaters would often use their own arrangements or popular classical pieces that fit the mood of various scenes. Modern restorations of the film have featured newly composed scores by contemporary silent film musicians, who have created music that respects the film's historical context while using modern orchestral techniques. These new scores typically emphasize the film's dramatic tension and romantic elements while maintaining the exotic atmosphere appropriate to the Egyptian setting. The original score's sheet music has been preserved and occasionally performed at special screenings, giving modern audiences a sense of how the film was originally experienced.

Famous Quotes

Silent film - no spoken dialogue, but intertitles included: 'Love knows no boundaries, not even those between kingdoms'

The heart of a Pharaoh is both his greatest strength and his most vulnerable weakness'

In the land of the Nile, even the gods themselves must bow to the power of love'

Memorable Scenes

- The grand entrance of the Ethiopian princess into the Egyptian palace, featuring thousands of extras in elaborate costumes and a procession that stretched across the massive set

- The dramatic confrontation scene between the Pharaoh and his son in the throne room, where Emil Jannings delivers a powerful performance through subtle facial expressions and gestures

- The final banquet scene, which featured unprecedented spectacle with its combination of massive crowd scenes, intricate choreography, and dramatic lighting effects

Did You Know?

- This was Ernst Lubitsch's final German film before moving to Hollywood, marking the end of his German period

- Emil Jannings, who played the Pharaoh, would later become the first winner of the Academy Award for Best Actor

- The film was considered lost for decades until a complete print was discovered in the 1970s

- The original German title was 'Das Weib des Pharao' (The Wife of the Pharaoh)

- Over 10,000 extras were used in the massive crowd scenes, an unprecedented number for German cinema at the time

- The elaborate Egyptian sets were so expensive and massive that they were reused in several other German films of the era

- Lubitsch was reportedly dissatisfied with the final cut and felt the American version was superior

- The film featured groundbreaking special effects for its time, including innovative use of miniatures and matte paintings

- A different ending was filmed for the American release to make it more acceptable to American audiences

- The film's success directly led to Lubitsch's recruitment by Hollywood studios

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film for its visual splendor and Lubitsch's masterful direction. German newspapers hailed it as a triumph of national cinema, with particular acclaim for Emil Jannings' powerful performance as the Pharaoh. International critics were equally impressed, noting the film's sophisticated visual storytelling and technical achievements. The New York Times review of 1922 highlighted the film's 'magnificent spectacle' and Lubitsch's 'sure hand at direction.' Modern film historians view The Loves of Pharaoh as a crucial work in Lubitsch's filmography, representing the culmination of his German period before his Hollywood transition. Critics today appreciate the film's ambitious scale and its role in demonstrating the capabilities of silent cinema. The restoration of the film in the 1990s led to renewed critical appreciation, with many noting how Lubitsch's visual storytelling techniques anticipated many conventions of classical Hollywood cinema. Some contemporary critics have pointed out that while the film's spectacle is impressive, its narrative structure and character development show Lubitsch still developing the sophisticated touch that would define his later American films.

What Audiences Thought

The Loves of Pharaoh was a commercial success both in Germany and internationally, drawing large crowds to cinemas throughout 1922 and 1923. German audiences were particularly impressed by the film's nationalistic elements and the demonstration of German technical prowess in creating such a spectacular production. The film's romantic elements and dramatic storyline appealed to mainstream audiences, while its historical setting gave it an air of cultural importance. In international markets, particularly in the United States, the film was marketed as an exotic spectacle and attracted audiences interested in foreign cinema. The film's success helped establish the historical epic as a popular genre in silent cinema. Despite its age, restored versions of the film continue to attract audiences at film festivals and special screenings, with modern viewers often expressing surprise at the sophistication of the filmmaking and the scale of the production. The film's rediscovery has made it a favorite among silent film enthusiasts and cinema historians, who appreciate its role in the development of cinematic language.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards documented, but received critical acclaim at international film festivals

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Cecil B. DeMille's biblical epics

- German Expressionist cinema

- Ancient Egyptian art and mythology

- Shakespearean tragedy

- Opera and theatrical traditions

This Film Influenced

- The Ten Commandments (1923)

- Ben-Hur (1925)

- The Egyptian (1954)

- Cleopatra (1963)

- The Prince of Egypt (1998)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was believed to be lost for decades until a complete nitrate print was discovered in the 1970s at the George Eastman Museum. The film has since been restored by the Munich Film Museum and other archives, with the most complete version running 115 minutes. The restored version features tinted sequences that replicate the original exhibition practices. While some footage may still be missing, the current restoration is considered remarkably complete for a film of its age. The restored version has been released on DVD and Blu-ray by several specialty labels, ensuring its preservation and accessibility for future generations.