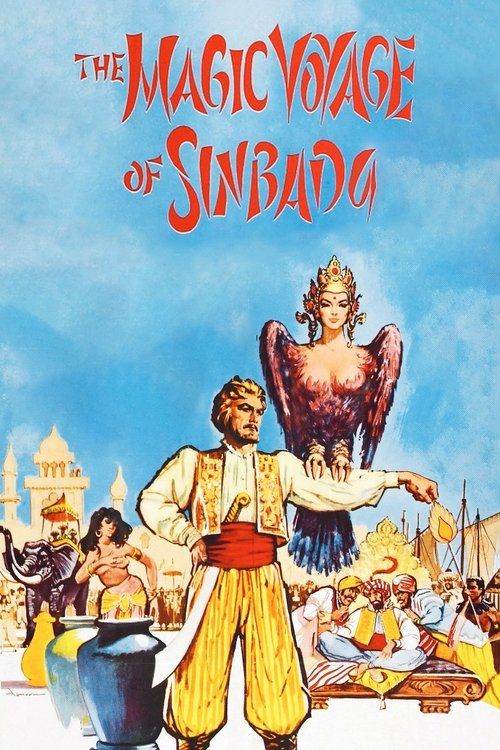

The Magic Voyage of Sinbad

"The Greatest Fantasy Adventure Ever Filmed!"

Plot

In the medieval Russian city of Novgorod, the minstrel Sadko boasts that he can capture the legendary Bird of Happiness for his people, prompting ridicule from the wealthy merchants. Determined to prove himself, Sadko sets sail on an epic voyage across distant lands, encountering mythical creatures, foreign kingdoms, and magical beings along his journey. The Ocean King's daughter, enchanted by Sadko's beautiful singing voice, falls in love with him and aids his quest, though their romance faces challenges from her powerful father. Throughout his adventures, Sadko travels to India, where he seeks exotic treasures, and eventually to the underwater realm of the Ocean King, where he must use his wit and musical talents to survive. The film culminates in a fantastical sequence where Sadko must choose between earthly wealth and true happiness, ultimately learning that the greatest treasure lies not in material riches but in the joy he brings to others through his music.

About the Production

The original Russian version 'Sadko' ran approximately 85 minutes and featured extensive musical sequences from Rimsky-Korsakov's opera. Roger Corman's Filmgroup acquired US rights and created an 8-minute shorter English-dubbed version in 1962, removing much of the operatic content to appeal to American audiences. The dubbing process was typical of Corman's approach to foreign films, with new dialogue written to match existing lip movements. The film was retitled 'The Magic Voyage of Sinbad' to capitalize on the popularity of fantasy adventure films featuring Sinbad, despite the protagonist's actual name being Sadko.

Historical Background

The original 'Sadko' was produced during Stalin's final years in power, a period when Soviet cinema was heavily regulated but also well-funded by the state. The film represented a shift toward more accessible entertainment that still promoted Russian cultural heritage. The choice to adapt a beloved Russian epic and opera was deliberate, emphasizing the richness of Russian culture while creating spectacular entertainment. The 1953 release came just before Stalin's death and the subsequent cultural thaw that would allow more artistic freedom in Soviet cinema. When Roger Corman acquired the film for US distribution in 1962, it was during the height of the Cold War but also a period when American audiences were fascinated with exotic fantasy adventures. Corman's decision to retitle and re-edit the film reflected both commercial considerations and the limited American understanding of Russian culture at the time.

Why This Film Matters

'Sadko' represents a pinnacle of Soviet fantasy filmmaking, showcasing the technical capabilities of Mosfilm Studios while celebrating Russian folklore and musical traditions. The film's blend of opera, epic poetry, and cinematic spectacle created a unique cultural artifact that bridged Russia's artistic heritage with modern filmmaking techniques. The US version's transformation into 'The Magic Voyage of Sinbad' demonstrates how cultural products were adapted for international markets during the Cold War, often losing their specific cultural context in the process. The film remains significant for its influence on subsequent fantasy cinema, both in the Soviet Union and internationally, and for preserving elements of Russian epic storytelling that might otherwise have been lost to modern audiences. Its visual style and special effects techniques influenced generations of fantasy filmmakers, particularly in how they approached combining practical effects with fantastical storytelling.

Making Of

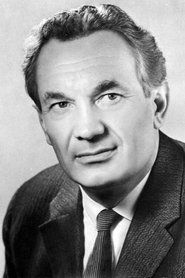

The production of 'Sadko' was a massive undertaking for Mosfilm Studios, requiring the construction of numerous elaborate sets including the Novgorod palace, Indian markets, and the underwater kingdom of the Ocean King. Director Aleksandr Ptushko, who had previously worked on stop-motion animation, employed a combination of techniques including matte paintings, miniatures, and forced perspective to create the fantasy sequences. The underwater scenes were particularly challenging, filmed using large water tanks with special lighting and camera equipment. The musical numbers were recorded first, and the actors had to lip-sync to pre-recorded opera performances. When Roger Corman's Filmgroup acquired the US rights in 1962, they brought in writers to create new English dialogue that would match the existing lip movements while simplifying the story for American audiences. The dubbing process was rushed to capitalize on the fantasy film boom of the early 1960s, resulting in some awkward synchronization and simplified character motivations.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Fyodor Provorov employed innovative techniques for creating fantasy sequences, including elaborate matte paintings that extended the physical sets, multiple exposure techniques for magical effects, and pioneering underwater photography. The visual style emphasized rich, saturated colors that enhanced the fairy-tale quality of the story. The camera work combined sweeping, epic movements for the grand sequences with intimate framing for character moments, creating a sense of scale while maintaining emotional connection. The underwater sequences used specially developed underwater housings for the cameras and innovative lighting techniques to create the ethereal atmosphere of the Ocean King's realm. The film's visual approach influenced subsequent fantasy films, particularly in how it balanced practical effects with cinematographic techniques to create believable fantasy worlds.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical achievements in Soviet cinema, particularly in special effects and fantasy production design. The underwater sequences represented some of the most ambitious underwater filming attempted in Soviet cinema up to that point. The film's use of matte paintings and miniatures to create fantasy environments was groundbreaking for the Soviet film industry. The production team developed new techniques for combining live action with special effects, particularly in scenes involving magical transformations and fantastical creatures. The costume and makeup department created elaborate designs for the fantasy characters that were both visually striking and practical for the actors to wear during the demanding production schedule. These technical innovations influenced subsequent Soviet fantasy films and demonstrated that the Soviet film industry could compete with international productions in the fantasy genre.

Music

The original Russian version featured extensive music from Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov's opera 'Sadko,' with performances by leading Soviet opera singers. The score incorporated traditional Russian folk melodies and classical elements, creating a rich musical tapestry that enhanced the film's epic scope. The US version significantly reduced the musical content, keeping only selected pieces and adding new background music more typical of American fantasy films of the early 1960s. The sound design emphasized the magical elements of the story, with creative use of sound effects for the fantasy creatures and environments. The original Russian soundtrack has been praised for its fidelity to the opera while adapting it effectively to the cinematic medium, while the US version's soundtrack has been criticized for losing much of the cultural specificity of the original.

Famous Quotes

I will bring you the Bird of Happiness, even if I must sail to the ends of the earth!

Music is the true treasure that can never be stolen or spent.

In seeking happiness for others, one often finds it for oneself.

The ocean holds more secrets than all the lands of the earth combined.

A promise made in jest is still a promise that must be kept.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening feast in Novgorod where Sadko makes his boast about capturing the Bird of Happiness, featuring elaborate costumes and set design

- The underwater journey to the Ocean King's palace, with innovative special effects creating a magical underwater world

- Sadko's musical performance that enchants the Ocean King's daughter, showcasing the film's operatic elements

- The sequence in the Indian marketplace, with vibrant colors and exotic props demonstrating the film's scope

- The climactic choice scene where Sadko must decide between earthly treasure and true happiness

Did You Know?

- The film is based on a Russian bylina (epic poem) and Rimsky-Korsakov's 1898 opera 'Sadko'

- Director Aleksandr Ptushko was known as the 'Soviet Walt Disney' for his pioneering work in fantasy films

- The US version removed approximately 8 minutes of content, mostly musical numbers from the opera

- Despite being retitled 'The Magic Voyage of Sinbad,' the character's name is never changed to Sinbad in the dub

- The film features elaborate special effects using matte paintings, miniatures, and stop-motion animation

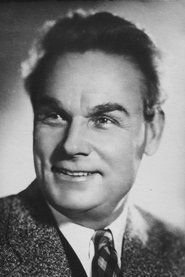

- Sergei Stolyarov, who played Sadko, was one of the Soviet Union's most popular actors of the 1940s-50s

- The underwater sequences were filmed using innovative techniques for the time, including underwater photography

- The film was part of a series of Russian fantasy films that Corman's Filmgroup acquired and re-edited for US audiences

- The costume design was based on historical Russian and Slavic folk art from the medieval period

- The Ocean King's palace set was one of the most expensive and elaborate constructions at Mosfilm Studios that year

What Critics Said

The original 'Sadko' received critical acclaim in the Soviet Union and internationally, praised for its visual spectacle, faithful adaptation of Russian cultural material, and innovative special effects. Soviet critics particularly appreciated the film's celebration of national heritage and its successful integration of opera into cinema. International critics at Venice and Cannes were impressed by the film's visual ambition and technical achievements, though some found the narrative somewhat episodic. The 1962 US version received mixed reviews, with American critics noting the impressive visuals but criticizing the awkward dubbing and simplified storyline. Over time, film historians have come to appreciate both versions for different reasons - the original as a masterpiece of Soviet fantasy cinema, and the US version as an example of cross-cultural film adaptation during the Cold War era.

What Audiences Thought

Soviet audiences embraced 'Sadko' enthusiastically, drawn to its spectacular visuals, familiar cultural references, and beautiful music. The film became one of the most popular releases of 1953 in the USSR, with children particularly responding to its fantasy elements and adventure story. The US version found a modest audience among fantasy film enthusiasts and drive-in moviegoers, though it never achieved the commercial success of other fantasy films of the era like 'The 7th Voyage of Sinbad.' American audiences were often confused by the discrepancy between the title (referencing Sinbad) and the actual story, though many appreciated the film's visual spectacle regardless. Over time, both versions have developed cult followings among fantasy film enthusiasts and Soviet cinema scholars, with the original Russian version being particularly prized by collectors and film historians.

Awards & Recognition

- Venice Film Festival - Silver Lion (1953)

- All-Union Film Festival - First Prize (1954)

- Vasilyev Brothers State Prize of the RSFSR (1953)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Russian bylinas (epic poems)

- Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov's opera 'Sadko'

- Slavic folklore and mythology

- Soviet realist art tradition

- Classical Russian literature

- Medieval Russian chronicles

This Film Influenced

- Ilya Muromets (1956)

- Sampo (1959)

- The Tale of Tsar Saltan (1966)

- Jack Frost (1964)

- The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad (1958)

- Jason and the Argonauts (1963)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The original Russian version 'Sadko' has been preserved in the Gosfilmofond archive and has undergone restoration by Mosfilm. The 1962 US version exists in various film and video formats but has not received official restoration. Both versions are available through specialty distributors and streaming services specializing in classic and international cinema. The Russian version is considered culturally significant and is part of the permanent collection of several major film archives worldwide.