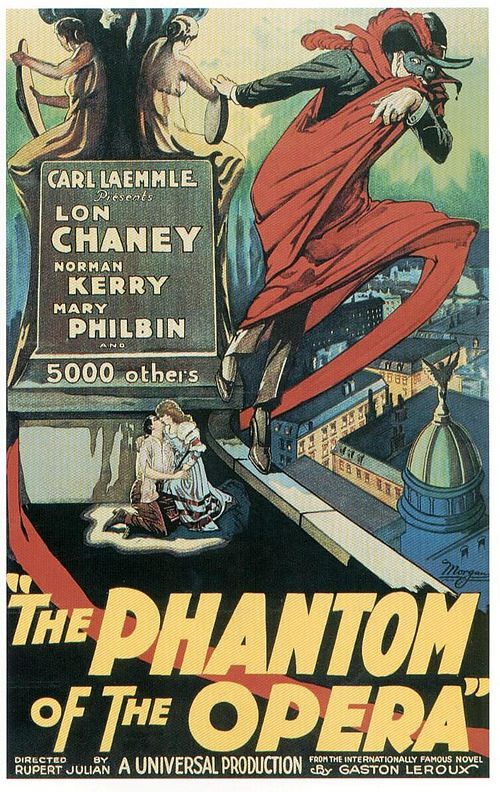

The Phantom of the Opera

"The Greatest of All Horror Dramas! The Phantom Lives!"

Plot

The Phantom of the Opera follows the story of Erik, a disfigured musical genius who lives in the catacombs beneath the Paris Opera House, terrorizing the company and demanding they make Christine Daaé a star. When the young chorus girl Christine becomes the object of Erik's obsession, he begins to systematically eliminate anyone who stands in her way to stardom, including her childhood friend Raoul de Chagny. Erik kidnaps Christine and takes her to his underground lair, where he reveals his true face and demands she choose to stay with him or face dire consequences. The film culminates in a dramatic chase through the streets of Paris as an angry mob pursues the Phantom, ultimately leading to his tragic end. Throughout the narrative, themes of beauty, obsession, and the conflict between artistic genius and societal rejection are explored in this groundbreaking horror masterpiece.

About the Production

The film went through extensive reshoots and multiple directors, with Edward Sedgwick and others contributing after Rupert Julian's initial work. Lon Chaney created his own makeup for the Phantom, which was kept secret from the public until the film's premiere. The famous unmasking scene reportedly caused audience members to faint in theaters. The opera house set was one of the most expensive and elaborate ever built at Universal at that time, costing over $200,000.

Historical Background

The Phantom of the Opera was produced during the golden age of silent cinema, a period when horror was establishing itself as a legitimate genre in American film. The mid-1920s saw the rise of movie palaces and increasingly elaborate productions as studios competed for audiences. Universal Pictures, under Carl Laemmle Jr., was building its reputation for horror films that would later include Dracula and Frankenstein. The film's release coincided with the height of Lon Chaney's fame as 'The Man of a Thousand Faces.' This was also a time of significant technical innovation in cinema, with the industry transitioning toward sound technology, though this film was produced as a silent feature. The 1920s cultural fascination with the grotesque and the mysterious, influenced by post-war anxieties and the growing field of psychoanalysis, provided fertile ground for horror cinema.

Why This Film Matters

The Phantom of the Opera established many conventions of the horror genre that would influence decades of cinema, including the sympathetic monster, the Gothic setting, and the theme of beauty versus monstrosity. Lon Chaney's performance and makeup artistry set new standards for character transformation in film and influenced generations of horror actors and makeup artists. The film helped cement Universal's position as the leading horror studio and paved the way for their classic monster movies of the 1930s. Its success demonstrated that horror could be both artistically ambitious and commercially viable. The film's imagery, particularly the unmasking scene, has become iconic in popular culture and has been referenced and parodied countless times. It also contributed to the enduring popularity of Gaston Leroux's novel, which had been relatively obscure before the film adaptation.

Making Of

The production of The Phantom of the Opera was notoriously troubled, with multiple directors and extensive reshoots. Originally assigned to Rupert Julian, the film underwent significant changes after test screenings, with Edward Sedgwick directing additional scenes and Chaney himself reportedly contributing to direction. The relationship between Julian and Chaney was tense, with the actor often taking creative control. The opera house set was an engineering marvel of its time, featuring working elevators and elaborate underground passages. Chaney's makeup process was grueling, taking hours to apply and causing him considerable discomfort. The film's Technicolor sequences were shot using the early two-strip process, which was expensive and technically challenging. The famous unmasking scene was carefully guarded, with Universal building hype around the mystery of the Phantom's appearance.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Charles Van Enger and Milton Bridenbecker employed innovative techniques for creating atmosphere and suspense. The film makes extensive use of chiaroscuro lighting to create dramatic shadows and enhance the Gothic atmosphere of the opera house. The camera work includes innovative tracking shots through the opera house corridors and dramatic low angles to emphasize the Phantom's menacing presence. The Technicolor Masquerade Ball sequence showcases early color cinematography, with vibrant reds and blues creating a surreal, dreamlike quality. The underground scenes utilize smoke and carefully controlled lighting to create an eerie, claustrophobic environment. The famous unmasking scene uses tight close-ups and dramatic lighting to maximize the shock of the Phantom's revealed face.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations in horror cinema, including elaborate makeup effects that set new standards for character transformation. The opera house set was one of the most ambitious constructions of its time, featuring working elevators, trap doors, and a full-scale replica of the Paris Opera House's grand staircase. The film's use of two-color Technicolor for the Masquerade Ball sequence was technically groundbreaking for a horror film. The falling chandelier sequence involved dangerous practical effects that created a spectacular visual moment. The film also employed innovative camera techniques, including subjective point-of-view shots and dramatic lighting effects that influenced future horror cinematography.

Music

As a silent film, The Phantom of the Opera was originally accompanied by live musical performances in theaters. Universal provided a detailed musical cue sheet for theater orchestras, featuring classical pieces and original compositions. The score incorporated music from Gounod's 'Faust' and other operas that appear in the film's story. For the 1929 sound version, a new musical score was recorded with synchronized sound effects and limited dialogue sequences. Modern restorations have featured new scores by composers such as Carl Davis and the Alloy Orchestra. The original cue sheets emphasized dramatic, romantic music that enhanced the film's Gothic atmosphere and emotional intensity.

Famous Quotes

Feast your eyes! Glut your soul on my accursed ugliness!

I am the Phantom of the Opera!

Christine, you must love me!

If I am the Phantom, it is because man's hatred has made me so!

We are not here to bandy words, but to act!

Memorable Scenes

- The unmasking scene where the Phantom's true face is revealed to Christine, causing her to faint in terror

- The Masquerade Ball sequence filmed in Technicolor, featuring the Phantom in his Red Death costume

- The falling chandelier scene that crashes onto the audience below

- The Phantom's dramatic entrance through the mirror in Christine's dressing room

- The final mob chase through the streets of Paris as the Phantom is pursued by an angry crowd

Did You Know?

- Lon Chaney designed and applied his own makeup for the Phantom, using a combination of cotton, collodion, fish skin, and wire to create the character's distinctive appearance.

- The film was shot in both Technicolor and black and white, with the Masquerade Ball scene originally filmed in two-color Technicolor.

- Chaney's makeup was so extreme and painful that he could only eat through a straw during filming.

- The opera house set was so massive that it took up two entire soundstages at Universal Studios.

- The film was remade with sound in 1929, with some scenes reshot and new dialogue sequences added.

- The famous falling chandelier scene was accomplished using a full-sized chandelier that actually fell during filming.

- Chaney insisted on keeping his Phantom makeup a secret from the public, and Universal's marketing campaign emphasized the mystery of his appearance.

- The film was one of the first to use color sequences in a horror film, with the Bal Masqué scene in Technicolor.

- Mary Philbin reportedly fainted the first time she saw Chaney in full Phantom makeup.

- The underground lake scenes were filmed using smoke and mirrors to create the illusion of water.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film's technical achievements and Chaney's performance, with many calling it the greatest horror film ever made. Variety hailed it as 'a picture that will live forever' and particularly noted Chaney's 'marvelous' performance. Modern critics continue to celebrate the film, with a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on critical consensus. The film is frequently cited as one of the greatest horror films of all time and a landmark of silent cinema. Critics particularly praise Chaney's performance, the elaborate production design, and the film's atmospheric qualities. The 1929 sound version is generally considered inferior to the original silent version, which is now regarded as the definitive presentation of Chaney's work.

What Audiences Thought

The Phantom of the Opera was a tremendous commercial success upon its release, becoming one of Universal's biggest hits of 1925. Audiences were reportedly terrified by Chaney's unmasking scene, with some accounts of viewers fainting in theaters. The film's popularity led to numerous re-releases throughout the silent era and into the sound era. Modern audiences continue to be captivated by the film's power and atmosphere, with it being frequently screened at film festivals and revival houses. The film has developed a cult following among horror enthusiasts and silent film fans, who appreciate its artistry and historical significance. Its enduring popularity has been demonstrated through numerous home video releases and its preservation in the National Film Registry.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards were given for silent films in 1925, though it received several honors from film societies

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Gaston Leroux's 1910 novel 'The Phantom of the Opera'

- German Expressionist cinema (particularly 'The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari')

- Victor Hugo's 'The Hunchback of Notre-Dame'

- Gothic literature tradition

This Film Influenced

- Dracula (1931)

- Frankenstein (1931)

- The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939)

- Psycho (1960)

- The Phantom of the Opera (1943)

- Phantom of the Paradise (1974)

- The Phantom of the Opera (2004)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved and restored multiple times. The original 1925 version exists in various forms, with the most complete restoration being the 1996 Photoplay Productions version that combined elements from different prints. The 1929 sound version also survives, though it is considered inferior to the silent version. In 1998, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress for being 'culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.' Multiple home video releases exist, including DVD and Blu-ray editions with different scores and bonus features.