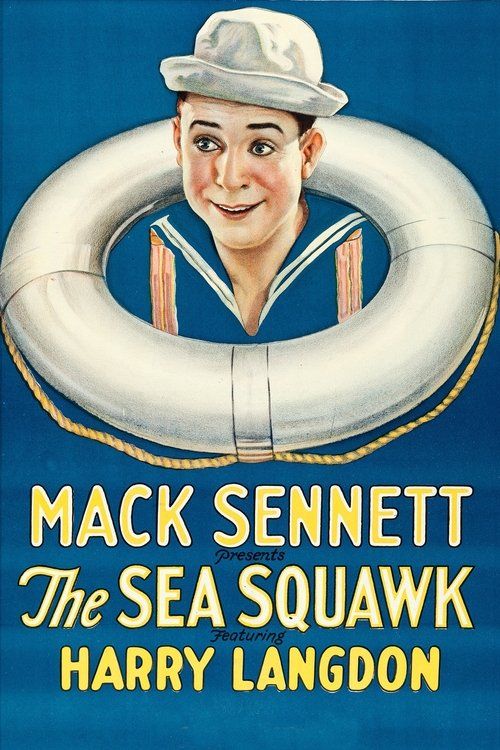

The Sea Squawk

Plot

In this 1925 silent comedy short, a naive Scottish immigrant finds himself in serious trouble aboard the S.S. Cognac cruise ship. Blackie Dawson, a notorious jewel thief, and his accomplice Pearl Blackstone have just stolen a valuable ruby and are being pursued by a determined detective. When the detective begins searching every cabin, Blackie forces the young Scot to swallow the precious gem and remain silent under threat of death. The detective receives assistance from Flora Danube, a sharp-eyed Bulgarian woman who notices everything happening on board. To escape his predicament, the Scottish protagonist disguises himself as a woman, which only draws more unwanted attention. When his disguise is eventually discovered, he must climb for his life to avoid capture and certain death, leading to a series of comedic and dangerous situations aboard the ship.

About the Production

The film was part of Harry Langdon's series of two-reel comedies for Mack Sennett, produced during his breakthrough period. The ship scenes were likely filmed on studio sets with some process photography. The production utilized Sennett's efficient assembly-line approach to comedy filmmaking, typically completing these shorts in just a few days of shooting.

Historical Background

The Sea Squawk was released in 1925, during the golden age of silent comedy and a period of tremendous creativity in American cinema. The film industry was consolidating in Hollywood, with studios like Mack Sennett's establishing efficient production systems for comedy shorts. This was the year that saw the release of landmark films like 'The Gold Rush' (Chaplin) and 'The Freshman' (Harold Lloyd), while comedy stars were becoming some of the biggest celebrities in America. The mid-1920s also saw the rise of feature-length comedies, but two-reel shorts like this remained a crucial part of theater programs. The film's release coincided with Harry Langdon's transition from supporting player to headliner, making it part of an important evolutionary moment in comedy history. The era was characterized by rapid innovation in visual comedy, with performers and directors constantly pushing the boundaries of what could be done without dialogue.

Why This Film Matters

The Sea Squawk represents an important transitional work in Harry Langdon's career and the evolution of American silent comedy. As one of the films that helped establish Langdon's unique 'man-child' persona, it contributed to the diversification of comedy styles beyond the fast-paced slapstick of earlier years. The film exemplifies the sophisticated narrative comedy that was emerging in the mid-1920s, where character-driven humor began to complement physical gags. Its shipboard setting and mistaken identity elements reflect popular comedy tropes of the era while showcasing Langdon's distinctive approach to humor based on innocence and vulnerability. The film is also significant as a product of Mack Sennett's studio system, which had trained and launched numerous comedy stars. As part of Langdon's early starring vehicles, it helped pave the way for his later success in features and contributed to the broader acceptance of character-based comedy in silent film.

Making Of

The Sea Squawk was produced during Harry Langdon's crucial period at Mack Sennett Studios, where he was developing his unique comedic style that would soon make him one of the silent era's major stars. Director Harry Edwards, who had a reputation for working quickly and efficiently, guided Langdon through the physical comedy sequences that would become his trademark. The production utilized Sennett's well-oiled comedy machine, with sets built specifically for rapid shooting and maximum comic effect. The ship setting, while mostly studio-bound, was designed to allow for the kind of physical comedy Langdon excelled at - tight spaces, awkward situations, and the contrast between his innocent character and the criminal elements surrounding him. The film's production timeline was typical for Sennett shorts, with principal photography likely completed in just 2-3 days, followed by rapid editing to meet distribution schedules.

Visual Style

The cinematography in The Sea Squawk was typical of Mack Sennett productions - functional, efficient, and designed to showcase comedy rather than create artistic statements. The camera work by Sennett's regular cinematographers emphasized clarity in the physical comedy sequences, particularly during Langdon's disguise scenes and the climactic chase sequences. The shipboard setting required careful camera placement to create the illusion of being at sea while working within the confines of studio sets. Lighting was bright and even, standard for comedy shorts of the era, ensuring that every facial expression and physical gag was clearly visible to audiences. The cinematography supported the film's narrative without drawing attention to itself, using medium shots for dialogue sequences and wider shots for physical comedy, following the established conventions of silent comedy cinematography.

Innovations

The Sea Squawk employed standard technical practices for comedy shorts of 1925, with no groundbreaking innovations but solid execution of established techniques. The film likely used process photography for some shipboard scenes, projecting background footage to create the illusion of being at sea. The makeup effects for Langdon's disguise as a woman would have been carefully executed to ensure both comedic effect and audience recognition. The film's editing followed the rapid pace typical of Sennett comedies, with quick cuts during action sequences and longer takes for character moments. The technical team would have employed the standard 35mm film format of the era, with the likely use of multiple cameras to capture different angles of the physical comedy sequences. While not technically innovative, the film demonstrates the refined studio system that allowed for efficient production of high-quality comedy shorts.

Music

As a silent film, The Sea Squawk would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its theatrical run. The typical accompaniment would have been a piano player in smaller theaters or a small orchestra in larger venues. The music would have been compiled from various sources, including classical pieces, popular songs of the era, and specially composed mood music. Shipboard scenes would likely have been accompanied by nautical-themed music, while comedy sequences would have used playful, upbeat selections. The score would have followed the established practice of underscoring the emotional content of each scene - romantic music for encounters with women, tense music for the jewel heist elements, and whimsical music for Langdon's innocent moments. No original composed score was created specifically for this short, as was standard practice for two-reel comedies of the period.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, dialogue was conveyed through intertitles and visual expression rather than spoken quotes

Memorable Scenes

- The scene where Langdon's character is forced to swallow the ruby, showcasing his signature expression of innocent terror

- His transformation into a woman, with the resulting confusion and attention it draws

- The climactic sequence where his disguise is discovered and he must climb for his life, combining physical comedy with genuine tension

- The initial confrontation between the jewel thieves and the naive Scottish immigrant

Did You Know?

- This was one of Harry Langdon's early starring vehicles before he became a major comedy star with 'The Strong Man' (1926)

- Director Harry Edwards was a prolific comedy director who worked extensively with both Harry Langdon and Charley Chase

- The film was released during the peak of the silent comedy era, when short subjects were a standard part of theater programs

- Mack Sennett, the producer, was known as 'The King of Comedy' and had discovered Charlie Chaplin, Fatty Arbuckle, and Harry Langdon

- The ship setting was a popular backdrop for comedies of the era, allowing for confined spaces and comedic situations

- Harry Langdon's character in this film showcases his signature 'baby man' persona - an innocent, childlike adult in adult situations

- The film's title 'The Sea Squawk' follows the pattern of catchy, alliterative titles common for comedy shorts of the period

- Eugenia Gilbert, who plays Pearl Blackstone, was a popular actress in comedy shorts throughout the 1920s

- Christian J. Frank, who plays Blackie Dawson, appeared in over 200 films between 1913 and 1952

- The film was released just as Langdon was transitioning from supporting player to comedy star

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception for The Sea Squawk was generally positive within the context of short comedy reviews of the era. Trade publications like Variety and The Moving Picture World typically praised Langdon's emerging style, noting his unique approach to comedy that differed from the more aggressive slapstick of earlier comedians. Critics recognized Langdon's potential as a rising star, with some reviews specifically mentioning his effectiveness in the shipboard setting and his handling of the disguise sequences. Modern film historians and silent comedy scholars view the film as an important example of Langdon's early work, though it's often overshadowed by his later feature successes. The film is appreciated by specialists for showcasing the development of Langdon's signature style and its place in the Sennett comedy canon.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception for The Sea Squawk in 1925 appears to have been favorable, as evidenced by Langdon's continued rise to stardom following its release. Theater audiences of the era were particularly receptive to comedy shorts as part of their regular film programs, and Langdon's innocent, childlike character struck a chord with viewers looking for alternatives to the more aggressive comedy styles of the period. The film's shipboard setting and jewel heist plot provided the kind of familiar yet engaging scenario that audiences expected from comedy shorts. While specific audience data is unavailable for individual shorts of this era, the positive reception contributed to Langdon's growing popularity and his transition to feature films within the next year. Modern audiences who have seen the film through rare screenings or archives generally appreciate it as an example of Langdon's early genius and the sophisticated comedy that was emerging in the mid-1920s.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier Mack Sennett comedies

- Charlie Chaplin's character-based comedy

- Harold Lloyd's everyman hero

- Buster Keaton's physical comedy

- Standard comedy tropes of the era

This Film Influenced

- Later Harry Langdon features

- Character-based comedies of the late 1920s

- Disguise comedies in subsequent eras

- Shipboard comedy films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of The Sea Squawk is uncertain, as with many silent comedy shorts from the 1920s. While some Harry Langdon shorts from this period survive in archives or private collections, others have been lost due to the deterioration of nitrate film and lack of preservation efforts in the early sound era. The film may exist in incomplete form or in archives that have not made it widely accessible. The Library of Congress and other film archives have been working to preserve silent comedies, but many two-reel shorts from this period remain lost or exist only in fragmentary form.