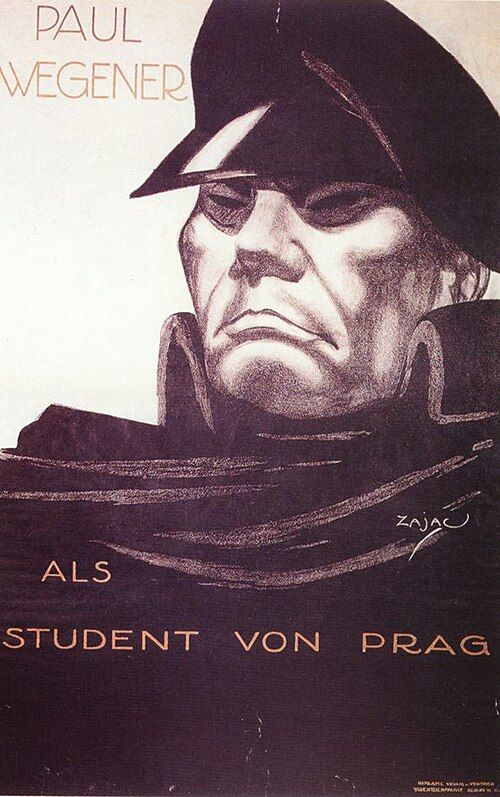

The Student of Prague

"Ein deutscher Künstlerfilm von seltener Schönheit und suggestiver Kraft"

Plot

Set in Prague, Bohemia in 1820, the film follows Balduin, a brilliant but impoverished student who excels at fencing and has fallen deeply in love with Countess Margit, a wealthy noblewoman he saved from drowning. Unable to marry her due to his poverty, Balduin encounters the mysterious Scapinelli, a diabolical figure who offers him a pact: 100,000 gold pieces in exchange for anything in Balduin's room that Scapinelli chooses. After Balduin accepts, Scapinelli claims his reflection, creating a doppelgänger that begins to haunt and undermine him, eventually driving him to madness and tragedy. The film explores themes of duality, Faustian bargains, and the psychological horror of confronting one's darker self.

About the Production

The film was shot at Babelsberg Studios, making it one of the earliest productions at what would become Germany's most famous film studio. The dual exposure technique for the doppelgänger scenes required Paul Wegener to perform against a black background, then the film was rewound and shot again with him in a different position. This primitive but effective special effect was groundbreaking for 1913. The production faced challenges with the complex mirror and double exposure sequences, requiring multiple takes and careful planning.

Historical Background

1913 was a pivotal year in European cinema, occurring just before World War I would dramatically reshape the continent. Germany was experiencing a cultural renaissance, with cinema transitioning from novelty entertainment to artistic expression. The film industry was consolidating, with studios like Deutsche Bioscop establishing permanent facilities. This period saw the emergence of long-form narrative films replacing shorter programs. 'The Student of Prague' emerged during this transitional phase, representing German cinema's artistic ambitions. The film's themes of duality and psychological conflict reflected broader fin de siècle anxieties about modernity, identity, and the human psyche in pre-war Europe. Its production coincided with early Expressionist movements in German art and literature, which would heavily influence cinema in the following decade.

Why This Film Matters

'The Student of Prague' is widely regarded as the first German art film and a foundational work of German Expressionist cinema. It established several conventions that would become staples of German horror and psychological thrillers, including the doppelgänger motif, the Faustian bargain, and the exploration of psychological horror. The film's visual style, with its dramatic use of shadows and innovative camera techniques, directly influenced later Expressionist masterpieces like 'The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari' (1920) and 'Nosferatu' (1922). It demonstrated that cinema could tackle complex psychological themes and literary adaptations, elevating the medium's artistic status. The film's exploration of identity and the divided self became a recurring theme in German cinema of the Weimar period, reflecting the nation's own psychological turmoil during and after World War I.

Making Of

The production of 'The Student of Prague' was groundbreaking for its time. Paul Wegener, who had previous experience in theater, brought a method acting approach to his role as Balduin, insisting on performing his own stunts in the fencing sequences. The doppelgänger effects were achieved through multiple exposure techniques that were revolutionary for 1913. The crew had to paint parts of the set black and use careful lighting to prevent ghosting effects. Director Stellan Rye, though Danish, brought a distinctive visual style that would influence later German Expressionist cinema. The film's cinematographer, Guido Seeber, was a pioneer in special effects and developed new techniques specifically for this production. The cast and crew worked long hours at the newly constructed Babelsberg Studios, which was still in its early development phase.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Guido Seeber was revolutionary for its time, featuring innovative techniques that would influence German cinema for decades. Seeber employed dramatic lighting that prefigured Expressionist cinema, using strong contrasts between light and shadow to create psychological tension. The film's most celebrated technical achievement was the double exposure work used to create Balduin's doppelgänger, which required precise timing and careful preparation. Seeber also utilized unusual camera angles and compositions to enhance the film's psychological atmosphere. The Prague location shots provided authentic Gothic atmosphere, while the studio sets allowed for controlled lighting effects. The cinematography emphasized mirrors and reflections throughout, reinforcing the film's themes of duality and self-confrontation.

Innovations

The film's most significant technical achievement was its pioneering use of double exposure to create the doppelgänger effect, which was revolutionary for 1913. The special effects team developed new techniques for combining multiple images in a single frame, requiring careful masking and precise timing. The film also featured early use of matte photography for certain scenes. The production utilized the newly developed Babelsberg Studios facilities, taking advantage of the modern equipment available there. The film's editing was more sophisticated than typical for the era, with rhythmic cutting to build psychological tension. The makeup effects for the doppelgänger were also notable, creating subtle but effective differences between Balduin and his double. These technical innovations helped establish new possibilities for visual storytelling in cinema.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Student of Prague' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The specific scores used have not been preserved, but typical practice would have involved either a full orchestra in major theaters or a pianist in smaller venues. The music likely drew from classical Romantic composers to match the film's Gothic atmosphere. Modern restorations have been accompanied by newly composed scores, with some versions featuring music by contemporary composers who specialize in silent film accompaniment. The emotional and psychological nature of the film would have required a dynamic musical approach, shifting between romantic themes for the love story and dramatic, dissonant passages for the horror elements.

Famous Quotes

'I will give you 100,000 gold pieces, but in return I will take something from your room - whatever I choose.' - Scapinelli

'Your reflection belongs to me now.' - Scapinelli to Balduin

'Every man has a double in this world.' - Opening intertitle

Memorable Scenes

- The mirror scene where Balduin first confronts his doppelgänger, achieved through revolutionary double exposure techniques that shocked 1913 audiences. The scene where Scapinelli claims Balduin's reflection, creating the pact that drives the entire narrative. The final confrontation between Balduin and his double in the forest, where the student shoots his own reflection and dies from the same wound. The opening sequence where Balduin saves Countess Margit from drowning, establishing their doomed romance. The fencing tournament where Balduin's skills first attract attention, showcasing both his talent and his pride.

Did You Know?

- This is considered the first German art film and a precursor to German Expressionism

- Paul Wegener not only starred but also co-wrote the screenplay and helped develop the story

- The film is loosely based on Edgar Allan Poe's story 'William Wilson' and Faust legends

- It was one of the first films to feature a doppelgänger as a central plot device

- The original negative was lost during World War II, but a restored version exists from a surviving print

- Director Stellan Rye died in World War I just three years after making this film, making it his most famous work

- The film's success led to two remakes: one in 1926 and another in 1935

- It was one of the earliest films to explore psychological horror rather than supernatural horror

- The mirror scene where Balduin first sees his double required innovative use of a glass plate and careful lighting

- The film was initially banned in some countries for its dark themes and psychological intensity

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics in 1913 praised the film's artistic ambitions and technical innovations. German film journals hailed it as a milestone in German cinema, with particular appreciation for Wegener's performance and the groundbreaking special effects. Critics noted its departure from simpler melodramas toward more sophisticated psychological storytelling. Modern critics and film historians recognize it as a crucial precursor to German Expressionism and an important early work in horror cinema. The film is now studied for its pioneering use of double exposure and its influence on subsequent German films. Some modern critics note that while its pacing may seem slow to contemporary audiences, its psychological complexity and visual artistry remain impressive for its era.

What Audiences Thought

The film was a commercial success upon its release in 1913, attracting audiences who were intrigued by its supernatural themes and the novelty of seeing a doppelgänger on screen. German audiences, familiar with the Faust legend and Gothic literature, responded positively to the film's dark themes. The film's success helped establish Paul Wegener as a major star in German cinema. Contemporary audience reports suggest that viewers were particularly impressed by the mirror scenes and the psychological tension throughout the film. The film's popularity led to its export to other European countries and America, where it was received as an example of sophisticated German filmmaking. Modern audiences viewing the restored version often express surprise at the film's technical sophistication and psychological depth for such an early work.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Edgar Allan Poe's 'William Wilson'

- Goethe's 'Faust'

- German Romantic literature

- E.T.A. Hoffmann's stories

- Gothic horror traditions

This Film Influenced

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

- Nosferatu (1922)

- Der Student von Prag (1926 remake)

- The Double Life of Véronique (1991)

- Fight Club (1999)

- Black Swan (2010)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The original camera negative was lost during World War II, but the film survives through various prints that were distributed internationally. A restored version was created by the Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Foundation, combining elements from different surviving prints. The restoration has preserved the film's visual quality and special effects. Some scenes remain incomplete due to damage to the source materials. The film is considered largely intact and is regularly screened at film festivals and special cinema events. Digital restorations have made the film more accessible to modern audiences while preserving its historical significance.