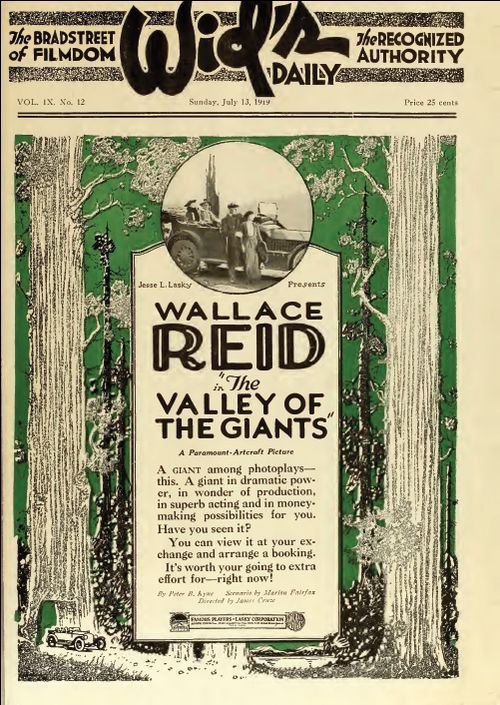

The Valley of the Giants

"A Mighty Drama of the Redwood Country!"

Plot

Bryce Cardigan, a young engineer, returns to his California hometown to help his father's struggling logging company in the redwood forests known as the Valley of the Giants. He plans to build a railroad to transport the massive trees to market, putting him in direct conflict with his rival, Cuthbert, who controls the existing transportation routes. Complications arise when Bryce falls in love with Shirley Sumner, Cuthbert's niece, creating a Romeo-and-Juliet dynamic between the feuding families. The story escalates as both companies resort to sabotage and violence to control the valuable timber resources. Ultimately, Bryce must use his engineering skills and moral integrity to save his family's business while winning the respect of his rivals and the heart of his beloved. The film culminates in a dramatic confrontation that determines the fate of the ancient redwoods and the future of all involved.

About the Production

The film was notable for its on-location shooting in actual redwood forests, which was unusual and challenging for 1919. The production had to transport heavy camera equipment and crew into remote forest locations. The logging sequences required real lumberjacks and authentic equipment, adding to the film's realism. Director James Cruze insisted on using actual fallen redwoods for many scenes to achieve maximum visual impact.

Historical Background

Made in 1919, immediately following World War I, 'The Valley of the Giants' reflected America's post-war industrial boom and the tension between progress and preservation. The film captured the era's fascination with engineering achievements and the conquest of nature through technology, embodied in the railroad construction plot. The logging industry was at its peak during this period, with California's redwoods being harvested at an unprecedented rate. The film also reflected the changing social dynamics of post-war America, with traditional values clashing with modernization. Released during the Spanish Flu pandemic, the film offered escapist entertainment to audiences recovering from the global crisis, while also addressing themes of rebuilding and progress that resonated with the times.

Why This Film Matters

The film holds significant cultural importance as one of the earliest environmental narratives in American cinema, though it ultimately sided with industrial progress. It helped establish the redwood forests as a symbol of American natural grandeur and contributed to early conservation awareness. The movie also cemented Wallace Reid's status as a leading man and helped define the action-drama genre that would become popular throughout the 1920s. Its success demonstrated the commercial viability of location filming and influenced Hollywood's move away from studio-bound productions. The film's portrayal of the American West as a place of both opportunity and conflict contributed to the mythologizing of the frontier experience in popular culture.

Making Of

The production faced significant challenges filming in the remote redwood forests of Northern California. The crew had to build temporary roads to transport camera equipment into the dense forest locations. Wallace Reid performed many of his own stunts, including scenes involving the dangerous logging operations. The film's authenticity was enhanced by the decision to film during actual logging operations, capturing real lumberjacks at work. Director James Cruze was known for his meticulous attention to detail and insisted on using natural lighting whenever possible, which was technically difficult in the deep forest canopy. The romantic scenes between Reid and Darmond were carefully choreographed to contrast with the rugged, masculine world of the loggers, creating a compelling visual and narrative tension throughout the film.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Karl Brown was groundbreaking for its time, featuring sweeping shots of the massive redwood forests that emphasized their scale and majesty. Brown used innovative camera techniques including early forms of crane shots to capture the height of the trees and panoramic views of the logging operations. The film employed natural lighting to dramatic effect, particularly in the deep forest scenes where shafts of sunlight filtering through the canopy created a cathedral-like atmosphere. The action sequences, particularly the logging and railroad construction scenes, used dynamic camera movement that was unusual for 1919. Brown's work on this film helped establish techniques for outdoor cinematography that would influence filmmakers throughout the 1920s.

Innovations

The film was notable for its extensive location photography in challenging forest environments, which required innovative solutions for transporting and operating heavy camera equipment. The production used early forms of camera movement to capture the scale of the redwoods, including techniques that would later evolve into crane shots. The logging sequences required careful coordination between the film crew and actual lumberjacks to ensure safety while capturing authentic action. The railroad construction scenes featured real narrow-gauge trains and authentic engineering equipment, adding to the film's realism. The film's success demonstrated the commercial and artistic potential of location filming, influencing Hollywood's production methods throughout the 1920s.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Valley of the Giants' would have been accompanied by live musical performance in theaters. The original cue sheets suggested orchestral arrangements that emphasized the grandeur of the redwood forests with sweeping string sections, while the action sequences called for more percussive, dramatic scoring. The romantic scenes were typically accompanied by tender piano or violin melodies. Paramount likely provided theaters with compiled scores that included classical pieces and popular songs of the era. The music was designed to enhance the emotional impact of key scenes, particularly the confrontation between the rival logging companies and the romantic moments between the leads.

Famous Quotes

These giants have stood here for two thousand years. Who are we to challenge them?

The railroad will bring progress, Bryce, but at what cost to the valley?

Love knows no boundaries, not even those drawn by competing sawmills.

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic sequence where Wallace Reid's character races against time to complete the railroad bridge before the rival company can destroy it, with actual logging trains and equipment creating a thrilling chase through the redwood forest.

Did You Know?

- Based on the popular 1918 novel 'The Valley of the Giants' by Peter B. Kyne, which was serialized in The Saturday Evening Post

- Wallace Reid was one of the biggest stars of the era, known as 'The Screen's Most Perfect Lover'

- The film was remade in 1938 with Charles Bickford and Jean Parker, but the 1919 version is considered superior by many film historians

- Real lumberjacks were hired as extras and consultants to ensure authenticity in the logging sequences

- The massive redwood trees shown in the film were actual ancient trees, some over 2,000 years old

- Director James Cruze would later direct the epic Western 'The Covered Wagon' (1923), revolutionizing location filming

- The film's success helped establish the 'man vs. nature' genre in Hollywood cinema

- Grace Darmond was a popular actress of the 1910s who retired from films shortly after this production

- The railroad construction sequences were filmed using actual narrow-gauge trains and tracks

- The film was one of the first to use the majestic California redwood forests as a primary setting, showcasing their grandeur to nationwide audiences

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film's spectacular scenery and authentic production values. Variety noted that 'the redwood sequences alone are worth the price of admission' and called it 'a triumph of location photography.' The Moving Picture World highlighted Wallace Reid's performance as 'his most mature and compelling work to date.' Modern critics and film historians have reassessed the film as an important example of early environmental cinema and a showcase of James Cruze's directorial skill. The film is often cited in studies of early American location filming and the development of the action genre. While some modern viewers find the pro-industrial stance dated, the film's technical achievements and Reid's star power continue to earn respect from silent film enthusiasts.

What Audiences Thought

The film was a box office success upon its release, particularly popular in the Western states where logging was a major industry. Audiences were captivated by the spectacular redwood forest sequences, which many had never seen on screen before. Wallace Reid's fan following ensured strong attendance, with many theaters reporting sold-out shows. The romantic subplot appealed to female audiences, while the action and logging sequences attracted male viewers. The film's success led to increased demand for outdoor adventure films and helped establish the commercial viability of location-based productions. Contemporary newspaper accounts indicate that audiences were particularly impressed by the scale of the production and the authentic depiction of logging operations.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Peter B. Kyne's novel

- Contemporary logging industry practices

- Post-WWI industrial expansion narratives

- Western frontier mythology

This Film Influenced

- The Valley of the Giants (1938 remake)

- The Covered Wagon (1923)

- The Big Trail (1930)

- Giant (1956)

- Sometimes a Great Notion (1971)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is partially preserved with some reels missing or damaged. The Library of Congress holds an incomplete copy, and portions have been restored by film archives. Some key sequences survive in good condition, particularly the redwood forest scenes, but other parts remain lost or exist only in fragmentary form.