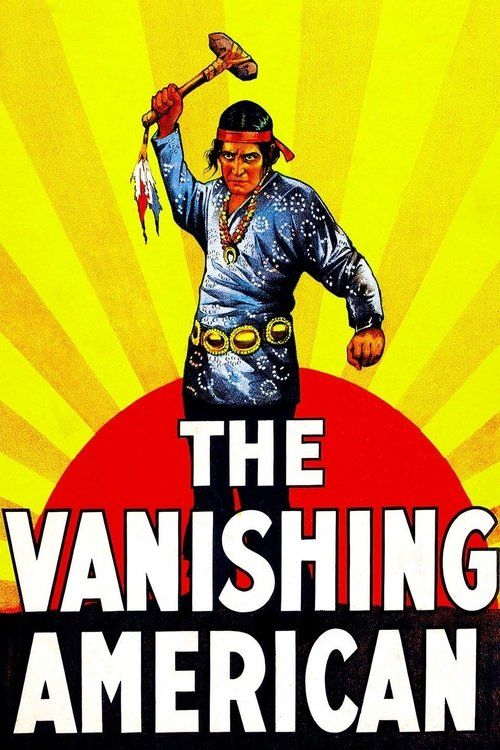

The Vanishing American

"The Epic Story of the Red Man's Last Stand!"

Plot

The Vanishing American tells the story of Nophaie, a young Navajo man played by Richard Dix, who struggles to bridge the gap between his traditional Native American heritage and the encroaching white civilization. After being educated at a government boarding school, Nophaie returns to his reservation to find it mismanaged by the corrupt and cruel Indian agent Booker, who exploits the tribe while claiming to help them. Nophaie falls in love with Marian Warner, a white schoolteacher played by Lois Wilson, who genuinely cares for the Navajo people and opposes Booker's tyrannical rule. When World War I breaks out, Nophaie enlists in the Army, distinguishing himself as a hero in battle, only to return home to find the situation on the reservation has worsened. The film culminates in a dramatic confrontation between Nophaie and Booker, as the Native American protagonist fights to save his people from oppression while grappling with his identity in a changing world.

About the Production

The film was one of the first major Hollywood productions to feature extensive location shooting in the American Southwest. Director George B. Seitz and his crew spent weeks filming on the Navajo reservation, working with actual tribal members as extras. The production faced significant challenges due to the remote locations, including extreme weather conditions and logistical difficulties in transporting equipment. The film's battle scenes were particularly ambitious for their time, involving hundreds of extras and complex choreography. Notably, the production hired several Native Americans as consultants to ensure cultural accuracy, though modern standards would still find many aspects problematic.

Historical Background

The Vanishing American emerged during a period of significant social and cultural change in America. The 1920s saw growing awareness of Native American rights, though often through a paternalistic lens. The film was produced just after the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, which granted U.S. citizenship to all Native Americans born in the country. This historical context gave the film particular relevance, as it addressed themes of cultural assimilation, government exploitation of reservations, and the conflict between traditional values and modernization. The film's release coincided with the height of the silent film era, just before the transition to sound would revolutionize cinema. Its sympathetic portrayal of Native Americans, while still containing many stereotypes of the period, was relatively progressive for its time and reflected growing public interest in the 'vanishing frontier' mythos that dominated American popular culture.

Why This Film Matters

The Vanishing American holds a unique place in cinema history as one of the first major Hollywood productions to attempt a serious examination of Native American issues from their perspective. While still containing many problematic elements by modern standards, including the casting of white actors in Native American roles, the film was groundbreaking in its criticism of government policies toward Native Americans and its humanization of its Native American characters. The film influenced later Westerns by introducing more complex moral ambiguity and social commentary into what had previously been a genre dominated by simple good-versus-evil narratives. Its title itself contributed to the popular 'vanishing race' narrative that dominated American thinking about Native Americans throughout the early 20th century. The film's commercial success proved that audiences would respond to more socially conscious storytelling, paving the way for later films that addressed civil rights and social justice issues.

Making Of

The production of 'The Vanishing American' was groundbreaking in many ways for its time. Director George B. Seitz insisted on extensive location shooting to capture the authentic beauty of the American Southwest, a relatively unusual practice in 1925 when most films were shot on studio backlots. The crew spent nearly two months on location in Monument Valley and the Navajo reservation, living in tents and dealing with harsh desert conditions. The relationship between the film company and the Navajo people was complex - while many tribe members were employed as extras and paid wages, there were also tensions about cultural representation. The film's star, Richard Dix, spent time with the Navajo to prepare for his role, though modern critics note the problematic nature of a white actor playing a Native American character. The battle sequences, depicting both tribal warfare and World War I combat, required elaborate planning and coordination. The production employed several technical innovations, including the use of long lenses to capture sweeping landscape shots that would influence future Western cinematography.

Visual Style

The cinematography by James Wong Howe was revolutionary for its time, particularly in its use of location shooting to capture the majesty of the American Southwest. Howe employed innovative techniques including deep focus photography and extensive use of natural lighting, which gave the film a documentary-like authenticity that was rare in 1925. The sweeping landscape shots of Monument Valley, filmed with newly developed wide-angle lenses, created a sense of epic scale that would influence countless future Westerns. The battle sequences were shot with a dynamic, almost newsreel-like quality that enhanced their impact. Howe's use of contrast and shadow in the interior scenes created a film noir-like atmosphere that was ahead of its time. The cinematography earned special praise from contemporary critics, with Photoplay magazine calling it 'the most beautiful photography of the American West ever captured on film.'

Innovations

The Vanishing American pioneered several technical innovations that would influence future filmmaking. The production was among the first to use extensive location shooting for a narrative feature, demonstrating the dramatic potential of authentic outdoor settings. The film employed innovative camera techniques including crane shots for the sweeping landscape sequences and handheld cameras for the battle scenes, creating a sense of immediacy and realism. The makeup department developed new techniques for creating realistic Native American appearances, though these would later be criticized as part of 'redface' practices. The film's editing, particularly in the action sequences, was unusually dynamic for its time, using rapid cuts and cross-cutting to build tension. The production also utilized new lighting equipment that could be transported to remote locations, allowing for filming during the 'magic hour' to capture the desert landscape at its most beautiful.

Music

As a silent film, The Vanishing American originally featured a musical score composed by Hugo Riesenfeld, one of the era's most prominent film composers. Riesenfeld's score incorporated traditional Native American musical themes alongside classical orchestral arrangements, creating a unique sound that reflected the film's cultural themes. The score was performed live in theaters by house orchestras, with cue sheets provided to ensure consistency across venues. For the film's more dramatic moments, Riesenfeld used leitmotifs to represent different characters and themes, particularly a recurring melody associated with Nophaie's cultural conflict. The original score has been lost, but modern screenings of restored versions often feature newly commissioned scores that attempt to recreate Riesenfeld's blend of Western and Native American musical elements.

Famous Quotes

We are not vanishing. We are changing, but we will not disappear.

The white man's ways are not always better, just different.

You cannot own the land. The land owns us.

In war, I fought for your country. In peace, I must fight for my people.

Education without understanding is just another form of oppression.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing the vast beauty of Monument Valley with the Navajo people living traditionally before white encroachment

- Nophaie's emotional return from boarding school, struggling to reconnect with his family and traditions

- The climactic battle scene where Nophaie leads his people against the corrupt agent's forces

- The World War I trench sequence, starkly contrasting with the earlier tribal warfare

- The final confrontation between Nophaie and Agent Booker on the edge of the canyon

- The romantic scene between Nophaie and Marian Warner by the desert spring, highlighting their cultural differences

Did You Know?

- Based on the 1925 novel 'The Vanishing American' by Zane Grey, which was originally published as a serial in Ladies' Home Journal

- Was one of the first major Hollywood films to feature a Native American protagonist and present a sympathetic view of Native American issues

- Over 500 Navajo tribe members were used as extras during the location filming in Arizona

- The film's original running time was 140 minutes, but it was cut to 110 minutes for theatrical release

- Richard Dix, who played the Native American lead, was actually of Swedish and Scottish descent - a common practice of the era known as 'redface'

- The film sparked controversy upon release for its critical portrayal of the U.S. government's treatment of Native Americans

- A sequel titled 'The Red Frontier' was planned but never produced due to the transition to sound films

- The film's battle sequences were considered groundbreaking for their realism and scale in 1925

- Noah Beery's performance as the villainous agent Booker was so convincing that he received death threats from viewers who couldn't separate the actor from the character

- The film was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry in 1995 for its cultural significance

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception was largely positive, with many reviewers praising the film's ambitious scope and social consciousness. The New York Times called it 'a remarkable achievement in motion picture art' and 'a powerful indictment of government mistreatment of Native Americans.' Variety noted that 'while the film may take some liberties with historical accuracy, its heart is in the right place and its message is timely and important.' Modern critics have a more complex view, acknowledging the film's progressive elements while also criticizing its use of 'redface' casting and perpetuation of certain stereotypes. Film historian Kevin Brownlow has called it 'flawed but essential viewing for anyone interested in the evolution of the Western genre.' The film is now studied in film schools as an example of early social problem cinema and as a reflection of 1920s attitudes toward Native Americans.

What Audiences Thought

The Vanishing American was a significant commercial success upon its release, resonating strongly with audiences of its time. Many viewers were moved by its sympathetic portrayal of Native American characters and its critique of government corruption. The film's battle sequences and romantic subplot also appealed to mainstream moviegoers. Contemporary newspaper accounts report that audiences often gave the film standing ovations, and it played to packed houses in major cities across the country. The film generated considerable discussion about Native American rights, with some audience members reportedly inspired to join reform movements. However, some viewers, particularly in Western states, objected to what they saw as an unpatriotic criticism of the U.S. government. Despite some controversy, the film's box office success demonstrated that audiences were ready for more socially conscious content in their entertainment.

Awards & Recognition

- Photoplay Medal of Honor (1925) - Winner

- National Board of Review - Top Ten Films of 1925

- Academy Film Archive - Selected for preservation (1995)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Covered Wagon (1923)

- The Iron Horse (1924)

- Zane Grey's novels

- D.W. Griffith's Westerns

- Documentary footage of Native American life

- Contemporary newspaper reports about reservation conditions

This Film Influenced

- Stagecoach (1939)

- Fort Apache (1948)

- Broken Arrow (1950)

- Dances with Wolves (1990)

- Smoke Signals (1998)

- The New World (2005)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Vanishing American has been partially preserved, though it exists in an incomplete form. The original 140-minute version is considered lost, with only the 110-minute theatrical cut surviving. The film was preserved by the Museum of Modern Art and the UCLA Film and Television Archive in the 1970s. In 1995, it was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress for being 'culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.' A restored version was released in 2005 with newly created intertitles to replace missing footage. Some scenes, particularly from the original longer cut, exist only as still photographs or written descriptions. The surviving footage shows some deterioration but remains largely viewable, with the color tinting sequences particularly well-preserved.