The White Eagle

Plot

The White Eagle follows Governor V.I. Kachalov, a benevolent administrator of a small Russian province who strives to govern with kindness and fairness toward his subjects. When a local factory erupts in strike action, the governor faces immense pressure from the Tsarist authorities to crush the rebellion. Despite his moral convictions, he ultimately succumbs to political pressure and orders the brutal suppression of the striking workers, resulting in wholesale slaughter. This betrayal of his principles and the people's trust seals his fate when he is assassinated by a determined Bolshevik spy who has infiltrated his household. The film serves as a powerful indictment of the moral compromises made by officials serving an oppressive regime.

About the Production

The film was produced during the early Soviet era when the film industry was still transitioning from revolutionary propaganda to more sophisticated dramatic works. Director Yakov Protazanov, who had returned from emigration in 1923, brought international cinematic techniques to this Soviet production. The production faced challenges in adapting Leonid Andreyev's symbolist play to the screen, requiring significant visual storytelling to convey complex psychological themes without dialogue. The film's production coincided with the Soviet government's increasing control over artistic content, making its critical portrayal of Tsarist authorities politically acceptable while still offering commentary on power and morality.

Historical Background

The White Eagle was produced in 1928, a pivotal year in Soviet history and cinema. This period marked the end of the New Economic Policy (NEP) and the beginning of Stalin's First Five-Year Plan, which would dramatically transform Soviet society and culture. The film industry was undergoing significant changes as the government moved toward greater centralization and control over artistic production. In 1928, the Soviet film community was still benefiting from the creative explosion of the 1920s, which had produced masterpieces by Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and Dovzhenko. However, this artistic freedom was about to be curtailed as the Socialist Realism doctrine would soon be imposed. The film's examination of Tsarist corruption served both as historical commentary and as an allegory for contemporary concerns about bureaucratic power and moral compromise. The timing of its release, just before the Great Break in Soviet cultural policy, made it one of the last films to explore complex moral questions without ideological constraints.

Why This Film Matters

The White Eagle holds an important place in Soviet cinema history as one of the most sophisticated psychological dramas of the silent era. The film represents a bridge between the revolutionary cinema of the early 1920s and the more ideologically rigid productions of the 1930s. Its exploration of individual moral crisis within a political context influenced later Soviet films that attempted to balance personal drama with social commentary. The collaboration between theatre and cinema artists, particularly the involvement of Meyerhold, demonstrated the cross-pollination of artistic disciplines that characterized the Soviet avant-garde. The film's visual language, incorporating elements of both Russian symbolism and constructivism, contributed to the development of a uniquely Soviet cinematic aesthetic. Its critical portrayal of authority figures, while historically set, offered a template for examining power and responsibility that would resonate throughout Soviet cinema. The film also represents an important example of how Soviet cinema dealt with the legacy of pre-revolutionary culture, adapting a symbolist play for revolutionary purposes.

Making Of

The production of 'The White Eagle' represented a significant collaboration between theatre and cinema in the Soviet Union. Director Yakov Protazanov worked closely with Vsevolod Meyerhold, who not only acted in the film but also contributed to the staging of key scenes. The film's visual approach incorporated Meyerhold's revolutionary theatre techniques, particularly his theory of biomechanics, which emphasized precise, mechanical movements to express character and emotion. The strike sequence was filmed using hundreds of extras from Moscow's working class districts, many of whom had actually participated in real labor actions. The production team faced challenges in creating realistic crowd scenes without modern equipment, using innovative camera placement and editing techniques to convey the scale of the workers' uprising. The assassination scene required careful choreography to achieve maximum dramatic impact while adhering to the technical limitations of silent film equipment. The film's score was composed by Vladimir Deshevov, who incorporated revolutionary songs and classical motifs to enhance the emotional narrative.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'The White Eagle' was handled by Yuri Fogelman, who employed sophisticated visual techniques to enhance the film's psychological drama. The camera work incorporated dynamic movement and unusual angles to convey the emotional states of the characters, particularly during the governor's moments of moral crisis. The film used chiaroscuro lighting to create dramatic contrasts between light and shadow, symbolizing the moral ambiguity of the protagonist's position. The strike sequences were filmed with multiple cameras to capture the scale of the workers' uprising, using wide shots to establish the scope of the action and close-ups to emphasize individual emotions. The assassination scene employed rapid editing and dramatic camera angles to create maximum tension and impact. The visual style incorporated elements of both German Expressionism and Soviet constructivism, creating a unique aesthetic that served the film's thematic concerns. The film's visual narrative effectively conveyed complex psychological states without the need for intertitles, demonstrating the maturity of Soviet silent film techniques by the late 1920s.

Innovations

The White Eagle demonstrated several technical innovations for its time, particularly in its approach to crowd scenes and action sequences. The film employed innovative camera movement techniques, including tracking shots that followed characters through complex environments, creating a sense of spatial continuity that was advanced for 1928. The strike sequences used multiple cameras and sophisticated editing to create dynamic action scenes that conveyed both the scale of the uprising and individual human stories within it. The film's special effects, particularly in the assassination scene, used clever editing and camera tricks to create realistic violence without modern technology. The production team developed new techniques for lighting large interior sets, allowing for dramatic visual contrasts that enhanced the psychological drama. The film's use of superimposition and double exposure techniques to represent the governor's internal conflict was particularly innovative for its time. These technical achievements contributed to the film's reputation as one of the most technically sophisticated Soviet productions of the late silent era.

Music

The original score for 'The White Eagle' was composed by Vladimir Deshevov, a prominent Soviet composer known for his modernist approach to film music. The score incorporated elements of Russian folk music, revolutionary songs, and classical motifs to enhance the film's emotional narrative. Deshevov used leitmotifs to represent different characters and themes, particularly associating the governor with tragic minor-key melodies and the striking workers with more triumphant major-key themes. The music for the assassination scene employed dissonant harmonies and dramatic orchestration to heighten the tension and emotional impact. The original score was performed live in theaters during the film's initial run, as was standard practice for silent films. Modern restorations of the film have used Deshevov's original score when possible, or commissioned new music that attempts to capture the spirit of the original composition. The soundtrack represents an important example of early Soviet film music, which sought to create a uniquely Soviet musical language distinct from Western film scoring traditions.

Did You Know?

- Vsevolod Meyerhold, one of the most influential theatre directors of the 20th century, made one of his rare film appearances in this production

- The film was based on Leonid Andreyev's 1908 play 'The Governor', which was controversial in its time for its portrayal of government corruption

- Director Yakov Protazanov had previously worked in France and Germany before returning to the Soviet Union, bringing European cinematic techniques to Soviet cinema

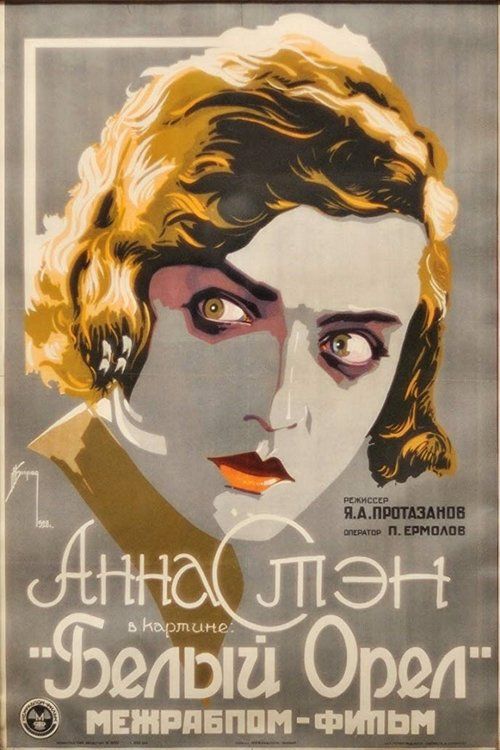

- Anna Sten, who played a leading role, would later be promoted by Samuel Goldwyn as 'the Russian Garbo' and move to Hollywood

- The film's title 'The White Eagle' refers to the double-headed eagle symbol of the Russian Empire, representing the Tsarist authority

- The film was part of a series of Soviet productions in the late 1920s that examined the moral corruption of the pre-revolutionary regime

- The assassination scene was considered particularly shocking for its time, showing the personal consequences of political betrayal

- The film's release came just before the Great Turn in Soviet cultural policy, which would soon restrict artistic freedom significantly

- The original play by Andreyev had been banned in Tsarist Russia, making its film adaptation a statement about Soviet artistic freedom

- The film's visual style incorporated elements of Meyerhold's biomechanics theory of movement, particularly in crowd scenes

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised 'The White Eagle' for its psychological depth and sophisticated visual storytelling. The film was recognized as a significant achievement in adapting complex literary works to the screen, with particular appreciation for Vasiliy Kachalov's powerful performance in the lead role. Critics noted the film's effective use of silent film techniques to convey the internal moral struggle of its protagonist. The collaboration between Protazanov and Meyerhold was highlighted as a successful synthesis of theatrical and cinematic arts. Some critics, however, felt the film was too focused on individual psychology at the expense of broader social themes, reflecting the growing emphasis on collective narratives in Soviet culture. Modern film historians have reevaluated the film as a masterpiece of late Soviet silent cinema, particularly noting its visual sophistication and its nuanced approach to moral and political questions. The film is now recognized as an important transitional work that bridges the experimental cinema of the 1920s with the more conventional narratives of the 1930s.

What Audiences Thought

The White Eagle was well received by Soviet audiences in 1928, who appreciated its dramatic intensity and the performance of Vasily Kachalov, one of the most celebrated actors of the Russian stage. The film's themes of political corruption and moral responsibility resonated with viewers who had lived through the revolutionary period. The assassination scene generated particularly strong reactions from audiences, who saw it as just punishment for betrayal of the people. The film's visual spectacle, particularly the strike sequences, impressed contemporary viewers accustomed to the high production values of Soviet cinema. However, as the political climate changed in the early 1930s, the film's nuanced approach to moral questions became less compatible with official cultural policy. The film gradually disappeared from Soviet screens during the Stalin era, though it remained remembered among cinema enthusiasts. In recent decades, restored versions of the film have been shown at film festivals and retrospectives, where it has been appreciated by modern audiences for its artistic merit and historical significance.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards documented for this film - Soviet film awards were not systematically established until later years

Film Connections

Influenced By

- German Expressionist cinema

- The works of F.W. Murnau

- Soviet montage theory

- Russian Symbolist literature

- Meyerhold's biomechanics theatre theory

- The plays of Leonid Andreyev

This Film Influenced

- Later Soviet psychological dramas

- Films examining bureaucratic corruption

- Soviet historical films of the 1930s

- Post-Soviet films examining revolutionary history