Three's a Crowd

Plot

Harry Langdon plays The Odd Fellow, a lonely tenement worker living in a shack beside a warehouse who yearns for a wife and family like other men. Through his telescope, he spots a pretty girl and sends her a romantic note via carrier pigeon, but the message mistakenly reaches someone else. The girl eventually marries but, facing poverty, leaves her husband during a fierce snowstorm and seeks refuge in Harry's shack, where she gives birth to her child moments later. Harry selflessly works like a slave to support the mother and child, pretending they are his own family, until the husband finds them on Christmas Eve as Harry prepares to play Santa Claus. Oblivious to the heartbreak she's causing, the girl thanks Harry profusely and leaves with her husband, leaving Harry to sit frozen on the doorstep overnight, discovered the next morning stiff as a board except for his eyes, creating a comical yet poignant ending to this silent comedy.

About the Production

This was one of the first films Harry Langdon directed himself after his famous split with collaborators Frank Capra and Harry Edwards. The production was notably troubled, with Langdon struggling to balance directing duties with his performance requirements. The snowstorm sequences were created using artificial snow made from cotton and salt, a common technique in silent film production. The shack set was built on a studio backlot and designed to look authentically dilapidated while still allowing for camera movement and lighting.

Historical Background

1927 was a pivotal year in cinema history, standing at the precipice of the sound revolution with 'The Jazz Singer' set to debut later that year. Silent comedy was still in its golden age, with stars like Chaplin, Keaton, and Lloyd at their peak, but the industry was rapidly changing. Harry Langdon, once considered the fourth great silent comedian alongside these legends, was at a career crossroads. His split with Frank Capra had been highly publicized, and this film represented his attempt to prove his independence as both actor and director. The film's themes of loneliness and economic hardship resonated with audiences of the late 1920s, a period of relative prosperity that would soon give way to the Great Depression. The movie's release came during the transition from short films to feature-length comedies, reflecting the evolving tastes of movie audiences who were increasingly demanding longer, more substantial narratives.

Why This Film Matters

'Three's a Crowd' represents an important but often overlooked chapter in silent comedy history, showcasing Harry Langdon's unique style that differed from his contemporaries. While Chaplin focused on social commentary, Keaton on technical ingenuity, and Lloyd on everyman heroism, Langdon specialized in a more melancholic, childlike innocence that created a distinctive emotional tone. The film's blend of pathos and comedy influenced later performers who sought to balance humor with genuine emotional depth. Its examination of loneliness and the desire for family connection spoke to the urban isolation experienced by many Americans during the 1920s migration to cities. The movie also serves as a fascinating example of the auteur theory in practice, demonstrating how a performer's vision could translate to direction. Though less celebrated than the works of his peers, the film has gained appreciation among silent film enthusiasts for its daring emotional honesty and its place in the broader narrative of comedy's evolution.

Making Of

The production of 'Three's a Crowd' marked a critical juncture in Harry Langdon's career, representing his attempt to prove he could succeed without his former collaborators. Langdon invested much of his own money into the project, convinced that his unique comedic vision could translate to directing. The set design was particularly important to Langdon, who personally oversaw the construction of the shack to ensure it reflected the character's poverty while still being visually interesting. The snowstorm sequences presented significant technical challenges, requiring the crew to develop new methods for creating realistic winter conditions on an indoor set. Cast members reported that Langdon was a demanding director who often required multiple takes to achieve his precise comedic timing, particularly for scenes involving physical comedy. The film's emotional ending was controversial among studio executives who feared it was too bleak for a comedy, but Langdon insisted on keeping it as written.

Visual Style

The cinematography, credited to William Williams, employed techniques characteristic of late silent era filmmaking while serving Langdon's specific comedic needs. The camera work emphasizes Langdon's expressive face through careful lighting and composition, particularly in scenes requiring emotional subtlety. The snowstorm sequences utilized innovative lighting techniques to create the illusion of falling snow while maintaining visibility for the camera. The cramped shack set presented challenges for camera movement, leading to creative solutions involving mirrors and strategically placed windows. The telescope shots were accomplished using special lenses that created a distorted perspective, enhancing the voyeuristic quality of those scenes. The film's visual style balances the artificiality of studio sets with naturalistic lighting in key emotional moments, creating a visual language that supports both comedy and pathos. The Christmas Eve sequence features particularly effective use of shadow and light to create a mood that transitions from festive to melancholic.

Innovations

While not groundbreaking in technical innovation, 'Three's a Crowd' employed several notable techniques for its time. The film's use of multiple camera angles in the confined shack set was more sophisticated than typical for comedies of the era. The snowstorm effects, created using a combination of cotton, salt, and wind machines, were considered quite realistic for 1927. The film also featured some early examples of match cutting between Harry's actions and their emotional consequences, a technique that would become more common in sound films. The telescope shots required special optical equipment to create the desired distortion effect. The frozen ending sequence involved innovative makeup techniques to create the appearance of frostbite while allowing Langdon's eyes to remain mobile for the final gag. The film's editing, particularly in the rapid-fire comedic sequences, demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of rhythm and timing that enhanced the humor.

Music

As a silent film, 'Three's a Crowd' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical score would have been compiled from popular classical pieces and mood music from the era, with specific themes for different characters and situations. The lonely scenes featuring Harry's character would likely have been accompanied by melancholic piano or violin pieces, while the comedic sequences would have used more upbeat, ragtime-inspired music. The snowstorm scenes would have featured dramatic, percussive music to enhance the sense of danger and isolation. Modern restorations of the film have featured newly composed scores by silent film accompanists, typically using piano or small ensemble combinations. These contemporary scores attempt to capture the emotional range of the film while respecting the musical conventions of the silent era. The Christmas Eve sequence, being particularly emotional, would have received special musical attention in both original and modern presentations.

Did You Know?

- This was Harry Langdon's directorial debut, marking a significant turning point in his career after his break with Frank Capra

- The film's original working title was 'The Odd Fellow' before being changed to 'Three's a Crowd'

- The carrier pigeon used in the film was actually trained and performed the scene in one take

- Harry Langdon performed his own stunts, including the frozen scene which required him to remain motionless for extended periods

- The baby in the birth scene was played by twins to accommodate filming schedules

- The film was shot in just three weeks, an unusually short schedule even for the era

- Langdon's characteristic 'baby face' expression was enhanced with special makeup techniques developed specifically for this film

- The Christmas Eve sequence was filmed during July with artificial snow and cooling systems for the actors

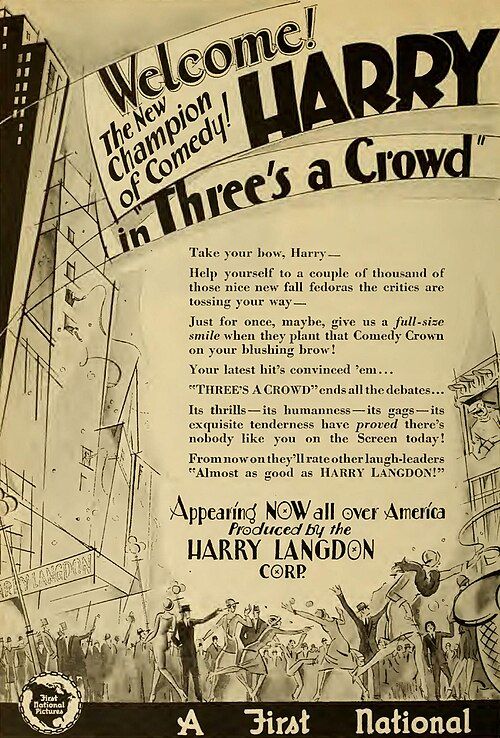

- This film was part of a three-picture deal Langdon had with First National Pictures

- The telescope prop was custom-made and actually functional, allowing Langdon to see the set from a distance

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception was mixed to positive, with reviewers praising Langdon's performance but questioning his directorial abilities. The Variety review noted 'Langdon's trademark sweetness remains intact, but the pacing occasionally suffers under his dual responsibilities.' The New York Times acknowledged the film's emotional power, stating 'Few comedies dare to end on such a bittersweet note, and Langdon should be commended for his courage.' Modern critics have reevaluated the film more favorably, with many considering it an underrated gem that showcases Langdon's unique comedic sensibility. Film historian Kevin Brownlow has written that 'Three's a Crowd' demonstrates 'the full range of Langdon's talent, from slapstick to pathos, in a way his more commercially successful films never quite achieved.' The film's reputation has grown over time, particularly among silent film enthusiasts who appreciate its emotional depth and Langdon's distinctive performance style.

What Audiences Thought

Audience response in 1927 was generally positive, though the film didn't achieve the box office success of Langdon's earlier collaborations with Frank Capra. Moviegoers appreciated Langdon's trademark 'baby face' antics and the film's emotional moments, though some found the ending too bleak for a comedy. The film performed better in urban areas where its themes of loneliness and urban isolation resonated more strongly. In subsequent decades, as silent films became less accessible to general audiences, 'Three's a Crowd' developed a cult following among silent film enthusiasts who discovered it through revivals and film society screenings. Modern audiences who have seen the film through restoration projects have often expressed surprise at its emotional complexity, with many noting that it challenges preconceptions about the simplicity of silent comedy. The film has particularly found appreciation among viewers interested in the more melancholic side of silent comedy, offering a contrast to the more upbeat works of Langdon's contemporaries.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The films of Charlie Chaplin (particularly the blend of comedy and pathos)

- Harold Lloyd's everyman character

- Buster Keaton's deadpan expression

- Earlier Langdon films directed by Frank Capra

- Stage melodramas of the 19th century

- Vaudeville comedy traditions

This Film Influenced

- Later Langdon films as director

- Jacques Tati's character comedies

- Jerry Lewis's more sentimental films

- Jim Carrey's dramatic comedy roles

- The sentimental comedies of the 1930s