Wrong Again

Plot

Stable hands Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy are caring for a valuable thoroughbred racehorse named Blue Boy at their stable when they accidentally overhear two men discussing a $5,000 reward for the return of a stolen masterpiece. The men are actually referring to the famous Gainsborough painting 'The Blue Boy,' but Stan and Ollie mistakenly believe they're talking about their horse. Determined to claim the reward, the duo transport Blue Boy to the wealthy owner's mansion, creating chaos as they attempt to navigate the luxurious home with a full-grown horse. The owner, initially confused by their presence, eventually plays along with their misunderstanding, leading to the famous scene where he instructs them to place 'Blue Boy' on the piano. The comedic climax comes as they struggle to get the horse onto the piano, culminating in the inevitable destruction of both instrument and room, while the boys remain oblivious to the true nature of their error.

About the Production

Wrong Again was produced during the critical transition period from silent films to sound cinema. The film was released in both silent and sound versions, with the sound version featuring a synchronized musical score and sound effects but no dialogue. This dual-release strategy was common during 1928-1929 as studios adapted to the new technology. The film showcases Laurel and Hardy's ability to create visual comedy that transcended the need for spoken dialogue, making it effective in both formats. The production faced the unique challenge of filming with a live horse in interior sets, requiring special accommodations and careful planning for the animal's comfort and safety during the piano sequence.

Historical Background

Wrong Again was released during a pivotal moment in cinema history - the transition from silent films to 'talkies' in 1929. This period, often called the 'sound revolution,' was dramatically reshaping Hollywood as studios rushed to equip theaters for sound and retrain actors, directors, and technicians for the new medium. Many silent film stars saw their careers end during this transition, but comedians like Laurel and Hardy successfully adapted because their humor was primarily visual and didn't rely on dialogue. The film's dual release in both silent and sound versions reflected the industry's uncertainty about audience preferences and the uneven distribution of sound equipment across theaters. 1929 was also the year of the second Academy Awards ceremony and saw the release of the first all-talking picture, 'The Broadway Melody.' The economic boom of the Roaring Twenties was still in full swing when Wrong Again premiered, though the Wall Street Crash of October 1929 would soon alter the entertainment landscape and potentially affect audience tastes. The film's reference to a valuable painting also reflected the growing cultural sophistication of American audiences during this period.

Why This Film Matters

Wrong Again represents a perfect encapsulation of Laurel and Hardy's comedy style at its peak, demonstrating their mastery of visual gags, misunderstanding-based humor, and the classic 'two against the world' dynamic that made them beloved worldwide. The film's premise - a simple misunderstanding escalating into chaos - became a template for countless future comedies across different media. The iconic piano scene has been referenced and homaged in numerous later works, cementing its place in comedy history. As one of the last major silent comedy shorts before the full transition to sound, it serves as an important document of the final flowering of silent comedy techniques. The film also demonstrates how comedy could bridge cultural and language barriers, contributing to Laurel and Hardy's international popularity that made them among the first truly global movie stars. Their gentle, character-driven approach to comedy, exemplified in films like Wrong Again, offered an alternative to the more frenetic style of some contemporaries and influenced generations of comedians who followed.

Making Of

The production of Wrong Again exemplified the efficiency and creativity of Hal Roach Studios during the late 1920s. Director Leo McCarey, who had a keen understanding of Laurel and Hardy's comedic chemistry, encouraged improvisation on set while maintaining tight control over the film's pacing and structure. The piano sequence presented unique technical challenges, requiring the construction of a breakaway prop piano that could safely collapse under the horse's weight while protecting both the animal and the actors. The horse's trainer remained on set throughout filming, using treats and gentle guidance to coax the animal through the required actions. The film was shot quickly, as was typical for Hal Roach two-reelers, with most interior scenes completed in just a few days. The transition to sound technology meant the crew had to be unusually quiet during takes for the sound version, creating an interesting contrast with the chaotic on-screen action. McCarey's direction focused on the duo's physical comedy and timing, allowing their natural rapport to drive the humor while carefully orchestrating the escalating chaos of the mansion scenes.

Visual Style

The cinematography by George Stevens employs the clear, well-lit style typical of Hal Roach productions, ensuring that every visual gag is perfectly visible to the audience. The camera work is straightforward but effective, using medium shots to capture both comedians' reactions and wider shots to establish the scale of the chaos, particularly in the mansion scenes. The filming of the piano sequence required careful camera placement to capture both the horse's movements and the duo's reactions without compromising the comedic timing. Stevens uses deep focus in several scenes to maintain both foreground and background action, allowing viewers to appreciate the full scope of the developing mayhem. The contrast between the humble stable settings and the opulent mansion is enhanced through lighting techniques that emphasize the difference in the boys' environments. The cinematography supports the film's visual comedy by ensuring that every gesture and reaction is clearly visible, a crucial element for silent comedy where facial expressions and body language carry the narrative.

Innovations

Wrong Again demonstrated several technical innovations for its time, particularly in its dual-format release strategy. The film was simultaneously produced in silent and sound versions, requiring careful planning during filming to ensure both formats would work effectively. The synchronized sound version utilized the Vitaphone sound-on-disc system, which was cutting-edge technology in 1929. The piano sequence represented a significant technical achievement in prop construction, requiring the creation of a breakaway piano that could safely collapse under a horse's weight while appearing realistic on camera. The film's production also showcased advances in animal handling techniques for cinema, with the horse's movements carefully choreographed to work within the constraints of indoor filming. The lighting setup for the mansion scenes was particularly sophisticated for the time, using multiple light sources to create the illusion of natural lighting in a studio setting. The film's editing, particularly in the rapid-fire sequence of the piano destruction, demonstrated advanced understanding of comedic timing and rhythm that would influence future comedy filmmaking.

Music

The sound version of Wrong Again featured a synchronized musical score and sound effects but no dialogue, typical of the transitional period of 1928-1929. The music was composed by Leroy Shield, who created many of the memorable themes for Hal Roach productions. Shield's score used light, whimsical melodies that complemented the on-screen action without overwhelming the visual comedy. Sound effects were carefully synchronized to enhance key moments, particularly during the chaotic piano sequence where the sounds of breaking wood, horse movements, and the duo's exclamations added to the humor. The musical themes helped establish the emotional tone of each scene, with playful tunes accompanying the boys' misadventures and more dramatic underscoring during moments of tension. The soundtrack demonstrated how music could enhance silent comedy without the need for spoken dialogue, a technique that would influence comedy scoring for decades to come. The quality of the synchronization was considered above average for the period, reflecting Hal Roach Studios' commitment to embracing new technology while maintaining their comedy standards.

Famous Quotes

These millionaires are peculiar.

Well, here's another nice mess you've gotten me into!

You know, I had a dream like this once.

I've got an idea!

Don't you think you're overdoing it a little?

Memorable Scenes

- The iconic piano sequence where Stan and Ollie attempt to place the horse 'Blue Boy' on a grand piano in the mansion, resulting in the complete destruction of both piano and room while the duo remain oblivious to the absurdity of their actions. The scene escalates from simple misunderstanding to total chaos, showcasing perfect comedic timing and physical comedy as the horse refuses to cooperate, the piano begins to break, and the room descends into mayhem, all while the owner watches with amusement.

Did You Know?

- The film's title 'Wrong Again' became a recurring catchphrase for Laurel and Hardy, often used in their subsequent films when they realized their mistakes.

- The horse used in the film was actually named 'Blue Boy' and was a professional animal actor that appeared in several other films of the era.

- The famous piano scene required building a specially reinforced piano that could support the horse's weight for the brief moments needed for filming.

- This was one of the last Laurel and Hardy shorts released before they transitioned exclusively to sound films.

- The film's premise about the misunderstanding of 'Blue Boy' references Thomas Gainsborough's famous 1779 portrait 'The Blue Boy,' which was (and remains) one of the most valuable paintings in the world.

- Director Leo McCarey would later win two Academy Awards for Best Director and was considered one of the great comedy directors of Hollywood's golden age.

- The mansion scenes were filmed on the same set used for several other Hal Roach productions, with minimal redecoration to save costs.

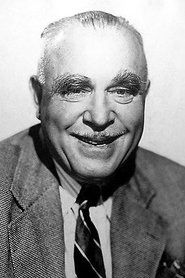

- Harry Bernard, who appears in the film, was a regular character actor in Laurel and Hardy comedies, appearing in over 30 of their films.

- The film's release timing was significant, coming just months before the 1929 stock market crash that would end Hollywood's roaring twenties.

- The synchronized sound version featured music composed by Leroy Shield, who created many of the famous musical themes for Hal Roach comedies.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics in 1929 praised Wrong Again as a fine example of Laurel and Hardy's developing comedy style. The Motion Picture News noted that 'the boys are in top form' and particularly highlighted the piano sequence as 'a masterpiece of comedic construction.' Variety appreciated the film's visual gags and timing, stating that 'Laurel and Hardy prove once again that they need no dialogue to generate laughs.' Modern critics and film historians view Wrong Again as one of the duo's strongest silent shorts, with the British Film Institute describing it as 'a perfectly constructed comedy of errors that showcases the pair's unique chemistry.' Many contemporary reviewers note how the film's humor holds up nearly a century later, with the piano scene frequently cited as one of the most memorable moments in silent comedy. The film is often studied in film schools as an example of perfect comedic pacing and visual storytelling, with particular attention paid to McCarey's direction and the seamless escalation of the central misunderstanding.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1929 embraced Wrong Again enthusiastically, with the film proving popular in both its silent and sound versions. Theater owners reported strong attendance, particularly for showings that paired the short with feature attractions. The film's humor resonated with audiences facing the rapid changes of the late 1920s, offering familiar comedy comfort during uncertain times. Letters to fan magazines of the era frequently mentioned the piano scene as a highlight, with many viewers recalling it as one of the funniest sequences they had seen. The film's success contributed to Laurel and Hardy's growing popularity as they transitioned to full-length features. Modern audiences continue to appreciate the film through revival screenings and home video releases, with comedy enthusiasts often citing it as a favorite among the duo's short films. The timeless nature of the central misunderstanding and the universal appeal of Laurel and Hardy's gentle humor have helped the film maintain its entertainment value across generations.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Classic vaudeville comedy routines

- Mack Sennett's Keystone comedies

- Charlie Chaplin's visual comedy style

- Buster Keaton's technical gags

This Film Influenced

- The Music Box (1932)

- Sons of the Desert (1933)

- Way Out West (1937)

- A Chump at Oxford (1940)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Wrong Again survives in both its silent and sound versions and has been preserved by major film archives including the Library of Congress and the UCLA Film and Television Archive. The film underwent restoration in the 1990s as part of the comprehensive Laurel and Hardy collection preservation project. Both versions are available on various home video releases, including DVD and Blu-ray collections from The Criterion Collection and other specialty distributors. The restoration work has significantly improved the image and sound quality compared to earlier video transfers, making the film accessible to modern audiences while preserving its historical integrity. The film is considered to be in good preservation condition, with no significant loss of footage or degradation that affects viewing comprehension.