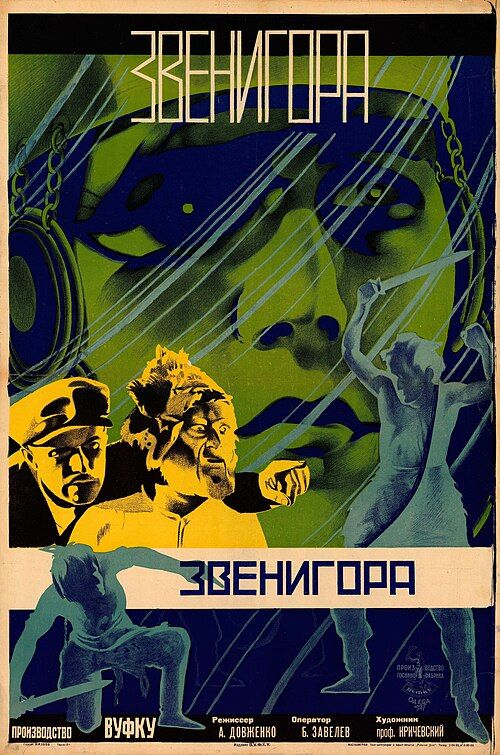

Zvenyhora

Plot

The film follows an elderly grandfather who reveals to his grandson Tymish the secret of a treasure buried in the mountains of Zvenygora, which rightfully belongs to their Ukrainian homeland. Through a series of episodic vignettes spanning centuries of Ukrainian history, the narrative weaves together ancient folklore, Cossack legends, and contemporary Soviet themes. The grandfather serves as a living bridge between Ukraine's rich past and its revolutionary present, guiding viewers through historical battles, folk traditions, and the struggle for liberation. Dovzhenko employs innovative montage techniques to contrast the beauty of Ukrainian landscapes with the brutality of oppression, ultimately building toward a celebration of Ukrainian industrialization and socialist progress. The treasure becomes a powerful metaphor for Ukraine's cultural heritage and revolutionary potential, with the film suggesting that true wealth lies in the land itself and the people's connection to it.

About the Production

The film was shot during a period of relative artistic freedom in Ukrainian cinema before Stalinist cultural restrictions tightened. Dovzhenko faced challenges from Soviet authorities who found the film's Ukrainian nationalism problematic, though it was ultimately approved for release. The production utilized natural lighting extensively and filmed on location across Ukraine to capture authentic landscapes. The treasure sequences required elaborate set construction and special effects for the time. The film's montage style was revolutionary, requiring extensive planning and storyboarding to achieve the complex visual rhythms Dovzhenko envisioned.

Historical Background

The film was produced during the brief period of Ukrainian cultural renaissance in the 1920s, known as the 'Executed Renaissance,' before Stalin's crackdown on national cultures. Ukraine was undergoing rapid industrialization and collectivization, which Dovzhenko sought to celebrate while preserving Ukrainian cultural identity. The film reflects the complex tensions between Soviet internationalism and Ukrainian nationalism that characterized this period. It was created just as Soviet cinema was transitioning from experimental avant-garde to socialist realism, making it one of the last major works of the Soviet avant-garde movement. The film's historical narrative spanning centuries of Ukrainian resistance to foreign domination resonated with contemporary audiences living under Soviet rule. Dovzhenko was working within the VUFKU studio system, which at the time was one of the most progressive and well-funded film studios in Europe, allowing for artistic experimentation that would soon be impossible under Stalinist cultural policies.

Why This Film Matters

'Zvenyhora' represents a watershed moment in both Ukrainian and world cinema, establishing a unique visual language that blended poetic lyricism with political commentary. The film's innovative montage techniques and use of folklore as political allegory influenced generations of filmmakers worldwide. It stands as a crucial document of Ukrainian cultural identity during a period when the nation's autonomy was being systematically eroded. The film's preservation of Ukrainian folklore and historical memory was particularly significant, as many of these traditions were being suppressed by Soviet authorities. Its success helped establish Ukrainian cinema as a distinct artistic voice within the Soviet film industry. The film's visual style, emphasizing the relationship between people and landscape, became a hallmark of Ukrainian cinema. Internationally, it helped demonstrate that Soviet cinema was capable of producing works of artistic merit beyond straightforward propaganda. The film remains a touchstone for discussions about national identity in cinema and the possibilities of political art.

Making Of

The production of 'Zvenyhora' was marked by Dovzhenko's obsessive attention to detail and his revolutionary approach to cinematic language. He spent months researching Ukrainian folklore and history, consulting with historians and folklorists to ensure authenticity. The filming process was challenging due to the remote locations and primitive equipment available in 1920s Ukraine. Dovzhenko insisted on using natural light whenever possible, which meant filming was often dependent on weather conditions. The cast, primarily theater actors, struggled to adapt to the new medium of film, requiring extensive coaching from Dovzhenko on subtlety of expression. The film's complex montage sequences were painstakingly assembled by hand, with Dovzhenko spending weeks in the editing room perfecting the rhythmic flow. There were tensions with VUFKU executives who wanted more overt propaganda, leading to several compromises in the final cut. Despite these challenges, Dovzhenko's artistic vision largely prevailed, resulting in a film that balanced Soviet ideological requirements with Ukrainian cultural specificity.

Visual Style

The cinematography, overseen by Danylo Demutskyi, broke new ground in its poetic use of landscape and innovative camera techniques. The film employs sweeping shots of the Ukrainian steppe that emphasize the intimate connection between people and land. Dynamic camera movements and unusual angles create a sense of mythic timelessness, particularly in the treasure sequences. The use of natural light, especially in outdoor scenes, gives the film a luminous quality that enhances its lyrical atmosphere. Close-ups are used not just for emotional emphasis but as visual metaphors, with faces often framed against natural elements. The film's famous montage sequences create rhythmic visual patterns that suggest the cyclical nature of history. Contrast between light and shadow is used to represent the struggle between oppression and freedom. The cinematography achieves a rare balance between documentary realism and poetic abstraction, making the Ukrainian landscape itself a character in the narrative. Innovative techniques such as superimposition and rapid cutting were employed to create dreamlike sequences that blur the line between reality and folklore.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations that would influence cinema worldwide. Its complex montage sequences, particularly the treasure scenes, represented a breakthrough in editing theory and practice. The film's use of superimposition to create ghostly, dreamlike effects was technically advanced for its time. Dovzhenko developed a unique approach to narrative structure, abandoning linear storytelling in favor of thematic and associative connections. The production achieved remarkable location photography under difficult conditions, utilizing portable equipment to capture remote Ukrainian landscapes. The film's special effects, while simple by modern standards, were innovative for their use of in-camera techniques rather than post-production manipulation. The synchronization of visual rhythms across disparate scenes created a unified aesthetic that influenced theories of film editing. The production also experimented with different film stocks to achieve varying visual textures for different historical periods. These technical innovations were not merely showy but served the film's thematic concerns, particularly its exploration of time and memory.

Music

As a silent film, 'Zvenyhora' was originally accompanied by live musical performances that varied by theater and region. The score typically incorporated Ukrainian folk melodies alongside classical compositions to reflect the film's blend of tradition and modernity. Some screenings featured traditional Ukrainian instruments like the bandura and kobza to enhance the cultural specificity. The musical accompaniment was crucial for conveying emotional tone and narrative rhythm, particularly during the montage sequences. Modern restorations have been paired with newly composed scores that attempt to honor the film's original spirit while utilizing contemporary musical resources. The rhythmic quality of Dovzhenko's editing suggests a strong musical influence in the film's conception, with visual patterns that mirror musical structures. Sound effects were sometimes created live during screenings, particularly for the treasure sequences and battle scenes. The absence of dialogue actually enhances the film's universal appeal, allowing the visual poetry to transcend language barriers. Contemporary screenings often feature live musicians performing original compositions inspired by Ukrainian folk traditions.

Famous Quotes

The treasure is not gold, but the memory of our people, the strength of our land, and the freedom of our spirit - Grandfather's wisdom throughout the film

In every stone of this mountain lies a story, in every wind a song of our ancestors - Opening narration

We have buried our freedom like treasure, waiting for the day when it can be unearthed - Revolutionary dialogue

The past lives in us as we live in the past - Grandfather to Tymish

When the mountains sing, the people listen - Folk wisdom repeated throughout

Not all treasure glitters, and not all freedom comes without sacrifice - Grandfather's warning

The steppe remembers everything, the mountains keep all secrets - Narrator's reflection

To find the treasure, one must first understand the land - Grandfather's lesson to Tymish

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where the grandfather reveals the treasure map, using superimposition to show historical ghosts emerging from the mountains

- The epic montage of Ukrainian history, with rapid cuts showing centuries of resistance and struggle set against the timeless landscape

- The treasure hunt sequence, filmed with dreamlike visual effects that blur reality and folklore

- The industrialization montage, contrasting ancient farming techniques with modern machinery in rhythmic patterns

- The final scene where grandfather and grandson stand atop Zvenyhora mountain, silhouetted against the sunset as the camera pulls back to reveal the vast Ukrainian landscape

- The Cossack battle sequence, using dynamic camera movements and editing to create a sense of mythic heroism

- The folk dance scene, where traditional Ukrainian celebrations become a metaphor for cultural continuity

- The storm sequence, using natural elements to reflect political and social turmoil

Did You Know?

- The film is considered the first installment of Dovzhenko's 'Ukrainian Trilogy,' followed by 'Arsenal' (1929) and 'Earth' (1930)

- Sergei Eisenstein famously praised the film, stating 'As the lights went on, we felt that we had just witnessed a memorable event in the development of the cinema'

- The title 'Zvenyhora' refers to both a mythical mountain and the concept of a ringing or echoing sound, symbolizing the resonance of history

- The film was initially criticized by some Soviet officials for being 'too Ukrainian' in its nationalist themes

- Mykola Nademskyi, who played the grandfather, was a renowned theater actor making one of his first film appearances

- The treasure sequences were influenced by Ukrainian folk tales and legends that Dovzhenko heard from his grandmother

- The film's montage style influenced later filmmakers including Andrei Tarkovsky and Sergei Parajanov

- Original negative was partially damaged during World War II, requiring extensive restoration in the 1970s

- The film was banned in some Western countries during the Cold War for its Soviet propaganda elements

- Dovzhenko considered this his most personal film, saying it contained 'the soul of Ukraine'

What Critics Said

Initial critical reception was mixed, with Soviet critics divided over the film's balance of Ukrainian nationalism and Soviet ideology. Progressive critics praised its innovative visual style and poetic approach to historical material, while more conservative critics found it insufficiently didactic. Sergei Eisenstein's endorsement lent the film considerable prestige within the Soviet film community. Western critics who managed to see the film were impressed by its visual sophistication, though Cold War politics often colored their assessments. Over time, the film's reputation has grown exponentially, with modern critics recognizing it as a masterpiece of silent cinema. Contemporary scholars praise its complex narrative structure and sophisticated use of metaphor. The film is now widely regarded as Dovzhenko's most experimental and personal work, representing the pinnacle of Ukrainian avant-garde cinema. Film historians consistently rank it among the most important films of the 1920s and a crucial development in cinematic language.

What Audiences Thought

Contemporary Ukrainian audiences responded enthusiastically to the film's celebration of their cultural heritage and history, though some found its avant-garde style challenging. The film's blend of familiar folklore with revolutionary themes resonated with viewers navigating the rapid changes of Soviet modernization. In other parts of the Soviet Union, audiences were impressed by its visual beauty though some struggled with its specifically Ukrainian cultural references. The film developed a cult following among intellectuals and artists who appreciated its artistic ambitions. Over time, as the film became more difficult to see due to political restrictions, it gained legendary status among cinephiles. Modern audiences discovering the film through restorations are often struck by its contemporary relevance and visual innovation. Ukrainian audiences today view it as an essential part of their cultural heritage and a testament to artistic resistance. The film continues to be screened at film festivals and retrospectives, where it consistently draws enthusiastic responses from both general audiences and cinema specialists.

Awards & Recognition

- Recognized as one of the 12 best films of all time by the Brussels World's Fair (1958)

- Voted among the greatest films in cinema history by Sight & Sound poll critics (multiple decades)

- Honored at the Venice Film Festival retrospective on Soviet cinema (1972)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Ukrainian folk literature and oral traditions

- The works of Taras Shevchenko (Ukrainian national poet)

- Soviet avant-garde art and constructivism

- German Expressionist cinema

- The theories of montage developed by Soviet filmmakers

- Ukrainian historical chronicles and epic poems

- Symbolist poetry and visual arts

- The landscape painting of Ukrainian artists

- Traditional Ukrainian music and dance

- The revolutionary cinema of Eisenstein and Vertov

This Film Influenced

- Arsenal (1929) - Dovzhenko's own sequel

- Earth (1930) - Final film in Dovzhenko's trilogy

- Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (1964) - Sergei Parajanov

- The Color of Pomegranates (1969) - Sergei Parajanov

- Ivan's Childhood (1962) - Andrei Tarkovsky

- Andrei Rublev (1966) - Andrei Tarkovsky

- The Ascent (1977) - Larisa Shepitko

- Shadows of War (2008) - contemporary Ukrainian cinema

- The Guide (2014) - Oles Sanin

- Winter Sleep (2014) - Nuri Bilge Ceylan (visual influence)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been partially preserved through restoration efforts, though some original footage remains lost. The original negative suffered damage during World War II and subsequent poor storage conditions. Major restoration work was undertaken in the 1970s by Soviet film archives, combining surviving elements from different versions. The Gosfilmofond archive in Russia holds the most complete version, though it's missing some scenes described in contemporary reviews. Additional restoration work was done in the 1990s and 2000s by international film archives, including the British Film Institute and MoMA. The film exists in several versions of varying lengths and quality, reflecting different cuts and restoration attempts. Digital restoration completed in 2015 has made the film more accessible, though some visual quality issues remain due to the condition of source materials. The film is considered at-risk but not lost, with ongoing preservation efforts by Ukrainian and international archives.