20,000 Leagues Under the Sea

"The Greatest Underwater Picture Ever Filmed"

Plot

Captain Nemo, a brilliant but vengeful scientist, has constructed the advanced submarine Nautilus to seek revenge against Charles Denver, the man responsible for the death of Princess Daaker. Nemo's quest has taken him over 20,000 leagues beneath the ocean's surface as he relentlessly pursues Denver. Meanwhile, Denver, consumed by guilt over his actions, has taken the princess's daughter and fled aboard his yacht. The story follows the dramatic confrontation between Nemo and Denver, with the fate of the innocent child hanging in the balance. As the Nautilus navigates the ocean depths, spectacular underwater scenes reveal the wonders and dangers of the marine world, while the human drama of revenge, redemption, and justice unfolds above and below the waves.

About the Production

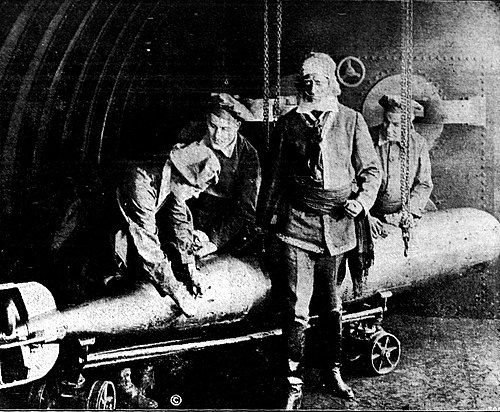

The production was groundbreaking for its time, featuring extensive underwater photography using a specially designed watertight camera housing. The filmmakers built a special underwater chamber that allowed actors to perform beneath the surface while connected to air hoses. The underwater sequences were filmed in the Bahamas, taking advantage of the clear Caribbean waters. The production combined elements from both Jules Verne's '20,000 Leagues Under the Sea' and 'The Mysterious Island' to create a more comprehensive narrative. The submarine Nautilus was constructed as a full-scale prop that could actually submerge for certain shots.

Historical Background

The film was produced during World War I, a time when submarine warfare was becoming a significant military concern, giving the story contemporary relevance. 1916 was also a period of tremendous innovation in cinema, with filmmakers pushing the boundaries of what was technically possible. The silent film era was at its peak, and audiences were hungry for spectacular visual experiences that could only be achieved through the magic of cinema. The film's release coincided with America's growing fascination with technology and exploration, reflecting the progressive spirit of the age. This period also saw the rise of feature-length films as the dominant form of cinematic entertainment, moving away from the short films that had characterized early cinema.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents a landmark achievement in early cinema, particularly in the realm of special effects and location filming. It demonstrated that filmmakers could create believable underwater worlds long before the advent of CGI or advanced diving equipment. The film's success helped establish the adventure/science fiction genre as commercially viable, paving the way for future adaptations of Verne's works and other speculative fiction. It also influenced how submarines and underwater exploration would be portrayed in popular culture for decades to come. The film's technical achievements pushed the boundaries of what was considered possible in filmmaking, inspiring other directors to attempt increasingly ambitious productions.

Making Of

The making of '20,000 Leagues Under the Sea' was a monumental undertaking for 1916 cinema. The production team worked with the Williamson Submarine Film Corporation, pioneers in underwater cinematography, to capture footage that had never been seen before on screen. The underwater camera system used a large brass housing with a glass front, allowing the camera to operate at depths of up to 150 feet. Actors performed underwater while connected to surface air supplies through long hoses, requiring considerable physical endurance. The filming in the Bahamas presented numerous challenges including tropical storms, equipment malfunctions, and the difficulty of coordinating underwater scenes. The production team also built elaborate sets representing the interior of the Nautilus, complete with working machinery and scientific instruments that reflected the Victorian-era fascination with technology and exploration.

Visual Style

The cinematography was revolutionary for its time, particularly the underwater sequences shot using the Williamson Submarine Film Corporation's patented system. The underwater footage was remarkably clear and detailed, showcasing marine life and underwater landscapes with unprecedented clarity. The filmmakers used natural light whenever possible for the underwater scenes, creating a luminous quality that enhanced the otherworldly atmosphere. Above-water sequences employed the standard techniques of the era, including dramatic lighting and careful composition to convey emotion and narrative information. The contrast between the bright underwater scenes and the darker interior shots of the Nautilus created visual variety and helped establish the film's distinctive atmosphere.

Innovations

The film's most significant technical achievement was its extensive underwater photography, accomplished using innovative camera housings and filming techniques. The production team developed methods to keep cameras dry while capturing clear images underwater, a breakthrough that would influence underwater cinematography for decades. The creation of a functioning submarine prop that could actually submerge was another major technical accomplishment. The film also pioneered the use of location shooting for underwater scenes, moving away from the studio-bound productions that dominated the era. These achievements demonstrated that filmmakers could successfully overcome technical barriers to bring imaginative visions to the screen.

Music

As a silent film, it would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical score would have been performed by a theater organist or small orchestra, using popular classical pieces and original compositions appropriate to the on-screen action. No original composed score survives, but modern restorations have been accompanied by newly commissioned scores that attempt to capture the spirit of the film's adventure and wonder. The music would have emphasized the dramatic moments, particularly during the underwater sequences and confrontations between characters.

Famous Quotes

The sea holds secrets that man has yet to discover

Revenge is a dish best served from the depths

In this metal vessel, I am master of all I survey

The ocean knows no boundaries, nor does my vengeance

Memorable Scenes

- The first underwater sequence revealing the Nautilus gliding through crystal-clear waters with marine life swimming past

- The dramatic confrontation between Captain Nemo and Charles Denver aboard the yacht

- The rescue of the child from the sinking vessel during a storm

- The exploration of the underwater ruins showing the lost civilization

- The final battle between submarines beneath the waves

Did You Know?

- This was the first feature-length film to have extensive underwater photography

- The underwater sequences were filmed using a revolutionary underwater camera system designed by the Williamson Submarine Film Corporation

- The film combined plots from two Jules Verne novels: '20,000 Leagues Under the Sea' and 'The Mysterious Island'

- Actors had to hold their breath for underwater scenes as scuba gear had not been invented yet

- The film was considered lost for decades before a copy was discovered and preserved

- Director Stuart Paton was primarily known for action and adventure films during the silent era

- The production cost was unusually high for 1916 due to the innovative filming techniques

- The Nautilus submarine was one of the most elaborate film props of its time

- The film's success helped establish Universal as a major player in feature film production

- Some underwater scenes were filmed in a large tank built specifically for the production

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film's groundbreaking underwater sequences, with many reviews specifically highlighting the novelty and technical achievement of the submerged photography. The Motion Picture News called it 'a marvel of photographic skill' while Variety noted that 'the underwater scenes alone are worth the price of admission.' Modern critics and film historians recognize the film as an important technical milestone in cinema history, though some note that the narrative structure is somewhat disjointed due to the combination of two Verne novels. The film is now appreciated as a pioneering work that demonstrated the artistic and commercial potential of location filming and special effects in the silent era.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1916 were thrilled by the film's underwater sequences, which offered a glimpse into a world few had ever seen. The film was a commercial success, particularly in urban areas where audiences were hungry for spectacular entertainment. The combination of adventure, mystery, and technical innovation proved to be a winning formula with moviegoers of the time. Modern audiences who have seen the restored version often express surprise at the sophistication of the underwater photography for such an early film, though the pacing and storytelling techniques reflect the conventions of silent-era cinema.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Jules Verne's '20,000 Leagues Under the Sea' (1870)

- Jules Verne's 'The Mysterious Island' (1874)

- Contemporary submarine warfare developments

- Victorian-era adventure literature

This Film Influenced

- 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954)

- The Abyss (1989)

- Das Boot (1981)

- Underwater adventure films of subsequent decades

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered lost for many years but a complete print was discovered and has been preserved by major film archives. The Library of Congress maintains a copy in their collection, and the film has been restored and released on home video. The restoration work has preserved the groundbreaking underwater sequences that make this film historically significant.