A Woman of Paris: A Drama of Fate

"A Drama of Fate"

Plot

Marie St. Clair and Jean Millet, a young couple from a small French town, plan to elope to Paris. When Jean's father dies unexpectedly, he cannot join Marie at the train station, leading her to believe she has been abandoned. Heartbroken, Marie travels to Paris alone and eventually becomes the mistress of wealthy socialite Pierre Revel, embracing a life of luxury and sophistication. A year later, Marie encounters Jean by chance in Paris, where he has become a struggling artist. Their reunion forces Marie to confront her feelings and choose between her glamorous but empty existence with Pierre and the genuine love she once shared with Jean, ultimately leading to tragic consequences as past and present collide.

About the Production

Chaplin's first film for United Artists, created as a dramatic showcase for Edna Purviance. The film was shot in complete secrecy with Chaplin using the pseudonym 'The Man in the Hat' during production to avoid media attention. Chaplin deliberately did not appear in the film, wanting to prove he could direct serious drama. The production took approximately six months to complete, unusually long for the era.

Historical Background

Released in 1923, 'A Woman of Paris' emerged during Hollywood's transition to more sophisticated storytelling and the rise of the 'flapper' era. The film reflected post-WWI disillusionment and changing social mores regarding relationships and morality. This was a period when American cinema was increasingly competing with European art films, and Chaplin's attempt to create a European-style drama represented Hollywood's artistic ambitions. The early 1920s also saw the establishment of United Artists, the studio co-founded by Chaplin, and this film was crucial in demonstrating his ability to produce serious artistic work outside the comedy genre that made him famous.

Why This Film Matters

Though initially a commercial failure, 'A Woman of Paris' has been reassessed as a groundbreaking work that influenced generations of filmmakers. Its realistic approach to adult themes and sophisticated narrative structure helped pave the way for more serious dramatic cinema in Hollywood. The film's influence can be seen in the works of directors like Ernst Lubitsch and Josef von Sternberg. Chaplin's use of subtle visual storytelling and emotional nuance demonstrated the artistic potential of cinema beyond comedy. The film's re-release in 1976 with Chaplin's original score brought renewed appreciation for its artistic merits and its place in Chaplin's evolution as a filmmaker.

Making Of

Chaplin approached 'A Woman of Paris' with revolutionary seriousness, abandoning comedy completely to create a sophisticated European-style drama. He worked meticulously with Purviance for months to prepare her for the dramatic role, conducting extensive rehearsals. The production was marked by Chaplin's obsessive attention to detail, requiring countless retakes for emotional scenes. Chaplin's relationship with Purviance had ended romantically by this time, but he remained deeply invested in her career success. The film's realistic approach to adult themes and relationships was groundbreaking for Hollywood cinema. Chaplin's decision not to appear in the film was a bold artistic statement, though it ultimately confused audiences who expected to see the Little Tramp. The production process was unusually long for the era, with Chaplin taking six months to perfect the film.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Rollie Totheroh and Henry Kotani employed sophisticated lighting techniques and camera movements unusual for the time. Chaplin used subtle visual metaphors and symbolic imagery throughout the film, particularly in scenes contrasting Marie's simple beginnings with her luxurious Paris life. The film featured innovative use of shadows and lighting to create emotional atmosphere, especially in the dramatic confrontation scenes. The camera work was more restrained and observational than typical Hollywood films of the era, reflecting European influences. Chaplin employed careful composition and framing to enhance the emotional impact of key scenes, particularly the final sequences.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations in dramatic filmmaking, including sophisticated lighting techniques to convey emotional states. Chaplin's use of camera movement and positioning was more advanced than typical Hollywood productions of the era. The film's editing style, particularly in the montage sequences showing Marie's life in Paris, was innovative for its time. Chaplin employed subtle special effects and double exposure techniques in dream sequences that were technically impressive for 1923. The production design and art direction created realistic European settings that were unusually detailed for American films of the period.

Music

The original film was released as a silent picture with musical accompaniment provided by theater orchestras. In 1976, Chaplin composed and recorded a new musical score specifically for the film's re-release. This score was one of the last works Chaplin completed before his death and demonstrated his lifelong passion for music composition. The 1976 score features sophisticated orchestral arrangements that enhance the film's emotional depth and dramatic tension. Chaplin's use of leitmotifs for different characters and situations adds a new layer of meaning to the visual storytelling.

Famous Quotes

Fate is a strange thing. It can bring two people together, and then tear them apart.

In Paris, one must choose between love and luxury.

The past has a way of catching up with us, no matter how fast we run.

Sometimes the greatest tragedy is not losing love, but finding it too late.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening train station sequence where Marie waits for Jean and their heartbreaking separation

- The lavish Paris party scenes contrasting Marie's new life with her humble beginnings

- The chance encounter between Marie and Jean on the Paris streets

- The emotional confrontation in Marie's apartment where she must choose between her two lives

- The final tragic sequence that brings the story to its powerful conclusion

Did You Know?

- This was Charlie Chaplin's first full-length dramatic film and the only one he directed without appearing in it during the silent era

- Chaplin originally intended this as a star vehicle for Edna Purviance, his frequent collaborator and former romantic partner

- The film was a commercial failure upon release, leading Chaplin to withdraw it from circulation for decades

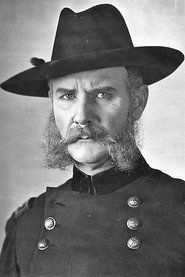

- Adolphe Menjou received his first major role as Pierre Revel, which helped establish his career as a sophisticated leading man

- Chaplin re-released the film in 1976 with a new musical score he composed himself

- The film's failure led Chaplin to return to comedy with his next film, 'The Gold Rush'

- Marlon Brando cited this film as one of his favorites and an influence on his acting style

- Chaplin burned many of the outtakes and unused footage, believing they would never be valuable

- The film's realistic portrayal of relationships was considered controversial for its time

- Chaplin used the pseudonym 'The Man in the Hat' during production to avoid press attention

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics were divided, with many praising the film's artistic ambition while others were confused by Chaplin's departure from comedy. The New York Times called it 'a remarkable achievement in screen artistry,' while Variety noted that 'audiences don't want Chaplin without comedy.' Modern critics have reevaluated the film much more favorably, with many now considering it ahead of its time. Critics today praise its sophisticated visual style, emotional depth, and influence on cinematic language. The film is now recognized as an important transitional work in Chaplin's career and a significant achievement in silent dramatic cinema.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception was overwhelmingly negative, as viewers expecting another Chaplin comedy were disappointed by the serious drama. Many theaters reported walkouts and poor attendance. The film's failure was so complete that Chaplin withdrew it from circulation for decades, only allowing it to be shown in retrospectives. However, when Chaplin re-released the film in 1976 with his new musical score, audiences and critics had a much more positive response, finally appreciating its artistic merits. Modern audiences, viewing it in the context of Chaplin's complete filmography, generally regard it as an impressive dramatic achievement.

Awards & Recognition

- None at the time of release

Film Connections

Influenced By

- European art films of the 1920s

- German Expressionism

- French literary realism

- Victorian melodrama

- Henrik Ibsen's plays

This Film Influenced

- The Joyless Street (1925)

- Pandora's Box (1929)

- City Lights (1931)

- Modern Times (1936)

- The Great Dictator (1940)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is well-preserved with complete copies existing in several film archives. The original negative is held by the Chaplin estate. The film was restored in the 1970s for Chaplin's re-release and again in the 2000s for DVD and Blu-ray releases. The 1976 version with Chaplin's musical score is considered the definitive presentation.