Angel and the Badman

"A GUNMAN'S SOUL... AND A WOMAN'S LOVE!"

Plot

Notorious gunfighter Quirt Evans is wounded when his horse collapses near a Quaker family's homestead. The family, despite warnings from neighbors about his dangerous reputation, takes him in to recover. During his convalescence, Quirt becomes drawn to the family's peaceful lifestyle and their beautiful daughter Penelope, who represents a life of non-violence and faith that challenges his violent ways. As romance blossoms between Quirt and Penelope, he begins to question his outlaw existence, but his past catches up with him when old enemies and the law arrive, forcing him to choose between his old life of violence and the new peaceful existence he has come to value.

About the Production

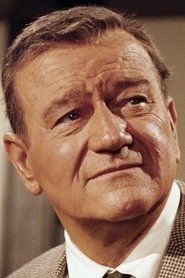

This was John Wayne's first production as an independent producer through Wayne-Fellows Productions. The film was initially planned for color photography but budget constraints forced a switch to black and white. Director James Edward Grant was primarily known as a screenwriter, making this his directorial debut. The production faced challenges with Gail Russell's fear of horses and her developing alcoholism, which required additional takes and patience from the cast and crew.

Historical Background

Released in 1947, 'Angel and the Badman' emerged during a pivotal period in American cinema and society. The immediate post-World War II era saw audiences seeking films that addressed themes of redemption, healing, and the possibility of personal transformation. The Western genre, traditionally focused on violence and frontier justice, began evolving to incorporate more complex psychological and moral themes. This film reflected America's broader cultural shift toward questioning violence and exploring spiritual alternatives. The Quaker pacifist element was particularly resonant in a world recovering from the devastation of global war. Additionally, 1947 marked the beginning of the Hollywood Blacklist era, and independent productions like Wayne's represented an alternative to the studio system that was coming under political scrutiny. The film's exploration of faith versus violence also reflected growing American spiritual searching in the post-war period.

Why This Film Matters

'Angel and the Badman' holds a distinctive place in cinema history as one of the first Westerns to seriously explore redemption through non-violent means and spiritual transformation rather than through gunplay. The film challenged the conventional Western narrative by suggesting that the toughest gunfighter could be redeemed not by outdrawing his enemies, but by embracing peace and love. This thematic innovation influenced countless subsequent Westerns, paving the way for more psychologically complex genre films like 'Shane' (1953) and 'The Searchers' (1956). The movie also represented John Wayne's evolution from actor to producer, demonstrating his growing influence on Hollywood and his desire to shape films that reflected his personal values. The film's portrayal of Quaker values introduced mainstream audiences to pacifist philosophy in an accessible format, contributing to broader cultural discussions about violence and conscience in American society.

Making Of

The production of 'Angel and the Badman' was marked by several significant challenges and innovations. James Edward Grant, primarily known as John Wayne's favorite screenwriter, was making his directorial debut, which led to Wayne effectively co-directing many scenes. The set atmosphere was reportedly tense due to Grant's learning curve and Wayne's perfectionism. Gail Russell, who played Penelope, struggled with both her fear of horses and a growing alcohol dependency that required additional support from the production. The Quaker aspects of the story were handled with unusual care for the era, with the production team consulting with actual Quaker representatives to ensure authentic representation of their beliefs and practices. The film's exploration of faith and redemption was somewhat revolutionary for the Western genre, which typically resolved conflicts through violence rather than spiritual transformation. Wayne's investment as producer allowed him greater creative control, resulting in a film that reflected his personal values about duty, honor, and the possibility of redemption.

Visual Style

The black and white cinematography by Archie Stout emphasizes the stark beauty of the American West while creating visual contrasts between the dark world of the gunfighter and the light of the Quaker community. Stout utilizes deep focus photography to create depth in scenes showing the isolation of the frontier homestead. The camera work often employs low angles when filming Wayne to emphasize his physical dominance, but uses more level framing in scenes with the Quaker family to suggest equality and community. The visual storytelling creates a clear dichotomy between the dusty, shadowy world of violence and the clean, well-lit environment of the Quaker home. Monument Valley locations provide the epic Western backdrop expected by audiences, while interior scenes are lit to suggest spiritual warmth and safety.

Innovations

While not groundbreaking in technical innovation, the film demonstrated notable achievements in blending genre conventions with more sophisticated psychological storytelling. The production successfully created authentic Quaker environments through careful set design and location choices. The film's sound engineering effectively captured both the expansive outdoor Western scenes and intimate interior moments without technical jarring. The editing by Richard L. Van Enger skillfully balanced action sequences with quieter character development moments, creating a rhythm that supported the film's thematic concerns about the pace of life and the value of reflection. The technical execution supported the film's artistic ambitions without drawing attention to itself, serving the story rather than showcasing technique.

Music

The musical score composed by Dale Butts and Morton Scott provides subtle emotional support without overwhelming the film's themes. The music incorporates elements reminiscent of hymns during Quaker scenes, reinforcing the spiritual aspects of the story. The score contrasts sweeping, traditional Western themes for action sequences with gentler, more intimate melodies for romantic and spiritual moments. The soundtrack notably avoids the bombastic music often associated with gunfighter Westerns, instead using more restrained compositions that reflect the film's contemplative approach to violence and redemption. The musical choices help bridge the gap between the Western genre conventions and the film's more innovative thematic concerns.

Famous Quotes

Quirt Evans: I've noticed that when a fellow starts talking about peace, it usually means he's getting ready to fight.

Penelope Worth: I don't believe in killing. I don't believe in guns. I don't believe in violence.

Thomas Worth: The Lord helps those who help themselves, but sometimes He needs a little help from us.

Quirt Evans: I'm not a religious man, but I'm beginning to think there might be something to this peace business.

Penelope Worth: It's not hard to love you, Quirt. It's just hard to understand you.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where Quirt Evans, wounded and unconscious, is discovered by the Quaker family as they return from church - establishing the film's central contrast between violence and peace.

- The scene where Quirt first attempts to participate in Quaker worship, sitting awkwardly in silence while the community engages in silent meditation, highlighting his alienation from their ways.

- The romantic moment when Penelope teaches Quirt to appreciate the beauty of a simple sunset, representing his gradual awakening to non-violent values.

- The climactic confrontation where Quirt faces his old enemy but chooses not to draw his gun, instead using words and moral authority to resolve the conflict.

- The final scene where Quirt, having chosen his new path, walks away from his old life without looking back, symbolizing his complete transformation.

Did You Know?

- This was the first film produced by John Wayne's own production company, Wayne-Fellows Productions

- James Edward Grant, the director, was primarily a screenwriter and this marked his only directorial effort

- The film was one of the first Westerns to explore redemption through love and religious faith rather than through violence

- Gail Russell was reportedly terrified of horses, requiring extensive coaching and special handling during riding scenes

- Harry Carey, who played the Quaker father, was a legendary Western star in his own right and this was one of his final film roles

- John Wayne effectively co-directed many scenes due to Grant's inexperience behind the camera

- The film was originally intended to be shot in Technicolor but budget restrictions forced the switch to black and white

- Wayne was so invested in the project that he took a reduced salary in exchange for a percentage of the profits

- The Quaker community was portrayed with unusual accuracy for the time, with the production consulting actual Quaker representatives

- The success of this film led Wayne and Grant to collaborate on several more projects including 'The Alamo' (1960)

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception was generally positive, with many reviewers noting the film's unusual approach to Western themes. The New York Times praised the film's 'unusual depth and sincerity' while Variety noted that Wayne 'brings a surprising sensitivity to his role.' Critics particularly appreciated the film's exploration of faith and redemption, with several reviews highlighting how it transcended typical genre conventions. Modern critics have reassessed the film as an important transitional work in the Western genre, with many considering it ahead of its time in its psychological approach to character development. The film is now recognized as an important precursor to the revisionist Westerns of the 1950s and 1960s, with particular appreciation for its nuanced treatment of morality and its rejection of simple violence as a solution to conflict.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by audiences and performed solidly at the box office, particularly among John Wayne's established fanbase. Moviegoers responded positively to the romantic elements and the unusual moral complexity of Wayne's character. Many viewers found the film's exploration of faith and redemption refreshing compared to more conventional Westerns of the era. The chemistry between Wayne and Russell was widely praised by audiences, with their romance providing an emotional anchor to the film's philosophical themes. Over time, the film has developed a cult following among Western enthusiasts who appreciate its unconventional approach to genre conventions. Modern audiences often express surprise at the film's progressive themes and its subtle critique of violence as a solution to problems.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards were won by this film

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Traditional Hollywood Westerns

- Quaker religious philosophy

- Post-war American spiritual searching

- John Ford's Westerns (particularly in visual style)

- The literary tradition of the redeemed outlaw

This Film Influenced

- Shane (1953)

- The Searchers (1956)

- The Magnificent Seven (1960)

- Unforgiven (1992)

- Dances with Wolves (1990)

- The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is well-preserved and has been restored several times. It entered the public domain in the United States, which has led to numerous releases of varying quality. The best versions come from restored prints maintained by film archives. The film has survived in excellent condition with no lost scenes or significant deterioration.