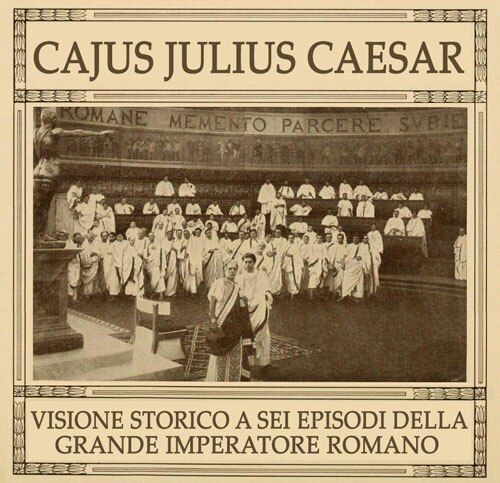

Cajus Julius Caesar

"Il più grandioso spettacolo cinematografico del mondo! (The grandest cinematic spectacle in the world!)"

Plot

This monumental Italian epic chronicles the life and political career of Julius Caesar, from his military campaigns in Gaul to his rise to power in Rome. The film portrays Caesar's complex relationship with his adopted son Brutus, who ultimately becomes his betrayer in the Senate conspiracy. Grand sequences depict Caesar's triumphs, the political machinations of the Roman Senate, and the famous assassination on the Ides of March. The narrative explores both Caesar's military genius and his personal vulnerabilities, culminating in the tragic betrayal by those he trusted most. The film concludes with the aftermath of Caesar's death and the beginning of Rome's transition from Republic to Empire.

About the Production

This was one of the most expensive and ambitious Italian productions of 1914, featuring massive sets including a reconstruction of the Roman Senate, thousands of extras, and elaborate battle sequences. The production utilized innovative techniques for crowd scenes and complex choreography. Director Enrico Guazzoni was known for his ability to orchestrate large-scale historical epics, having previously directed 'Quo Vadis' (1913). The film's sets were so impressive that they were reportedly reused in other productions for years afterward.

Historical Background

1914 was a pivotal year in world history, marking the beginning of World War I. In cinema, it represented the height of the Italian epic film industry, which was competing with Hollywood and European studios for international markets. Italy was a major film-producing country at this time, with Cines being one of its most important studios. The film was produced during a period of intense nationalism in Italy, and historical epics like this one served to celebrate Italy's Roman heritage. The film's release just months before the outbreak of WWI meant it was one of the last major international film releases before the war disrupted global cinema distribution. The early 1910s also saw the emergence of feature-length films as the industry standard, with epics like this one helping establish the format.

Why This Film Matters

'Cajus Julius Caesar' represents a crucial moment in the development of the epic film genre. Along with other Italian epics like 'Cabiria' and 'Quo Vadis', it helped establish many conventions of the historical epic that would influence filmmakers for decades, including D.W. Griffith and Cecil B. DeMille. The film demonstrated that cinema could handle complex historical narratives and large-scale productions, paving the way for later Hollywood epics. It also contributed to the international reputation of Italian cinema during its golden age. The film's success helped establish the commercial viability of feature-length historical epics and influenced how historical figures would be portrayed in cinema. Its techniques for managing large crowds and creating spectacular sequences would be studied and adapted by filmmakers worldwide.

Making Of

The production of 'Cajus Julius Caesar' represented the pinnacle of Italian cinema's golden age of epics (1910-1914). Director Enrico Guazzoni, building on his success with 'Quo Vadis', pushed the boundaries of what was possible in early cinema. The film required unprecedented coordination of thousands of extras, complex battle sequences, and elaborate sets. The Cines studio invested heavily in the production, constructing detailed replicas of ancient Roman architecture. The cast underwent extensive preparation, with Amleto Novelli studying historical depictions of Caesar. The film's cinematography, while limited by 1914 technology, used innovative techniques for crowd scenes and dramatic lighting. The production faced challenges including the logistics of managing large crowds and the technical limitations of early film equipment. Despite these challenges, the film was completed on schedule and became one of the most talked-about productions of 1914.

Visual Style

The cinematography, while limited by 1914 technology, was ambitious for its time. The film used wide shots to capture the scale of massive crowd scenes and elaborate sets. The lighting techniques, though primitive by modern standards, attempted to create dramatic shadows and highlights, particularly in interior scenes like the Senate. The camera work included some movement and varied angles, which was innovative for the period. The battle sequences used multiple camera positions to create a sense of action and scale. The black and white photography emphasized the dramatic contrasts in the story, from the grandeur of Roman triumphs to the darkness of the conspiracy. The film's visual style influenced how historical epics would be photographed for years to come.

Innovations

The film pushed the boundaries of early cinema in several technical areas. Its use of massive sets and thousands of extras required innovations in crowd management and scene choreography. The production developed new techniques for creating the illusion of even larger crowds through clever camera positioning and editing. The battle sequences featured complex staging that influenced how action scenes would be filmed in subsequent epics. The film's set design and construction techniques for historical buildings were groundbreaking and would be studied by other filmmakers. The production also pioneered methods for coordinating multiple units shooting simultaneously, a necessity for such a large-scale production. These technical achievements helped establish the vocabulary of epic filmmaking that would be refined and expanded in later decades.

Music

As a silent film, 'Cajus Julius Caesar' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical score would have been compiled from classical pieces, including works by composers like Verdi and Wagner, whose dramatic music suited the epic nature of the film. Some theaters may have used original compositions specifically written for the film. The music would have varied dramatically to match the on-screen action, with triumphant marches for Caesar's victories, tense dramatic passages for the conspiracy scenes, and mournful music for the assassination and aftermath. Unfortunately, no specific information about the original musical accompaniment has survived, as was common with films of this era.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, dialogue was conveyed through intertitles. Key moments included the Senate conspirators' declaration of their intentions, Caesar's final words of betrayal, and Brutus's conflicted expressions throughout the narrative.

Memorable Scenes

- The assassination scene in the Roman Senate, featuring dramatic staging of the conspirators surrounding Caesar, was particularly praised by contemporary critics for its emotional intensity and choreography. The triumphal entry into Rome showcased the film's spectacular scale with thousands of extras and elaborate sets. The confrontation scenes between Caesar and Brutus emphasized their complex relationship through expressive silent acting.

Did You Know?

- This film was released in the same year as Giovanni Pastrone's 'Cabiria', another landmark Italian epic that would influence cinema worldwide.

- The film featured thousands of extras, making it one of the largest productions of its time.

- Amleto Novelli, who played Caesar, was one of Italy's most popular silent film stars of the 1910s.

- The film's sets were so elaborate and expensive that they were reportedly preserved and reused in other Italian films for several years.

- Director Enrico Guazzoni was a pioneer of the Italian epic genre, having previously directed the successful 'Quo Vadis' in 1913.

- The film was distributed internationally and was particularly successful in the United States, where it was praised for its spectacle.

- The assassination scene in the Senate was particularly praised by contemporary critics for its dramatic intensity and staging.

- The film's title uses 'Cajus' instead of the more common 'Gaius' - this was an alternative Latin spelling used in some historical texts of the period.

- The production reportedly employed actual Roman ruins and locations for authenticity, supplementing with massive studio sets.

- The film was one of the last major Italian epics before World War I disrupted European film production.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film for its spectacular scale and ambitious scope. Reviews in trade publications like 'The Moving Picture World' and 'Variety' highlighted the impressive sets, large crowds, and dramatic intensity. The performances, particularly Amleto Novelli as Caesar, were noted for their theatrical power appropriate to the silent medium. Modern film historians consider the film an important example of early Italian epic cinema, though many note that it has been overshadowed by 'Cabiria' in historical memory. Critics have pointed out that while the film's technical achievements were impressive for 1914, some of the pacing and narrative techniques feel dated by modern standards. The assassination scene remains frequently cited as an example of effective dramatic staging in early cinema.

What Audiences Thought

The film was a commercial success both in Italy and internationally, particularly in the United States where Italian epics were popular. Audiences were impressed by the spectacular scale and the opportunity to see historical events brought to life. The film's dramatic moments, especially the assassination sequence, reportedly elicited strong reactions from contemporary audiences. In Italy, the film appealed to national pride in the country's Roman heritage. The success of this and other Italian epics helped establish international audiences' appetite for historical spectacles. However, the outbreak of World War I shortly after its release limited its long-term international distribution, as the war disrupted film markets across Europe.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Shakespeare's 'Julius Caesar'

- Plutarch's 'Lives'

- Roman historical texts

- Earlier Italian historical films

- Theatrical traditions of historical drama

This Film Influenced

- 'Cabiria' (1914)

- 'Intolerance' (1916)

- 'The Ten Commandments' (1923)

- 'Ben-Hur' (1925)

- 'Julius Caesar' (1953)

- 'Spartacus' (1960)

- 'Cleopatra' (1963)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is believed to be partially lost or only surviving in fragments, which is common for films from this era. Some sequences may exist in film archives, but a complete version has not been definitively located. The Cineteca Nazionale in Italy and other international film archives may hold portions of the film. The loss of many Italian epics from this period makes this film particularly significant for film historians studying the development of the genre.