Carmen

"The Screen's Supreme Triumph in the Art of Motion Picture Production"

Plot

In 19th-century Seville, Spain, the passionate and free-spirited gypsy Carmen works at a cigarette factory where she captivates all who meet her. When she is arrested for assaulting a co-worker, she seduces her guard, the naive and honorable corporal Don Jose, who allows her to escape. Don Jose deserts the army and joins Carmen's band of smugglers, abandoning his childhood sweetheart and his military career for his obsession with the gypsy. However, Carmen's fickle heart soon turns to the dashing bullfighter Escamillo, whose fame and prowess in the arena attract her attention. Consumed by jealousy and rage when Carmen rejects him completely, Don Jose confronts her outside the bullring during Escamillo's triumph and, in a desperate final plea, stabs her to death when she refuses to return to him, realizing too late that his passion has destroyed everything he once held dear.

About the Production

This was the first film to feature Metropolitan Opera star Geraldine Farrar, marking a significant crossover from opera to cinema. The production was ambitious for its time, featuring elaborate sets recreating 19th-century Seville and authentic Spanish costumes. DeMille insisted on filming actual bullfighting sequences in San Diego, though he carefully staged them to avoid animal cruelty. The film was shot in just three weeks but featured unprecedented attention to detail in set design and costuming, setting new standards for production values in American cinema.

Historical Background

1915 was a pivotal year in American cinema, occurring during the transition from short films to feature-length productions and coinciding with the early years of World War I in Europe. The film industry was consolidating in Hollywood, with studios like the Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company (which would later become Paramount Pictures) establishing the studio system. This period saw the rise of the feature film as the dominant form of cinematic entertainment, with directors like Cecil B. DeMille pioneering techniques that would define classical Hollywood cinema. The war in Europe had disrupted European film production, creating an opportunity for American films to dominate international markets. 'Carmen' emerged during this transformative period, demonstrating how American cinema could adapt European artistic works for mass audiences while establishing its own distinctive style and production values.

Why This Film Matters

'Carmen' holds a significant place in cinema history as one of the first successful adaptations of a major opera to the screen, demonstrating that silent films could convey complex emotions and sophisticated narratives without dialogue or music. The film helped legitimize cinema as an art form capable of adapting high culture, bridging the gap between 'respectable' arts like opera and the then-lowbrow medium of motion pictures. Its commercial success proved that audiences would respond to serious dramatic content, paving the way for more ambitious literary and theatrical adaptations. The film also established the star power crossover potential, showing that established artists from other media could find success in cinema. DeMille's approach to visual storytelling in 'Carmen' influenced how directors would use mise-en-scène, lighting, and composition to convey emotional depth in silent films. The movie's treatment of themes of passion, jealousy, and cultural conflict also reflected America's growing engagement with European culture and its own ethnic tensions during the early 20th century.

Making Of

The production of 'Carmen' marked a significant milestone in early Hollywood history, representing the collaboration between the established world of opera and the burgeoning film industry. Geraldine Farrar's casting was a major coup for producer Jesse Lasky, as she was one of the most celebrated opera singers of her era. DeMille worked closely with Farrar to adapt her stage techniques for the camera, teaching her the subtleties of screen acting while preserving her dramatic intensity. The director was meticulous in his approach, insisting on authentic Spanish architecture and costumes, even importing materials from Spain for the set construction. The bullfighting sequences proved particularly challenging, as DeMille wanted to capture the spectacle without glorifying violence. He worked with professional matadors but carefully controlled the filming to ensure no animals were harmed. The film's success surprised many in the industry who doubted that opera audiences would embrace cinema, but it proved that sophisticated artistic works could find new life on screen.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Carmen' was groundbreaking for its time, featuring innovative use of lighting, composition, and camera movement that elevated it above typical productions of the era. DeMille and his cinematographer, Alvin Wyckoff, employed sophisticated lighting techniques to create dramatic shadows and highlights that enhanced the emotional intensity of key scenes. The film made extensive use of location shooting, particularly for the bullfighting sequences and outdoor scenes, which was relatively uncommon for major productions of the period. Wyckoff's camera work included subtle movements and framing choices that emphasized the psychological states of the characters, using close-ups strategically to highlight emotional moments. The film also featured elaborate set designs with deep focus that allowed for complex staging within the frame, creating a sense of depth and realism that was unusual for 1915. The color tinting of the film was particularly sophisticated, with different hues used to establish mood and time of day, demonstrating an early understanding of how color could enhance narrative impact even in a black and white medium.

Innovations

'Carmen' featured several technical innovations that advanced the art of filmmaking in 1915. The production employed sophisticated set design techniques, including forced perspective and detailed matte paintings to create the illusion of 19th-century Seville. The film's use of color tinting was particularly advanced for its time, with different hues applied to scenes based on their emotional content and time of day. The bullfighting sequences required innovative camera placement and movement to capture the action effectively while maintaining dramatic tension. The film also featured some of the earliest examples of carefully controlled lighting effects to create mood and emphasize psychological states, with DeMille experimenting with backlighting and shadow play to enhance the dramatic impact of key scenes. The production also pioneered techniques for crowd control and choreography, particularly in the cigarette factory scene which featured hundreds of extras moving in coordinated patterns. These technical achievements helped establish new standards for production quality in American cinema and influenced how subsequent films would approach visual storytelling.

Music

As a silent film, 'Carmen' featured no recorded dialogue or synchronized music, but was accompanied by live musical performances during theatrical exhibitions. The film's success prompted the publication of a specially compiled score by composer Hugo Riesenfeld, who created arrangements based on Bizet's original opera music along with original compositions. This was one of the first instances of a film having a specifically composed musical score rather than relying on theater organists to improvise or use pre-existing classical pieces. The score incorporated themes from Bizet's opera, cleverly adapted to match the film's pacing and emotional arcs, allowing audiences familiar with the opera to recognize the musical motifs while creating an appropriate accompaniment for those who weren't. The music emphasized the Spanish setting through the use of castanets, guitars, and other traditional instruments in the orchestration. The success of this approach influenced how other studios would commission original scores for their major productions, helping establish film music as a serious artistic endeavor.

Famous Quotes

"The law is a strange thing. It makes a man forget his honor." (Don Jose)

"I am free. I was born free, and free I will die." (Carmen)

"Love is a rebellious bird that no one can tame." (Carmen)

"You think you own me because you love me? You own nothing!" (Carmen)

"Better to die free than live in chains." (Carmen)

Memorable Scenes

- The seduction scene where Carmen first charms Don Jose, using her flower as a symbol of her dangerous allure and his inevitable downfall.

- The cigarette factory riot where Carmen's fiery nature is first revealed as she attacks another woman, establishing her character as untamable and dangerous.

- The smugglers' camp scene where Carmen and Don Jose dance together, their movements conveying the growing passion and underlying tension of their relationship.

- The bullfight sequence where Escamillo triumphs in the arena while Carmen watches with admiration, visually establishing her shifting affections and setting up the final tragedy.

- The climactic confrontation outside the bullring where Don Jose's desperate pleas turn to violence, culminating in Carmen's famous final defiance and death.

Did You Know?

- Geraldine Farrar was one of the Metropolitan Opera's biggest stars when she made this film, becoming one of the first major opera singers to transition to motion pictures.

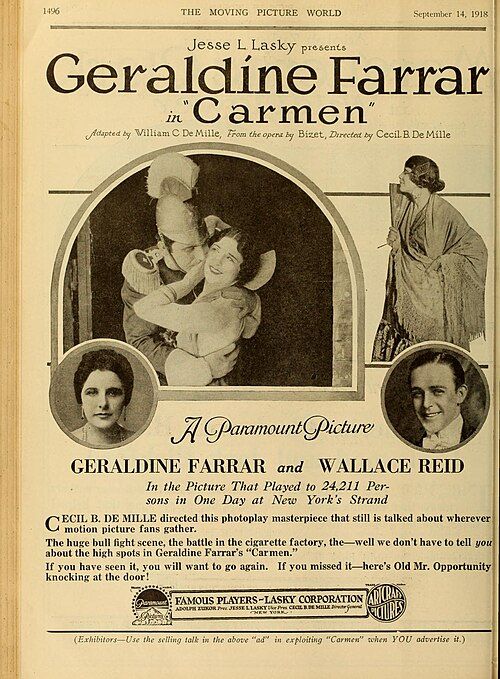

- The film was so successful that it was re-released in 1918 with new tinting and additional scenes to capitalize on its continued popularity.

- Cecil B. DeMille considered this one of his most important early films, establishing his reputation for lavish productions and dramatic storytelling.

- Wallace Reid, who played Don Jose, would become one of the biggest male stars of the silent era before his tragic death from morphine addiction in 1923.

- The film was shot on location at the Lasky Ranch, which would later become the site of the Hollywood Bowl.

- Farrar's contract for this film was unprecedented at the time, paying her $2,500 per week plus a percentage of the profits.

- The cigarette factory scene featured over 300 extras, all women, carefully choreographed to create the impression of a bustling factory environment.

- DeMille used innovative color tinting techniques, with amber tones for outdoor scenes and blue tints for night sequences.

- The film's success led to Farrar making several more films with DeMille, including 'Joan the Woman' (1917).

- This was one of the first films to feature a full orchestral score composed specifically for the production, rather than using pre-existing classical pieces.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'Carmen' as a triumph of cinematic art, with The Moving Picture World declaring it 'the finest motion picture ever produced' and marveling at its technical achievements and emotional power. Critics particularly praised Geraldine Farrar's performance, noting how successfully she translated her operatic intensity to the screen medium. The New York Dramatic Mirror wrote that the film 'elevates the motion picture to a plane of artistry hitherto unattained.' Modern critics and film historians view 'Carmen' as a crucial transitional work in DeMille's career and in the development of American cinema. Kevin Brownlow, in his book 'The Parade's Gone By,' highlights the film's sophisticated visual storytelling and its role in establishing DeMille's directorial style. The film is now recognized as an important example of early feature filmmaking and as a significant step in the evolution of cinematic language, particularly in how it uses visual composition and performance to convey complex emotional states without dialogue.

What Audiences Thought

The film was a tremendous commercial success, breaking box office records across the country and running for unprecedented engagements in major cities. Audiences were particularly drawn to Geraldine Farrar, whose operatic fame brought a new type of prestige to motion picture attendance. Many theater patrons who had previously dismissed films as vulgar entertainment were attracted by Farrar's participation, expanding cinema's audience to include more middle-class and upper-class viewers. The film's passionate story and dramatic intensity resonated strongly with contemporary audiences, who were experiencing the upheavals of World War I and found in Carmen's tragic story a reflection of their own turbulent times. The success of 'Carmen' helped establish the feature film as the dominant form of entertainment and demonstrated that sophisticated dramatic content could be commercially viable, encouraging studios to invest in more ambitious productions.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards were given for films in 1915, as the first Academy Awards ceremony would not occur until 1929

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Georges Bizet's opera 'Carmen' (1875)

- Prosper Mérimée's novella 'Carmen' (1845)

- Italian verismo opera tradition

- Spanish literary romanticism

- Silent film melodrama conventions

- Stage melodrama techniques

This Film Influenced

- Carmen (1926) directed by Raoul Walsh

- The Loves of Carmen (1948) directed by Charles Vidor

- Carmen (1983) directed by Carlos Saura

- Carmen (1984) directed by Francesco Rosi

- Numerous later film adaptations of the Carmen story

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

A complete nitrate print of 'Carmen' is preserved in the Library of Congress collection, and the film has been made available through various archival screenings and home video releases. The George Eastman Museum also holds materials related to the film's production and promotion. The film underwent restoration in the 1990s, which included recreating the original color tinting schemes and stabilizing the deteriorating nitrate elements. While some scenes show signs of nitrate decomposition, the film is considered to be in relatively good condition for a production of its era. The restoration work has allowed modern audiences to appreciate the film's visual sophistication and artistic achievements nearly intact from DeMille's original vision.