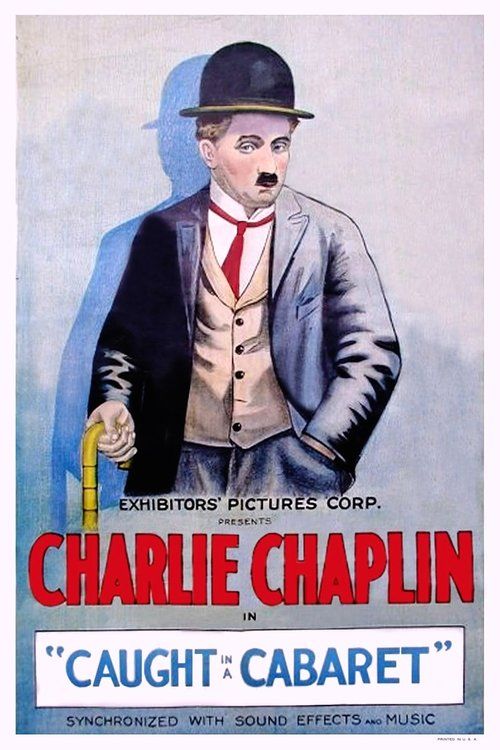

Caught in a Cabaret

Plot

Charlie plays a clumsy waiter working at a cheap cabaret who constantly suffers under the strict orders of his demanding boss. During his break time, he meets a pretty young woman in the park and attempts to impress her by pretending to be a sophisticated ambassador. The deception leads to complications when he discovers the woman has a jealous fiancé who eventually follows Charlie back to his workplace. When the fiancé arrives at the cabaret and discovers Charlie's true identity as a mere waiter, chaos erupts resulting in a comedic confrontation that exposes Charlie's lies and culminates in typical Keystone slapstick mayhem.

About the Production

This film was produced during Charlie Chaplin's first year at Keystone Studios, a period when he was still developing his iconic Tramp character. Mabel Normand, one of the few female directors of the era, both directed and starred in the film, showcasing her significant influence at Keystone. The production utilized typical Keystone methods of improvisation and spontaneous gags, with Chaplin already beginning to assert creative control over his material despite being relatively new to the studio.

Historical Background

1914 was a pivotal year in cinema history, marking the transition from short films to feature-length productions and the establishment of Hollywood as the center of American filmmaking. The film industry was rapidly evolving from a novelty attraction to a legitimate art form and business. When 'Caught in a Cabaret' was released, World War I had just begun in Europe, though America remained neutral. This period saw the rise of the studio system, with Keystone Studios under Mack Sennett leading the way in comedy production. The film emerged during the golden age of silent comedy, when physical humor and visual storytelling were being perfected. It also represents a time when women like Mabel Normand could wield significant creative power in Hollywood, a situation that would become increasingly rare as the studio system became more rigid and male-dominated in subsequent decades.

Why This Film Matters

'Caught in a Cabaret' holds importance as an early example of Charlie Chaplin's developing genius and as a showcase of Mabel Normand's pioneering role as a female director. The film contributes to our understanding of how the Keystone comedy style was developed and how Chaplin's iconic Tramp character evolved. It represents a moment when gender roles in filmmaking were more flexible than they would become in later decades, with Normand successfully directing one of cinema's greatest comedians. The film also exemplifies the transition from stage comedy to film comedy, showing how cinematic techniques were being adapted to enhance physical humor. Its preservation allows modern audiences to witness the early development of screen comedy and the collaborative nature of early filmmaking, where stars often took on multiple creative roles.

Making Of

The making of 'Caught in a Cabaret' represents a fascinating moment in early cinema history when creative roles were more fluid and experimental. Mabel Normand, already a major star at Keystone, was expanding her influence behind the camera during a time when very few women held directorial positions. Chaplin, still relatively new to film, was already beginning to assert his creative vision and develop the comedic techniques that would make him world-famous. The production followed typical Keystone methods of rapid shooting with minimal scripting, relying heavily on improvisation and the performers' comedic instincts. The relationship between Normand and Chaplin was complex and often contentious, with Chaplin already showing his perfectionist tendencies while Normand represented the established Keystone order. This film was part of a series of collaborations between the two that helped establish both their careers and the Keystone style of comedy.

Visual Style

The cinematography in 'Caught in a Cabaret' follows typical Keystone Studios practices of the era, with static camera positions and wide shots designed to capture the full range of physical comedy. The film was likely shot on 35mm film with the standard cameras of the period. The lighting is naturalistic, utilizing available light for the outdoor park scenes and basic studio lighting for the interior cabaret sequences. The camera work prioritizes clarity of action over artistic flourishes, ensuring that the slapstick gags and character movements are clearly visible to the audience. The cinematography effectively serves the comedy by maintaining consistent framing that allows the physical humor to play out without visual confusion.

Innovations

While 'Caught in a Cabaret' doesn't feature groundbreaking technical innovations, it represents the refinement of existing film techniques for comedy. The film demonstrates the effective use of cross-cutting between the park and cabaret locations to build comedic tension. The editing follows the rhythm of the gags, with timing that enhances the physical humor. The production utilized the efficient Keystone studio system, which could produce films quickly while maintaining quality. The film shows how early filmmakers were learning to use the medium specifically for comedy, developing techniques that would become standard in the genre. The use of real locations combined with studio sets also demonstrates the hybrid approach to filmmaking that was common in this transitional period.

Music

As a silent film, 'Caught in a Cabaret' originally would have been accompanied by live music in theaters, typically piano or organ accompaniment. The specific musical score was not standardized, with individual theaters providing their own musical interpretations. The accompaniment would have followed the dramatic and comedic beats of the film, with lively music during the slapstick sequences and more romantic themes during the park scenes. Modern restorations and screenings often feature newly composed scores or period-appropriate music that reflects the 1914 era. The lack of synchronized sound meant that all comedy had to be visual, which influenced the film's emphasis on physical gags and expressive performances.

Memorable Scenes

- The park scene where Charlie first meets the pretty girl and begins his ambassador impersonation, showcasing early Chaplin charm and comedic timing

- The chaotic confrontation in the cabaret when the jealous fiancé discovers Charlie's true identity, resulting in Keystone-style slapstick mayhem with flying dishes and physical comedy

- Charlie's awkward attempts to maintain his ambassador persona while actually working as a waiter, creating humor through the contrast between his pretensions and reality

Did You Know?

- This was one of the first films that Mabel Normand directed, making her one of the earliest female directors in cinema history.

- Charlie Chaplin and Mabel Normand had a complex professional and personal relationship, with this film being one of their many collaborations.

- The film was released just three months after Chaplin joined Keystone Studios in January 1914.

- This movie showcases Chaplin's character before the Tramp persona was fully developed, though elements of the famous character are beginning to emerge.

- Keystone Studios produced films at an incredible pace, often releasing multiple short comedies each week.

- The park scenes were likely filmed at Echo Park in Los Angeles, a common filming location for Keystone productions.

- Phyllis Allen, who plays the jealous fiancé's mother, was a regular Keystone actress who appeared in over 150 films.

- The cabaret set was a typical Keystone construction, designed to be easily modified for multiple productions.

- This film was released during the early days of feature-length films, when short comedies were still the standard format.

- Mabel Normand was not only a director and actress but also a writer and producer, making her one of the most versatile women in early Hollywood.

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of 'Caught in a Cabaret' were generally positive, with trade publications noting Chaplin's growing comedic skills and Normand's capable direction. The Moving Picture World praised the film's 'laugh-provoking situations' and noted the chemistry between the leads. Modern critics view the film as an important historical document showing Chaplin's early development, though it's generally considered less sophisticated than his later work. Film historians appreciate the movie for its demonstration of Normand's directorial abilities and its place in the Keystone comedy canon. The film is often analyzed in studies of early cinema and women's roles in film production, with scholars noting its significance despite its relatively simple plot and typical Keystone structure.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1914 responded enthusiastically to 'Caught in a Cabaret,' as it featured the rapidly rising star Charlie Chaplin alongside the established favorite Mabel Normand. The film's combination of slapstick humor, romantic comedy elements, and the novelty of seeing Chaplin in a waiter's uniform rather than his full Tramp costume appealed to contemporary moviegoers. The cabaret setting was particularly relatable to urban audiences of the time. Modern audiences viewing the film through archival screenings or home media appreciate it as a historical artifact that showcases early comedy techniques and the beginnings of Chaplin's legendary career, though some find the pacing and humor dated compared to later silent comedies.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- French and Italian comedies of the early 1910s

- Vaudeville and music hall traditions

- Mack Sennett's Keystone comedy style

- Stage farce traditions

This Film Influenced

- Later Chaplin films featuring class deception themes

- Keystone comedies of 1914-1915

- Workplace comedy films

- Romantic comedy shorts of the silent era

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in complete form and has been preserved by various film archives. Prints are held at the Library of Congress, the Museum of Modern Art, and other major film institutions. The film has been restored and is available through various home media releases and digital platforms. The survival rate of Keystone films is relatively low, making the preservation of this particular title valuable for film history. Some versions show varying degrees of deterioration, but the essential content remains intact and viewable.