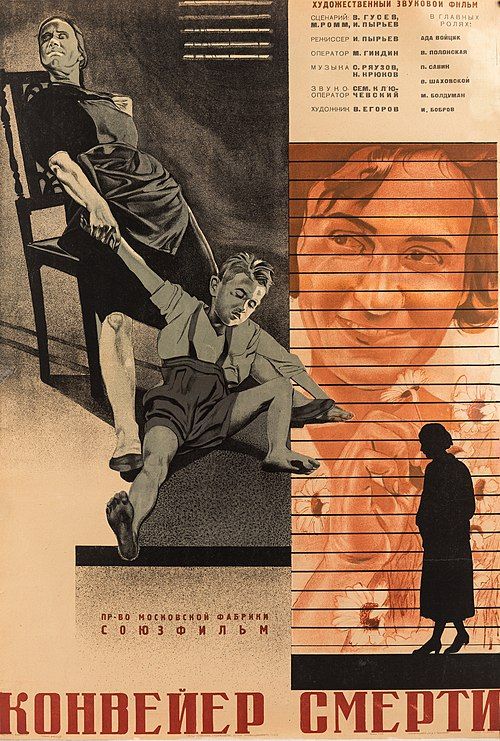

Conveyor of Death

Plot

Set in a fictional capitalist country during the Great Depression, 'Conveyor of Death' follows three young female factory workers whose dreams of prosperity are shattered when economic crisis forces them onto the streets. Each woman embarks on a different desperate path: one turns to prostitution, another becomes involved in labor organizing, while the third attempts to maintain her dignity despite overwhelming hardship. The film portrays their struggles against the brutal capitalist system that treats workers as disposable cogs in an economic machine. As their situations deteriorate, the women encounter the stark realities of unemployment, exploitation, and social abandonment. The narrative serves as a stark indictment of capitalist society while implicitly praising the Soviet alternative. The film culminates in a powerful critique of the dehumanizing effects of unchecked capitalism on ordinary workers.

About the Production

The film was produced during the height of Stalin's first Five-Year Plan and represents classic Soviet socialist realist cinema. Director Ivan Pyryev was relatively early in his career but would go on to become one of the Soviet Union's most celebrated directors, winning multiple Stalin Prizes. The production faced the typical constraints of Soviet filmmaking in the 1930s, including strict ideological oversight by Glavlit (the Main Administration for Literary and Publishing Affairs) to ensure the film properly reflected Communist Party messaging about the evils of capitalism.

Historical Background

The film was produced in 1933, a pivotal year in world history. The Great Depression was at its nadir in the capitalist West, with unemployment reaching devastating levels in the United States and Europe. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union was in the midst of Stalin's first Five-Year Plan (1928-1932), a period of rapid industrialization and collectivization that the Soviet government promoted as evidence of the superiority of communism. The film was created as part of the Soviet cultural campaign to showcase the 'crisis of capitalism' to domestic audiences and contrast it with Soviet 'progress.' This was also the period when socialist realism was being established as the official artistic doctrine of the Soviet Union. The film reflects the intense ideological struggle of the 1930s and the Soviet Union's efforts to convince its citizens of the righteousness of their system despite the hardships of collectivization and industrialization.

Why This Film Matters

'Conveyor of Death' represents a classic example of early Soviet propaganda cinema and the socialist realist style that would dominate Soviet arts for decades. The film contributed to the cultural narrative that framed the Great Depression as evidence of capitalism's inevitable collapse while portraying the Soviet Union as a worker's paradise. It helped establish visual and narrative tropes that would become standard in Soviet depictions of the West: cold, mechanical environments contrasted with warm, collective Soviet life. The film also reflects the gender politics of early Soviet cinema, which, despite promoting women's emancipation, often portrayed female characters as victims of capitalist exploitation needing rescue by the socialist system. While largely forgotten today, the film is historically significant as a artifact of the cultural Cold War that began long before the political Cold War of the post-World War II era.

Making Of

The production of 'Conveyor of Death' took place during a critical period in Soviet cinema history when Stalin was consolidating his control over the arts. The film was made under the strict guidelines of socialist realism, which demanded that art be realistic in form and socialist in content. Director Ivan Pyryev, though still early in his career, understood the political requirements and crafted a film that served as both entertainment and propaganda. The casting process was influenced by the actors' political reliability as much as their talent. The factory scenes were filmed at working Soviet industrial plants, requiring coordination with factory managers and often disrupting production. The film's score was composed to emphasize the emotional contrast between the 'cold, mechanical' capitalist world and the 'warm, human' Soviet alternative. Post-production involved extensive review by party officials to ensure the ideological message was clear and uncompromising.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Vladimir Nikolaev employs stark visual contrasts to emphasize the ideological message. The capitalist factory scenes are shot with harsh lighting, angular compositions, and mechanical rhythms to create a sense of dehumanization and oppression. The camera work emphasizes the repetitive, soul-destroying nature of industrial labor under capitalism through long takes of machinery and assembly lines. In contrast, scenes of human interaction are shot with softer lighting and more fluid camera movements to suggest the possibility of warmth and connection outside the capitalist system. The film makes effective use of shadows and silhouettes, particularly in scenes depicting the characters' despair and isolation. The visual style is characteristic of early Soviet sound cinema, which was transitioning from the experimental montage techniques of the silent era to the more narrative-driven approach required by sound technology.

Innovations

As an early Soviet sound film, 'Conveyor of Death' represents the technical transition from silent to sound cinema in the USSR. The film demonstrates sophisticated use of sound for narrative and ideological purposes, particularly in how it contrasts mechanical noise with human voices. The production made effective use of location shooting in actual factories, which presented technical challenges for recording clear dialogue in noisy industrial environments. The film's editing techniques show the influence of Soviet montage theory while adapting to the demands of sound cinema. The cinematography successfully integrates visual storytelling with the new technical possibilities of sound, creating a cohesive audiovisual experience that serves the film's propaganda purpose.

Music

The film's score was composed by Lev Shvarts, who was known for his work on Soviet propaganda films. The music employs stark contrasts between mechanical, dissonant themes for the capitalist factory scenes and more lyrical, hopeful melodies for moments of human connection and resistance. The soundtrack makes effective use of industrial sounds - machinery, whistles, and factory noise - to create an oppressive atmosphere that underscores the film's themes. The musical score follows the principles of socialist realism by being accessible to mass audiences while clearly supporting the film's ideological message. The sound design emphasizes the dehumanizing nature of the capitalist workplace through the constant presence of mechanical noise that drowns out human voices and individual expression.

Did You Know?

- Director Ivan Pyryev later became one of the most decorated Soviet filmmakers, winning six Stalin Prizes throughout his career

- The film was part of a wave of Soviet 'capitalist horror' films produced in the early 1930s to contrast Western economic suffering with Soviet 'progress'

- Mikhail Astangov, who plays one of the lead roles, was known for his powerful screen presence and later became a People's Artist of the USSR

- The film's title 'Conveyor of Death' refers both to the literal factory conveyor belt and the metaphorical 'conveyor' of capitalism that consumes workers

- Veronika Polonskaya was notably the last lover of poet Vladimir Mayakovsky before his suicide in 1930

- The film was shot on location at actual Soviet factories to add authenticity to the industrial settings

- Like many Soviet films of this era, it was subject to multiple revisions by state censors before approval

- The film's release coincided with the worst year of the Great Depression in the United States, maximizing its propaganda impact

- Mikhail Bolduman, another lead actor, was a prominent stage actor at the Moscow Art Theatre before transitioning to film

- The film was rarely shown outside the Soviet Union due to its explicitly anti-capitalist message

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film for its clear ideological message and effective portrayal of capitalist exploitation. Reviews in Soviet publications like 'Pravda' and 'Izvestia' highlighted the film's powerful indictment of the capitalist system and its emotional impact on viewers. The film was noted for its strong performances, particularly by Mikhail Astangov, and for Ivan Pyryev's assured direction. Western critics, when they had the rare opportunity to see the film, typically dismissed it as crude propaganda, though some acknowledged its technical competence within the constraints of its political purpose. Modern film historians view the film as an important example of early Soviet sound cinema and a revealing artifact of Stalinist cultural policy, though generally not as one of Pyryev's most artistically significant works compared to his later films like 'The Swineherd and the Shepherd' (1941) and 'Kuban Cossacks' (1949).

What Audiences Thought

Soviet audiences of the 1930s generally received the film positively, as it reinforced the official narrative about the superiority of the Soviet system during a time when many Soviet citizens were experiencing genuine hardship due to collectivization and rapid industrialization. The film provided a powerful contrast to the reality of Soviet life, suggesting that despite current difficulties, the future would be bright under socialism. The emotional stories of the three female protagonists resonated with working-class audiences who could relate to economic insecurity, even if the capitalist setting was foreign to them. The film was reportedly popular in workers' clubs and factory screenings, where it was often followed by political discussions. However, like many Soviet films of this era, its reception was likely influenced by the political pressure to respond enthusiastically to works that supported party ideology.

Awards & Recognition

- None documented - Soviet films of this era typically did not participate in international film festivals

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Soviet montage theory

- Socialist realist doctrine

- German Expressionism (visual style)

- Eisenstein's Strike (1925) (thematic influence)

- Pudovkin's The End of St. Petersburg (1927) (ideological influence)

This Film Influenced

- Other Soviet 'capitalist horror' films of the 1930s

- Pyryev's later socialist realist works

- Cold War era propaganda films from both sides