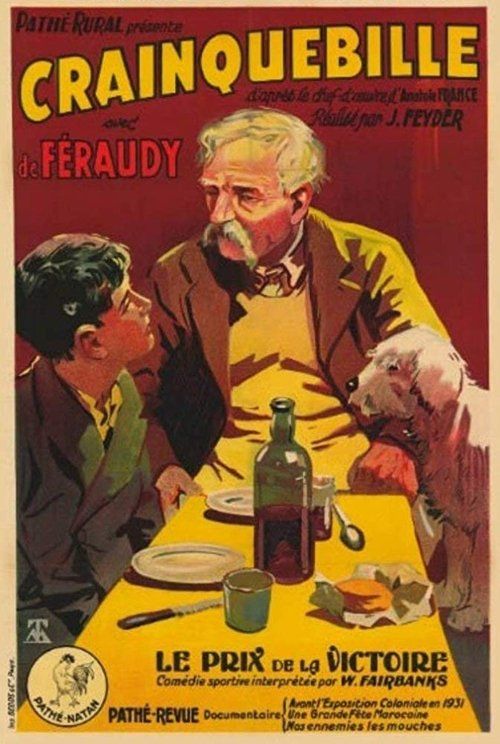

Crainquebille

Plot

Jérôme Crainquebille is an elderly vegetable seller who has faithfully operated his cart in the streets of Paris for over four decades. His peaceful existence is shattered when a young police officer harasses him and demands he move his cart. When Crainquebille protests the unfair treatment, he is arrested on false charges of insulting the officer, leading to a humiliating trial where he's convicted despite his innocence. After serving his sentence, Crainquebille finds himself ostracized by society, his customers abandoning him and his reputation destroyed. The film follows his descent into poverty and despair, his brief connection with a young street urchin named 'La Môme' who shows him kindness, and his ultimate tragic fate as a victim of an unjust system. The story serves as a powerful indictment of social injustice and the dehumanizing effects of bureaucracy on ordinary people.

About the Production

The film was based on the 1901 story 'L'Affaire Crainquebille' by Nobel Prize-winning author Anatole France. Jacques Feyder, who had recently returned from working in Germany, brought German cinematic techniques to French cinema with this production. The film was shot on location in Paris to capture the authentic atmosphere of the city's working-class neighborhoods. The production faced challenges recreating the Parisian street scenes authentically, with the crew often having to clear actual streets of modern traffic and pedestrians to maintain period accuracy.

Historical Background

The film was produced during the early years of the French Third Republic, a period marked by social tensions between the working class and the authorities. France was still recovering from World War I, with many veterans struggling to reintegrate into society and high unemployment rates. The film's themes of injustice and abuse of authority resonated strongly with audiences who had experienced similar frustrations with bureaucracy and police power. The early 1920s also saw the rise of French cinematic realism, with directors moving away from theatrical traditions toward more naturalistic storytelling. This film emerged alongside other socially conscious French works that critiqued the establishment, reflecting a broader cultural shift toward questioning authority and traditional institutions in post-war Europe.

Why This Film Matters

Crainquebille represents a landmark in French cinema's development of social realism and narrative sophistication. The film was among the first to seriously address class conflict and institutional injustice in French society, paving the way for later French poetic realist films of the 1930s. Its visual style influenced subsequent French directors in its use of authentic locations and naturalistic performances. The film's critical view of police authority was relatively bold for its time and contributed to growing public discourse about police reform in France. Maurice de Féraudy's performance set a new standard for dramatic acting in French cinema, demonstrating how silent film could convey complex emotional states without dialogue. The film also helped establish the career of Jacques Feyder as one of France's most important early directors, and its success encouraged other French filmmakers to tackle socially relevant subjects.

Making Of

Jacques Feyder approached this adaptation with a strong social consciousness, having witnessed similar injustices during his time in Germany during World War I. The casting of Maurice de Féraudy was deliberate - Feyder wanted an actor whose face could convey the weight of forty years of honest labor. The young Jean Forest was discovered by Feyder in a Parisian playground and given his first major role. The film's production coincided with a period of social unrest in France, with many workers' strikes occurring, which added to the film's contemporary relevance. Feyder insisted on using real Parisian locations rather than studio sets to achieve greater authenticity, a relatively innovative approach for French cinema at the time. The film's courtroom scenes were particularly challenging to shoot, as Feyder wanted to capture the oppressive atmosphere of the French judicial system without dialogue, relying entirely on visual storytelling and actors' expressions.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Léonce-Henri Burel employed innovative techniques for capturing urban realism. Burel used natural lighting for the street scenes, creating authentic shadows and contrasts that emphasized the harshness of Crainquebille's world. The camera work was notably mobile for its time, with tracking shots following Crainquebille through the Parisian streets, creating a sense of his isolation within the bustling city. The courtroom sequences used dramatic high-angle shots to emphasize the protagonist's powerlessness before the justice system. The film's visual style balanced documentary-like realism with expressive lighting, particularly in the scenes showing Crainquebille's descent into poverty. Burel's work influenced subsequent French cinematography in its approach to urban subjects and social themes.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations in French cinema. Its extensive use of location shooting in Paris was unusual for the period, requiring portable camera equipment and careful planning around urban obstacles. The film's lighting techniques, particularly the use of natural light for street scenes, demonstrated advanced understanding of cinematography for its time. The production employed early forms of matte painting to enhance the Parisian cityscapes. The film's editing rhythm, particularly in the courtroom sequence, showed sophisticated understanding of pacing and tension building. The sound design, while limited by silent film technology, used visual and rhythmic elements to create auditory associations, particularly in the scenes of street life.

Music

As a silent film, Crainquebille would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical score would have been provided by a theater organist or small orchestra, often using popular classical pieces adapted to match the film's emotional tone. No original composed score for the film survives from 1922. Modern restorations have been accompanied by newly composed scores, most notably a 1995 restoration featuring music by French composer Jean-Louis Fournier. The original theatrical experience likely included musical cues for dramatic moments, with somber pieces for Crainquebille's trials and lighter themes for his moments of connection with the young street urchin.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, dialogue was conveyed through intertitles. Key intertitles included: 'Forty years at the same cart, and now they tell me to move.' 'Justice is blind, but she is not deaf to the powerful.' 'In the street, we are all brothers in misery.' 'A man is not guilty until proven innocent - unless he is poor.' 'The law protects the rich and imprisons the poor.'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing Crainquebille's daily routine, establishing his forty-year dedication to his work. The confrontation with the police officer, where Crainquebille's dignity slowly erodes under unjust authority. The courtroom scene, shot from high angles to emphasize his powerlessness before the judicial system. The sequence where Crainquebille, now a broken man, wanders the streets he once knew as a respected vendor. The poignant moments between Crainquebille and the young street urchin, showing humanity's capacity for kindness amid suffering. The final scene where Crainquebille collapses in the street, surrounded by indifferent passersby, serving as the film's powerful social commentary.

Did You Know?

- The film was based on Anatole France's story which was itself inspired by the real-life Dreyfus Affair, making it politically charged material for its time.

- Maurice de Féraudy, who played Crainquebille, was 65 years old during filming and had been a renowned stage actor before transitioning to cinema.

- The young street urchin 'La Môme' was played by Jean Forest, who would become one of France's most famous child actors of the silent era.

- Director Jacques Feyder was Belgian by birth but became a naturalized French citizen and was instrumental in developing French cinematic realism.

- The film was initially banned in some conservative French regions due to its critical portrayal of police and the justice system.

- Anatole France, the original author, was alive during the film's production and reportedly approved of the adaptation.

- The film's title character's name 'Crainquebille' has since entered the French language as a term meaning someone who is unfairly victimized by authority.

- The production company Les Films Albatros was formed by Russian émigrés who had fled the revolution and brought their technical expertise to French cinema.

- The film was one of the first French productions to use authentic location shooting for urban scenes rather than relying entirely on studio sets.

- The police officer's uniform in the film was historically accurate to the period depicted, showing Feyder's attention to detail.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film's social consciousness and technical achievements. French newspaper Le Petit Parisien hailed it as 'a masterpiece of cinematic social commentary,' while British film journal Close Up called it 'a triumph of French cinematic art.' Modern critics have recognized the film as a pioneering work of social realism, with the Cinémathèque Française describing it as 'a crucial link between early French cinema and the poetic realist movement.' The film's emotional power and visual sophistication have been consistently noted, with particular praise for Maurice de Féraudy's performance. Some contemporary critics initially found the film's social critique too harsh, but over time it has come to be regarded as one of the most important French films of the 1920s.

What Audiences Thought

The film was a commercial success in France, particularly resonating with working-class audiences who identified with Crainquebille's struggle against authority. The film's release coincided with widespread public frustration with police practices, and many viewers saw their own experiences reflected in the story. The emotional connection between Crainquebille and the young street urchin particularly moved audiences, becoming one of the most discussed aspects of the film. The film's reputation grew through word-of-mouth, leading to extended runs in Parisian cinemas. International audiences also responded positively, with the film finding success in Belgium and Switzerland. However, some conservative viewers objected to what they perceived as the film's anti-authoritarian stance, leading to occasional protests outside theaters.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Works of Émile Zola

- German expressionist cinema

- Italian neorealism (precursor)

- Anatole France's literary realism

- French naturalist literature

- D.W. Griffith's social dramas

This Film Influenced

- The Lower Depths (1936)

- Les Misérables (1934)

- The Crime of Monsieur Lange (1936)

- La Grande Illusion (1937)

- Italian neorealist films of the 1940s

- The 400 Blows (1959)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved by the Cinémathèque Française. A restoration was completed in 1995 using surviving nitrate prints from various archives. While some scenes remain incomplete due to nitrate decomposition, the film is largely intact and viewable. The restoration work was part of a larger project to preserve French silent cinema classics. The film exists in both French and export versions with slight variations in editing. Digital copies are available for academic and archival purposes.