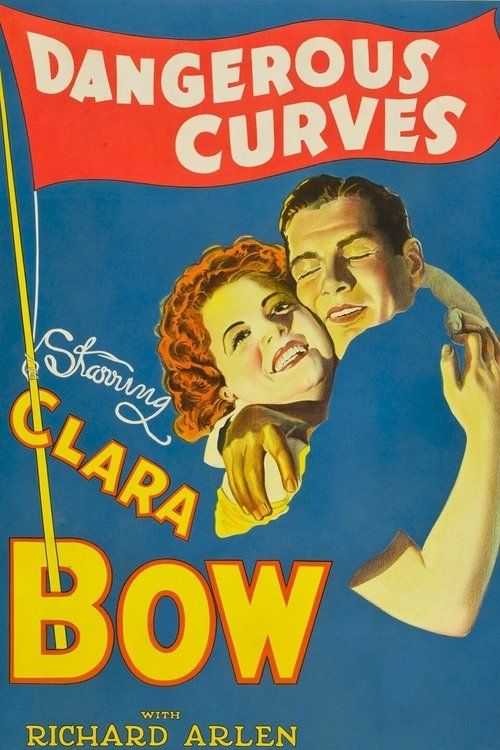

Dangerous Curves

"The 'It' Girl in the Most Thrilling Circus Drama Ever Filmed!"

Plot

Pat (Clara Bow) is a talented bareback rider in a traveling circus who is deeply in love with Larry (Richard Arlen), the show's star trapeze artist. However, Larry struggles with a severe drinking problem and becomes dangerously involved with Sally (Kay Francis), a manipulative circus performer who uses her feminine wiles to control him. As Larry's alcoholism worsens and his relationship with Sally intensifies, Pat desperately tries to save the man she loves from both his self-destructive habits and the predatory woman who threatens to ruin him completely. The film builds to a dramatic climax during a circus performance where all the emotional tensions explode, forcing Larry to confront his demons and choose between his destructive lifestyle and his genuine love for Pat.

About the Production

This was one of Clara Bow's first sound films, made during the challenging transition period from silent to talkies. The circus sequences required extensive preparation and coordination with real circus performers. The film was produced as a part-talkie, featuring both synchronized sound sequences and silent segments with musical accompaniment. Paramount invested significantly in the production due to Bow's star power and the public's fascination with circus-themed melodramas.

Historical Background

Dangerous Curves was produced during a pivotal moment in American cinema history - the transition from silent films to talkies. The year 1929 marked the complete dominance of sound in Hollywood, with studios scrambling to convert their silent stars and production techniques to accommodate the new technology. The film was released just months after the devastating stock market crash of October 1929, making it part of the last wave of films from the prosperous Jazz Age before the Great Depression fundamentally changed American entertainment. Circus films were particularly popular during this era, reflecting the public's fascination with spectacle and escapism during uncertain times. The film also represents the peak of Clara Bow's career before personal and professional challenges would diminish her star power in the early 1930s.

Why This Film Matters

As one of Clara Bow's early sound vehicles, 'Dangerous Curves' represents an important transitional artifact in Hollywood history. The film showcases how studios attempted to preserve the appeal of silent era stars while adapting to the demands of sound cinema. Bow's performance demonstrated that silent film stars could successfully make the transition, influencing how other studios approached similar conversions with their talent. The circus melodrama genre, exemplified by this film, reflected American society's fascination with entertainment and spectacle during the final years of the Roaring Twenties. The film's themes of addiction, manipulation, and redemption were particularly resonant during a period when America was about to face its own national crisis with the Great Depression.

Making Of

The production of 'Dangerous Curves' was fraught with the typical challenges of early sound filmmaking. The sound recording equipment was bulky and immobile, forcing the circus sequences to be filmed with limited camera movement. Clara Bow, who had become America's sweetheart through silent films, was notoriously anxious about the transition to sound, fearing her thick Brooklyn accent would alienate audiences. The studio invested heavily in voice coaching for her, and her performance was considered a success despite the technical limitations. The circus set was one of the most expensive built on the Paramount lot that year, requiring multiple cranes and safety equipment for the trapeze sequences. Richard Arlen, a former aviator and amateur athlete, insisted on performing many of his own stunts, much to the concern of the production crew. Kay Francis, playing the vamp, reportedly used method acting techniques that were unusual for the period, staying in character between takes and creating genuine tension with her co-stars.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Harry Fischbeck faced the technical constraints of early sound filming, with limited camera mobility due to sound recording equipment. The circus sequences, however, showcase impressive technical achievements for the period, including dramatic high-angle shots of the trapeze performances and close-ups that capture the emotional intensity of the performers. The film uses lighting techniques inherited from silent cinema, particularly in the dramatic scenes between Bow and Francis, creating stark contrasts that emphasize the moral conflict at the story's core. The visual style maintains the dramatic lighting of late silent films while accommodating the new requirements of sound recording.

Innovations

Dangerous Curves utilized the Movietone sound-on-film system, representing one of the early successful implementations of synchronized sound in feature films. The production pioneered techniques for filming action sequences with sound equipment, developing methods to minimize camera noise while capturing dynamic circus performances. The film's trapeze sequences required innovative camera rigging to capture aerial movements while maintaining sound quality. The blending of silent and sound sequences demonstrated transitional techniques that would become standard in early talkie productions. The film also showcased early attempts at location-style sound recording within studio sets, creating more authentic audio environments for the circus atmosphere.

Music

The film featured a synchronized musical score composed by John Leipold, with sound effects and dialogue sequences typical of early part-talkie productions. The music incorporated popular circus themes and melodies of the era, enhancing the spectacle of the performance sequences. The sound quality reflects the technological limitations of 1929, with noticeable audio hiss and limited dynamic range. The film used the Movietone sound system, which was Paramount's preferred technology for early sound productions. Musical accompaniment was provided by the Paramount studio orchestra, creating a rich soundscape that attempted to compensate for the visual limitations imposed by early sound recording equipment.

Famous Quotes

Pat: 'You're killing yourself with that stuff, Larry! Can't you see what she's doing to you?'

Sally: 'Men are like trapeze artists - they're always reaching for something just beyond their grasp.'

Larry: 'The circus is all I know, Pat. It's in my blood.'

Ringmaster: 'The show must go on! No matter what happens behind the curtain!'

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic trapeze sequence where Larry must perform while intoxicated, creating genuine tension as he nearly falls multiple times before Pat's encouragement helps him complete the death-defying act. The scene combines spectacular circus performance with emotional drama, showcasing both the technical achievements of early sound filming and the powerful chemistry between the leads.

Did You Know?

- This was Clara Bow's first sound film with Paramount Pictures, marking a crucial transition in her career from silent superstardom to talkies.

- The film was released just months after the stock market crash of 1929, making it one of the last films of the roaring twenties era.

- Circus sequences were filmed with the assistance of the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus performers.

- Kay Francis, who played the vamp, was relatively unknown at the time but would become one of Warner Bros.' biggest stars in the 1930s.

- The film featured synchronized sound sequences but was primarily shot as a silent film with added music and sound effects, typical of early transitional productions.

- Richard Arlen performed many of his own trapeze stunts, though dangerous sequences were handled by professional circus artists.

- The original working title was 'Circus Girl' before being changed to the more provocative 'Dangerous Curves'.

- Clara Bow's Brooklyn accent was initially considered a liability for sound films, but Paramount invested in diction coaching for this production.

- The film's circus setting was constructed entirely on the Paramount backlot, costing approximately $50,000 for the elaborate set.

- This was one of the last films directed by Lothar Mendes before he left Paramount for other studios.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics were generally positive about Clara Bow's transition to sound, praising her natural screen presence and noting that her distinctive voice added authenticity to her character. Variety noted that 'Miss Bow handles her dialogue with surprising ease and her emotional scenes carry the same impact they did in her silent pictures.' The New York Times commented on the film's spectacular circus sequences while finding the plot somewhat conventional. Modern critics view the film as an interesting example of early sound cinema, appreciating its historical significance while acknowledging the technical limitations of the period. The film is often cited in film studies courses as an example of how studios navigated the challenging transition from silent to sound films.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1929 were eager to see Clara Bow speak on screen for the first time, and the film performed respectably at the box office despite the economic uncertainties following the stock market crash. Bow's fans were relieved that her distinctive voice and personality translated well to sound, and many contemporary accounts mention enthusiastic audience reactions during her scenes. The circus spectacle elements were particularly popular with audiences seeking entertainment and escapism during increasingly difficult economic times. However, the film's commercial performance was ultimately impacted by the worsening Depression, which dramatically reduced movie attendance across the country in late 1929.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Circus (1928) by Charlie Chaplin

- Sadie Thompson (1928)

- The Docks of New York (1928)

- The Wind (1928)

- Our Dancing Daughters (1928)

This Film Influenced

- Murder at the Vanities (1934)

- The Big Show (1936)

- The Greatest Show on Earth (1952)

- Trapeze (1956)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in complete form with both picture and sound elements intact. A 35mm nitrate print is preserved at the Library of Congress, and the film has been transferred to safety stock. The UCLA Film and Television Archive also holds preservation materials. While not widely available on home video, the film occasionally screens at classic film festivals and archives specializing in early cinema. The sound elements show some deterioration typical of early talkie recordings but remain audible and comprehensible.