Didone abbandonata

Plot

After seven years of wandering following the fall of Troy, Aeneas and his fellow Trojans encounter a violent storm that shipwrecks them on the African coast near Carthage. The shipwrecked survivors are discovered by the Amazons, who lead them to Queen Dido of Carthage, who immediately falls deeply in love with the heroic Aeneas upon their meeting. Their romance blossoms until the King of Numidia, Iarbas, arrives seeking Dido's hand in marriage, but she firmly rejects him in favor of Aeneas. However, divine intervention occurs when Aeneas's deceased father Anchises appears to him in a dream, commanding him to leave Carthage to fulfill his destiny of founding Rome. While Iarbas's army surrounds the city in retaliation for Dido's rejection, Aeneas secretly embarks with his men, leaving behind a heartbroken and devastated Dido who ultimately takes her own life in despair.

About the Production

This film was produced during the golden age of Italian cinema, when Ambrosio Film was one of Europe's most prestigious production companies. The production utilized elaborate sets and costumes typical of the historical epics that Italian cinema was famous for during this period. The film employed hundreds of extras for the battle scenes and court sequences, demonstrating the scale of Italian productions even in this early era of cinema.

Historical Background

1910 was a pivotal year in cinema history, occurring during the transition from short films to longer narrative features. Italian cinema was experiencing its first golden age, with studios like Ambrosio Film leading the world in production quality and ambition. The country was leveraging its classical heritage and Roman history to create spectacular historical epics that appealed to international audiences. This period also saw the rise of the 'diva' film in Italy, featuring strong female protagonists in dramatic roles. The film industry was becoming increasingly professionalized, with dedicated studios, specialized technicians, and recognizable stars. Internationally, cinema was transitioning from novelty to art form, with longer running times and more complex narratives becoming standard.

Why This Film Matters

'Didone abbandonata' represents an important early example of literary adaptation in cinema, demonstrating how filmmakers were already recognizing the potential of classical literature for dramatic storytelling. The film contributed to establishing Italy's reputation for producing grand historical epics, a tradition that would continue through the silent era and beyond. As one of the earliest treatments of the Dido and Aeneas story on film, it helped establish visual conventions for depicting classical mythology that would influence later adaptations. The film also exemplifies the early 20th century fascination with classical antiquity, reflecting how cinema was becoming a new medium for retelling timeless stories. Its existence shows that even in cinema's infancy, filmmakers were tackling complex emotional themes and tragic narratives.

Making Of

The production of 'Didone abbandonata' took place during a remarkable period in Italian cinema when the country was producing some of the most ambitious films in the world. Director Luigi Maggi, who had previously worked as an actor, brought theatrical experience to the film's staging. The production required extensive sets representing ancient Carthage, which were built in Ambrosio Film's studios in Turin. The storm sequence was achieved using primitive special effects techniques including water tanks, wind machines, and camera tricks. The large number of extras required for the court scenes and battle sequences demonstrated the scale of Italian productions even in these early years. The actors, trained in theatrical tradition, used exaggerated gestures and expressions typical of silent film acting to convey emotions without dialogue.

Visual Style

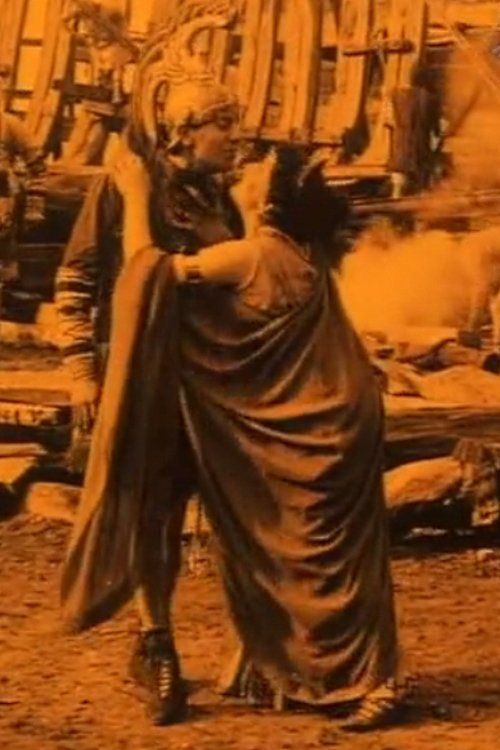

The cinematography, while limited by 1910 technology, employed several innovative techniques for its time. The film used multiple camera setups to vary the visual narrative, including close-ups for emotional moments and wide shots for the spectacular sequences. The storm scene utilized camera movement and special effects to create the illusion of a violent sea. The lighting techniques, though primitive, attempted to create dramatic contrasts between scenes, particularly in the dream sequence with Anchises. The film likely employed the common practice of scene tinting, with different colors used to establish mood and time of day. The composition of shots showed the influence of theatrical staging, with careful attention to the placement of actors within the elaborate sets.

Innovations

For its time, the film demonstrated several technical achievements in early cinema. The production utilized large-scale set construction that was ambitious for 1910, creating convincing representations of ancient Carthage. The storm sequence employed early special effects techniques including water tanks, wind machines, and camera tricks to simulate the shipwreck. The film's use of multiple locations and complex scene changes showed advances in editing and narrative structure. The production also demonstrated sophisticated costume design and makeup techniques for creating the appearance of ancient characters. The film's relatively long running time for the period (approximately 15-20 minutes) required advances in film stock and projection technology, contributing to the development of the feature film format.

Music

As a silent film, 'Didone abbandonata' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its theatrical run. The typical accompaniment would have been a pianist or small ensemble playing classical pieces appropriate to the film's classical setting. Music selections likely included works by composers like Wagner, whose operatic themes matched the film's dramatic tone, and Italian classical composers. The musical score would have been cued to the film's action, with romantic themes for the love scenes between Dido and Aeneas, dramatic music for the storm and battle sequences, and mournful music for Dido's tragic end. Some theaters might have used compiled cue sheets specifically created for the film, while others relied on the musicians' improvisation skills.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, dialogue was conveyed through intertitles and acting, with key emotional moments expressed through gestures and visual storytelling rather than spoken words

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic storm sequence that shipwrecks the Trojans, utilizing early special effects to create a violent sea

- The first meeting between Dido and Aeneas in the Carthaginian court, showcasing the elaborate sets and costumes

- The dream sequence where Anchises appears to Aeneas, using supernatural lighting effects

- Dido's tragic suicide scene, considered one of the most powerful moments in early Italian cinema

- The secret embarkation of Aeneas while Iarbas's army surrounds Carthage, creating dramatic tension

Did You Know?

- This is one of the earliest film adaptations of Virgil's Aeneid, specifically focusing on the Dido episode from Books 1-4

- The film was part of a wave of classical adaptations that dominated early Italian cinema, capitalizing on the country's Roman heritage

- Director Luigi Maggi was one of Italy's pioneering filmmakers, having started his career as an actor before moving behind the camera

- The film was produced by Ambrosio Film, which was founded in 1906 and became one of the most important European film companies of the silent era

- Like many films of this era, it was likely tinted by hand - blue for night scenes, amber for daylight, and red for dramatic moments like Dido's death

- The role of Dido was played by Mirra Principi, one of the few early Italian actresses known by name, as most performers were not credited

- The film would have been accompanied by live musical accompaniment, typically a pianist or small orchestra playing classical pieces

- This adaptation predates the more famous 1924 Italian epic 'Cabiria' by four years, but shares similar grandiose production values

- The film was distributed internationally, helping establish Italy's reputation for producing lavish historical epics

- Original intertitles would have been in Italian, with translations made for international releases

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film's lavish production values and ambitious scope, noting particularly the elaborate sets and costumes that brought ancient Carthage to life. Reviews in Italian film journals highlighted the dramatic performance of Mirra Principi as Dido and the effective staging of the storm sequence. International critics, particularly in France and England, commented on Italy's growing reputation for producing spectacular historical films. Modern film historians view the work as an important example of early Italian cinema's artistic ambitions, though they note the limitations of 1910 filmmaking technology in conveying the full emotional depth of the classical source material.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1910 reportedly responded enthusiastically to the film's dramatic story and visual spectacle. The tragic romance of Dido and Aeneas resonated with viewers familiar with the classical story, while those new to the tale were captivated by the emotional drama. The film's success in Italy and abroad helped establish the market for longer narrative features and contributed to the growing popularity of historical epics. Contemporary accounts suggest that audiences were particularly moved by Dido's suicide scene, which was considered one of the most powerful moments in early cinema. The film's commercial success encouraged Ambrosio Film and other Italian studios to produce more ambitious literary and historical adaptations.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Virgil's Aeneid

- Classical Roman mythology

- Italian opera tradition

- 19th century theatrical productions

- Earlier historical paintings of classical subjects

This Film Influenced

- Later adaptations of the Aeneid

- Italian historical epics of the 1910s-1920s

- The development of the costume drama genre

- Subsequent treatments of classical mythology in cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Like many films from 1910, 'Didone abbandonata' is considered partially lost or in fragmentary condition. Some sources suggest that portions of the film may exist in European film archives, particularly in Italy's Cineteca Nazionale, but a complete version is not known to survive. This is typical for films of this era, as the unstable nitrate film stock and lack of systematic preservation efforts led to the loss of the majority of early cinema works. Some still photographs and production documentation may survive in historical archives.