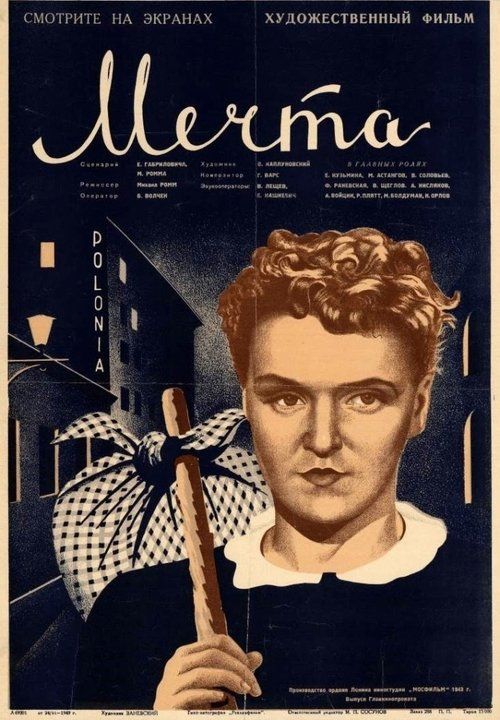

Dream

"Where dreams go to die in the city of broken promises"

Plot

In this poignant Soviet drama, young Anna leaves her Ukrainian village with dreams of a better life in the big city, full of hope and ambition. Three years later, her dreams have been crushed by the harsh realities of urban life, as she finds herself working two menial jobs just to survive in a cramped rooming house. The film follows Anna's daily struggles alongside other broken souls who inhabit the same boarding house, each with their own shattered dreams and desperate circumstances. Through Anna's experiences, the film explores the gap between youthful aspirations and adult disillusionment in pre-war Soviet society. The narrative builds to a powerful climax where Anna must confront whether to continue fighting for her dreams or surrender to the crushing weight of her circumstances. The film serves as both a personal tragedy and a broader commentary on the human cost of industrialization and urban migration in the Soviet Union.

About the Production

Filmed during a critical period just before the Soviet Union's entry into World War II, the production faced increasing resource constraints as the country prepared for war. The film's realistic depiction of urban poverty and disillusionment was somewhat daring for the time, though it still operated within the boundaries of Soviet socialist realism. Director Mikhail Romm was known for his meticulous attention to detail and demanded extensive rehearsals from his cast, particularly for the emotionally intense scenes in the rooming house. The film's production was rushed to completion before the German invasion in June 1941, which would have halted production entirely.

Historical Background

The film was produced and released in 1941, a pivotal year in Soviet and world history. The Soviet Union was in a precarious position, having signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with Nazi Germany in 1939, which gave the USSR time to prepare for what many expected to be an inevitable conflict. The country was still recovering from the Great Purge of 1937-1938, which had decimated the military, political, and cultural elite. Industrialization was continuing at a rapid pace, with millions of peasants migrating to cities for work in new factories, often finding conditions harsher than promised. The film's focus on urban disillusionment reflected growing concerns about the human cost of rapid industrialization. Just three months after the film's release, Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, fundamentally changing the country's priorities and cinematic output. The timing makes 'Dream' particularly significant as one of the last Soviet films to address social issues before the total focus shifted to wartime propaganda and patriotic films.

Why This Film Matters

'Dream' represents an important transitional moment in Soviet cinema, bridging the gap between the optimistic socialist realism of the 1930s and the wartime cinema that would follow. The film's willingness to acknowledge the darker side of Soviet urban life, however subtly, marked a significant departure from the typical heroic narratives of the period. It influenced subsequent Soviet filmmakers by demonstrating that it was possible to address social problems within the constraints of the system. The film also preserved a crucial record of pre-war Soviet urban life, capturing the atmosphere of boarding houses and the struggles of internal migrants. Its examination of the gap between dreams and reality resonated with Soviet audiences who had experienced similar disillusionments. The film's nuanced approach to social criticism, avoiding direct condemnation while still acknowledging problems, became a model for later Soviet filmmakers working under strict censorship. Today, 'Dream' is studied as an example of how Soviet artists managed to create meaningful art within ideological constraints, and as a valuable historical document of the final months of peace before the cataclysm of World War II.

Making Of

The production of 'Dream' took place during a tense period in Soviet history, as the country was still recovering from Stalin's purges while preparing for the inevitable conflict with Nazi Germany. Director Mikhail Romm, who had gained favor with the Soviet establishment for his Lenin films, used his reputation to push for more realistic storytelling. The casting process was particularly challenging, as Romm sought actors who could convey the deep disillusionment of their characters without appearing to criticize Soviet society directly. Yelena Kuzmina, who played Anna, underwent extensive preparation, spending time in actual Moscow rooming houses to observe the inhabitants and their daily routines. The film's most difficult scenes involved the crowded rooming house sequences, which required complex choreography and lighting to create the claustrophobic atmosphere. Romm insisted on multiple takes to capture the authentic sense of desperation and resignation among the characters. The production team faced increasing pressure from studio officials to make the film more optimistic, but Romm managed to maintain the story's bleak integrity, arguing that it served as a warning about the dangers of abandoning one's roots for false promises of urban prosperity.

Visual Style

The film's visual style, crafted by cinematographer Boris Volchek, employs a gritty realism that was innovative for Soviet cinema of the period. Volchek uses chiaroscuro lighting to emphasize the claustrophobic atmosphere of the rooming house, creating deep shadows that mirror the characters' psychological states. The camera work alternates between intimate close-ups that capture the characters' despair and wider shots that emphasize their isolation within the crowded urban environment. Volchek's use of deep focus allows multiple characters to remain visible in the frame simultaneously, reinforcing the theme of shared suffering. The film's visual palette deliberately shifts from the hopeful brightness of Anna's village memories to the muted grays and browns of her urban reality. The boarding house sequences feature complex tracking shots that follow characters through cramped corridors, creating a sense of entrapment. Volchek's innovative use of natural light, particularly in scenes shot through windows, adds to the documentary-like feel of the film. The cinematography avoids the heroic angles typical of socialist realism in favor of more human-scale perspectives that emphasize vulnerability rather than strength.

Innovations

The film showcased several technical innovations that were advanced for Soviet cinema in 1941. The production team developed new techniques for creating realistic urban interiors on studio sets, using forced perspective and carefully detailed props to achieve convincing depth. The lighting system for the boarding house scenes was particularly sophisticated, employing multiple light sources to simulate the harsh reality of shared living spaces. The film's sound recording equipment was modified to capture the subtle ambient noises of the boarding house environment, creating a more immersive audio experience. The makeup department developed new techniques for showing the physical toll of poverty and exhaustion on the characters' faces. The film's editing, supervised by Romm himself, employed innovative cross-cutting between Anna's present reality and her memories of village life, creating psychological depth. The production team also pioneered new methods for simulating urban weather conditions, including artificial rain and fog that could be controlled precisely for each take. The film's camera movement system allowed for unusually smooth tracking shots in the confined space of the boarding house set. These technical achievements contributed significantly to the film's realistic atmosphere and emotional impact, setting new standards for Soviet cinema production values.

Music

The musical score for 'Dream' was composed by Dmitri Kabalevsky, one of the most prominent Soviet composers of the period. Kabalevsky's music reflects the film's emotional journey, beginning with optimistic folk-inspired themes that represent Anna's dreams and gradually transitioning to more somber, dissonant passages as her hopes fade. The score makes subtle use of Ukrainian folk melodies, connecting Anna to her rural origins and emphasizing what she has lost in the city. Kabalevsky employs a reduced orchestra for many scenes, creating an intimate sound that matches the film's focus on individual suffering. The music often serves as a counterpoint to the visuals, with beautiful melodies accompanying bleak imagery to create emotional tension. The film's theme music, a haunting minor-key melody, recurs throughout the score, evolving as Anna's character develops. Sound design in the film is particularly effective in the boarding house scenes, where overlapping conversations, creaking floors, and distant city noises create an immersive atmosphere. The film's use of silence is equally powerful, with several key scenes featuring no music at all, allowing the raw emotions of the performances to dominate. The soundtrack was recorded using the latest Soviet audio technology of the time, resulting in unusually clear sound quality for the period.

Famous Quotes

In the city, dreams are like candles - they burn bright for a moment, then the darkness swallows them whole.

We came here looking for heaven, but found only different kinds of hell.

Sometimes the hardest work is not what you do with your hands, but what you do with your heart.

In this house, we are all ghosts of the people we meant to be.

The city promises everything, but the price is everything you were.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where young Anna leaves her village, filled with hope and carrying a small suitcase, waving goodbye to her family as the train pulls away - the bright, hopeful cinematography contrasts sharply with the rest of the film

- The powerful montage showing Anna working two different jobs - cleaning offices by night and washing dishes by day - intercut with her increasingly exhausted reflection in various mirrors

- The climactic scene in the rooming house where all the tenants gather in the common room, each sharing their broken dreams while a storm rages outside, creating a symphony of shared despair

- The heartbreaking moment when Anna receives a letter from home and realizes she can never return to her village, as she has become too changed by the city

- The final shot of Anna looking out her window at the dawn, her face illuminated by the first light, suggesting both resignation and a glimmer of renewed determination

Did You Know?

- The film was released just three months before the German invasion of the Soviet Union, making it one of the last pre-war Soviet dramas

- Director Mikhail Romm was already an established figure in Soviet cinema, having directed the acclaimed 'Lenin in October' (1937) and 'Lenin in 1918' (1939)

- Faina Ranevskaya, who played a supporting role, would become one of the most celebrated actresses in Soviet cinema history

- The film's realistic depiction of urban poverty was unusual for Soviet cinema of the period, which typically focused on heroic workers and collective farmers

- The rooming house set was so meticulously detailed that it reportedly took weeks to construct, with each room having its own distinct character and backstory

- The film was briefly withdrawn from circulation after the German invasion, as authorities felt its pessimistic tone was inappropriate for wartime audiences

- Yelena Kuzmina's performance was particularly praised for its naturalism, a style that was becoming more accepted in Soviet cinema of the late 1930s

- The film's original title was 'The Broken Dream' but was shortened to simply 'Dream' by studio executives

- Despite being made during the Stalin era, the film contains subtle criticism of the promises of Soviet industrialization

- The cinematographer, Boris Volchek, would later become one of the most respected cinematographers in Soviet film history

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film for its artistic merit and emotional depth, though some noted its unusually pessimistic tone. Pravda, the official newspaper of the Communist Party, gave the film a positive review, highlighting Yelena Kuzmina's powerful performance and Romm's sensitive direction. However, some critics expressed concern that the film's bleak outlook might undermine Soviet morale during a time of international tension. Western critics had limited opportunity to see the film due to wartime restrictions, but those who did viewed it as evidence of growing sophistication in Soviet cinema. In later years, film historians have reevaluated 'Dream' as a significant work that managed to transcend its ideological constraints. Modern critics appreciate the film's technical achievements, particularly Boris Volchek's cinematography and the detailed production design. The film is now recognized as an important example of pre-war Soviet cinema that dared to address social problems with nuance and complexity. Many contemporary scholars view it as one of Mikhail Romm's most personal and artistically successful works, demonstrating his ability to work within the system while still creating meaningful cinema.

What Audiences Thought

Soviet audiences in 1941 responded positively to the film's emotional honesty and relatable characters. Many viewers identified with Anna's struggle to maintain hope in difficult circumstances, reflecting widespread experiences of urban migration and disappointment. The film's realistic depiction of boarding house life resonated with the millions of Soviet citizens living in similar conditions. However, some audience members found the film's ending too bleak, particularly as tensions with Germany were rising. After the German invasion, the film was briefly pulled from theaters as authorities feared its pessimistic tone might harm morale. In the post-war period, 'Dream' developed a cult following among Soviet cinema enthusiasts who appreciated its artistic courage and technical excellence. The film gained new appreciation during the Khrushchev Thaw, when its subtle social criticism could be more openly acknowledged. Modern Russian audiences continue to discover the film through retrospectives and film festivals, where it is often praised for its timeless themes and artistic integrity. The performances, particularly by Yelena Kuzmina and Faina Ranevskaya, remain celebrated by film lovers and are frequently cited as examples of the golden age of Soviet acting.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize, Second Class (1941) - awarded to director Mikhail Romm

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Soviet socialist realism (subverted)

- Italian neorealism (precursor)

- German expressionist lighting techniques

- French poetic realism

- John Ford's visual storytelling

- Eisenstein's montage theory (adapted)

This Film Influenced

- The Cranes Are Flying (1957)

- Ballad of a Soldier (1959)

- Ivan's Childhood (1962)

- The Ascent (1977)

- Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears (1980)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The original negative of 'Dream' was preserved in the Gosfilmofond archive in Moscow, though it suffered some damage during the war years. A complete restoration was undertaken in the 1970s by Mosfilm, which included cleaning and repairing the original elements. A digital restoration was completed in 2015 as part of a broader project to preserve classic Soviet cinema. The restored version premiered at the Moscow International Film Festival and has since been shown at various classic film retrospectives worldwide. The film is considered well-preserved compared to other Soviet films from the same period, partly due to its cultural significance and the care taken by Soviet archives to protect works by prominent directors like Mikhail Romm. Some minor damage remains visible in certain scenes, but this does not significantly impact viewing experience. The restored version includes improved sound quality, with much of the original audio track cleaned of age-related deterioration.