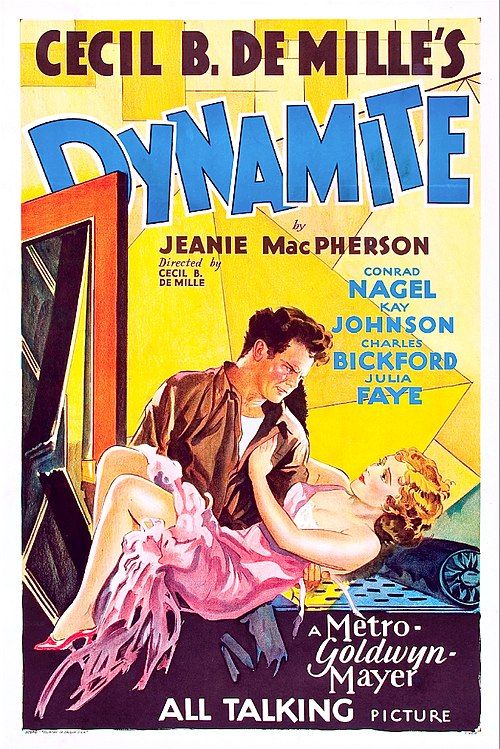

Dynamite

"A Dynamite Picture! Cecil B. DeMille's Master Production of Human Explosions!"

Plot

Wealthy socialite Cynthia Crothers is deeply in love with Roger Towne, a man trapped in a loveless marriage with Marcia. In a remarkably modern arrangement, Marcia agrees to divorce Roger if Cynthia provides a substantial financial settlement. However, Cynthia faces a crisis: her trust fund will expire unless she marries before her upcoming birthday. Desperate to maintain her wealth and independence, Cynthia arranges a marriage of convenience with Hagon Derk, a condemned prisoner scheduled to die for a murder he didn't commit. She pays him handsomely so he can provide for his young sister after his execution. In a dramatic twist, the real murderer confesses at the last minute, freeing Derk just as he's about to be executed. Cynthia, who expected to become a wealthy widow, suddenly finds herself legally married to a man she barely knows and doesn't want, leading to complications as Roger still pursues her and Derk develops genuine feelings for his unexpected wife.

About the Production

Dynamite was one of Cecil B. DeMille's first all-talking pictures, filmed during the challenging transition from silent to sound cinema. The production utilized early sound recording equipment that was cumbersome and restrictive for actors' movements. DeMille, known for his elaborate productions, had to adapt his directing style to accommodate the technical limitations of early sound recording. The prison scenes were particularly challenging to film with sound equipment, requiring innovative microphone placement. The film featured both synchronized dialogue and musical sequences, showcasing MGM's commitment to the new sound technology.

Historical Background

Dynamite was produced during a pivotal moment in Hollywood history - the transition from silent to sound cinema. Released in October 1929, it premiered just weeks before the devastating stock market crash that would usher in the Great Depression. The film reflects the sophisticated, modern attitudes of the late 1920s Jazz Age, with its frank discussion of divorce, extramarital affairs, and financial arrangements. This period saw Hollywood grappling with new censorship challenges as sound made dialogue more explicit and controversial. The film's themes of financial desperation and arranged marriage resonated deeply with audiences facing economic uncertainty. DeMille, a master of both silent and sound cinema, used this film to demonstrate his adaptability to the new medium while maintaining his signature blend of melodrama and spectacle.

Why This Film Matters

Dynamite represents an important transitional work in American cinema, showcasing how one of Hollywood's most successful silent directors adapted to the sound era. The film's sophisticated treatment of adult themes, including divorce, financial transactions in marriage, and complex romantic entanglements, pushed boundaries for what was acceptable in mainstream cinema. Its success helped establish the viability of dramatic talkies beyond musicals and comedies. The film's frank discussion of women's financial independence and agency in relationships reflected changing social attitudes in the late 1920s. Additionally, its Academy Awards recognition helped establish the prestige of the newly created awards ceremony and demonstrated that sound films could achieve artistic merit equal to their silent predecessors.

Making Of

The production of Dynamite was fraught with the typical challenges of early sound filming. Actors were confined to small areas around hidden microphones, limiting DeMille's trademark sweeping camera movements. The director famously complained about the restrictions but adapted by focusing more on intimate close-ups and dialogue-driven scenes. The prison sequence required special soundproofing to eliminate echo, and the execution chamber scene was filmed in a specially constructed set. DeMille clashed with MGM executives over the film's adult themes and controversial subject matter, but ultimately won most battles due to his star power. The film's score was composed by William Axt and included several original songs performed on screen, a novelty in early talkies.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Harold Rosson and Peverell Marley demonstrated the challenges and innovations of early sound filming. The camera work was necessarily more static than in DeMille's silent epics due to microphone placement restrictions, but the cinematographers compensated with creative lighting and composition. The prison sequences utilized dramatic high-contrast lighting to create a somber, oppressive atmosphere. The film employed extensive close-ups to take advantage of the new sound technology and capture the actors' performances. The execution chamber scene featured particularly innovative use of shadows and camera angles to build tension while working within sound recording limitations.

Innovations

Dynamite showcased several technical innovations in early sound cinema. The film utilized the Western Electric sound-on-disc system, which was considered state-of-the-art in 1929. The production team developed innovative microphone concealment techniques to allow for more natural actor movement. The prison execution sequence featured synchronized sound effects that were remarkably realistic for the period. The film's sound mixing demonstrated early sophistication in balancing dialogue, music, and effects. MGM invested heavily in soundproofing sets and developing directional microphones to improve audio quality. The technical achievements of Dynamite helped establish standards for sound recording in dramatic films.

Music

The musical score for Dynamite was composed by William Axt, one of MGM's top composers during the transition to sound. The film featured both background music and several musical numbers performed on screen by the characters. The soundtrack included original songs such as 'Dynamite' and 'You're the One for Me,' which were published as sheet music to promote the film. The score utilized the full capabilities of the early sound system, with synchronized sound effects and dialogue. The prison scenes featured minimal music to enhance the dramatic tension, while the romantic scenes were accompanied by lush orchestral arrangements typical of late 1920s melodramas.

Did You Know?

- This was Cecil B. DeMille's first all-talking film, though he had previously made part-talkies

- Kay Johnson made her film debut in this movie and married director John Cromwell the same year

- The film was originally conceived as a silent picture but was converted to sound during production

- Charles Bickford was reportedly difficult on set, often clashing with DeMille over his character's motivations

- The prison execution sequence was considered unusually graphic and realistic for its time

- DeMille paid $25,000 for the film rights to the story, a substantial sum in 1929

- The film's title 'Dynamite' refers both to explosive situations and the literal dynamite used in the story

- MGM marketed the film heavily as 'DeMille's First All-Talking Masterpiece'

- The movie was released just weeks before the stock market crash of 1929, affecting its box office performance

- Conrad Nagel was one of the few silent stars who successfully transitioned to talkies

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Dynamite for its bold storytelling and successful transition to sound. The New York Times hailed it as 'a triumph of the talking picture' and particularly commended DeMille's handling of the new medium. Variety noted that 'DeMille has lost none of his punch in the transition to sound' and praised the performances, especially Kay Johnson's screen debut. Modern critics view the film as an important historical document of early sound cinema, with its mixture of sophisticated themes and sometimes awkward technical execution. The film is now recognized as a significant work in DeMille's filmography, demonstrating his ability to adapt to changing cinematic technologies while maintaining his distinctive directorial style.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1929 responded positively to Dynamite's dramatic story and the novelty of hearing their favorite stars speak. The film's adult themes and sophisticated plot appealed to urban audiences seeking more mature entertainment options. Despite opening strongly, the film's box office performance was ultimately affected by the stock market crash that occurred shortly after its release. However, it still managed to turn a profit for MGM and cemented DeMille's reputation as a director who could successfully navigate the transition to sound. The film's success helped prove that dramatic, non-musical talkies could be commercially viable, encouraging other studios to invest in similar productions.

Awards & Recognition

- Academy Award for Best Writing (Original Story) - Howard Estabrook (WINNER)

- Academy Award for Best Art Direction (WINNER)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Jazz Age culture of the 1920s

- Early sound film techniques from 'The Jazz Singer' (1927)

- Broadway melodramas of the 1920s

- DeMille's own silent epics and moral tales

- Contemporary newspaper stories about wrongful convictions

This Film Influenced

- Madam Satan

- 1930

- also by DeMille)

- The Divorcee

- 1930

- ,

- Other Men's Women

- 1931

- ,

- The Story of Temple Drake

- 1933

- ],

- similarFilms

- The Divorcee,1930,,,The Cheat,1931,,,The Easiest Way,1931,,,Merrily We Go to Hell,1932,,,The Mouthpiece,1932,],,famousQuotes,Cynthia: 'I'm not afraid of marriage. I'm afraid of being poor.',Hagon: 'A man's life is worth more than money, even if it's only borrowed time.',Marcia: 'In this modern world, we must be practical about our emotions.',Roger: 'Love and money have always been the same thing, haven't they?',Cynthia: 'I bought a husband, but I didn't bargain for a conscience.',memorableScenes,The tense prison execution sequence where Hagon Derk awaits his fate at the gallows, only to be saved at the last minute by a telegram revealing the true murderer's confession,The sophisticated cocktail party scene where Cynthia, Roger, and Marcia openly discuss their romantic arrangement with shocking modernity,The courtroom scene where the real murderer dramatically confesses, creating chaos and overturning Derk's conviction,The awkward wedding ceremony between Cynthia and the condemned Derk, filled with unspoken tension and irony,The final confrontation scene where all three main characters face the consequences of their arrangements and choices,preservationStatus,Dynamite is preserved in the MGM/United Artists film archive and has been restored by Warner Bros. (current owner of MGM's library). A complete 35mm print exists in the UCLA Film and Television Archive. The film was released on DVD as part of the Warner Archive Collection in 2010, featuring a restored print with improved audio quality. While some early sound films have been lost due to the decomposition of nitrate stock, Dynamite survived in relatively good condition, likely due to its Academy Award wins and subsequent preservation efforts.,whereToWatch,Warner Archive DVD (manufactured on demand),Classic film streaming services (availability varies),Film archives and special screenings,TCM (Turner Classic Movies) occasional broadcasts,Public domain status: NOT in public domain - owned by Warner Bros.