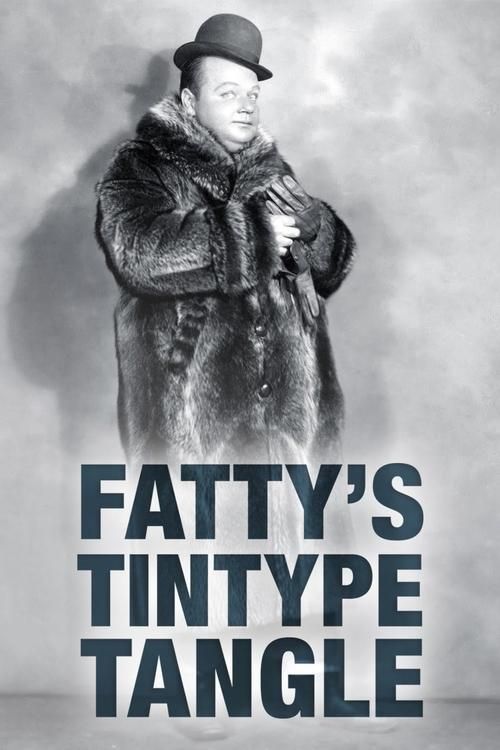

Fatty's Tintype Tangle

Plot

In this classic Keystone comedy, Fatty plays a henpecked husband whose wife's mother constantly berates him. After gaining Dutch courage from a nip of whiskey, he storms out declaring he won't be a domestic slave anymore. He heads to a park where a photographer mistakes him for a seated woman's sweetheart and takes a tintype of them together. When the woman's jealous husband discovers this photograph, Fatty flees town, telling his wife he's going on business. Unbeknownst to him, his wife moves in with her mother and rents their house to the very couple from the park. When Fatty returns home unexpectedly, he finds himself in another tangle of jealousy and mistaken identity.

About the Production

This film was part of Arbuckle's prolific 1915 output at Keystone, where he was directing and starring in multiple shorts per month. The tintype prop was a common photographic method of the era, adding authenticity to the mistaken identity premise. The park scenes were likely filmed at nearby Echo Park or Griffith Park, common Keystone locations.

Historical Background

1915 was a pivotal year in cinema history. The feature film 'The Birth of a Nation' had just revolutionized filmmaking techniques, while comedy shorts remained the bread and butter of most theaters. World War I was raging in Europe, though America remained neutral, making escapist entertainment like Arbuckle's comedies increasingly popular. The film industry was consolidating in Hollywood, with Keystone Studios being one of the most successful comedy producers. This period saw the transition from short one-reelers to longer multi-reel films, though Arbuckle continued to excel in the short format. The era's rapid technological changes, including the widespread adoption of electric lighting in studios, were transforming what was possible in film production.

Why This Film Matters

Fatty's Tintype Tangle represents the peak of the Keystone comedy style that defined American humor in the 1910s. Arbuckle's character challenged traditional notions of masculinity, using his size for both comedic effect and as a subversion of leading man stereotypes. The film's exploration of domestic relationships and jealousy reflected changing social attitudes toward marriage and gender roles. As part of Arbuckle's extensive body of work, it contributed to the development of American comedy cinema, influencing countless comedians who followed. The mistaken identity trope would become a staple of comedy films throughout cinema history, with this film being an early example of its effective use in visual storytelling.

Making Of

Roscoe 'Fatty' Arbuckle was at the height of his creative powers in 1915, having complete creative control over his films at Keystone. The studio's famous 'anything goes' approach to comedy allowed Arbuckle to experiment with physical gags and situational comedy. The tintype sequence required careful staging to ensure the mistaken identity premise worked visually. Arbuckle was known for his collaborative directing style, often improvising scenes with his regular cast members. The film was likely shot in sequence, as was common with Keystone productions, allowing for natural comedic timing to develop. The park scenes presented challenges as filming in public locations often drew curious crowds who sometimes wandered into shots unintentionally, occasionally being incorporated into the final film.

Visual Style

The cinematography by standard Keystone cameramen utilized the fixed camera positions typical of the era, with minimal camera movement. The film employed the classic wide shot followed by medium shots for comedic effect, allowing audiences to see both the setup and the physical gags clearly. The park scenes benefited from natural lighting, while interior scenes used the newly adopted electric lighting systems. The tintype close-up was a key visual moment, requiring careful framing to establish the mistaken identity premise.

Innovations

While not technically innovative, the film demonstrated Keystone's efficient production methods and Arbuckle's mastery of visual comedy. The use of tintype photography as a plot device showed an understanding of contemporary technology and its integration into storytelling. The film's editing, though basic by modern standards, effectively timed the reveals and comedic moments for maximum impact. The outdoor filming in natural light represented the ongoing transition from studio-bound productions to more location-based filming.

Music

As a silent film, it would have been accompanied by live musical performance in theaters. Typical Keystone scores included popular songs of the era, classical pieces, and improvisational piano accompaniment. The mood would shift between light comedic themes during the slapstick moments and more dramatic music during the jealousy scenes. Theaters often used cue sheets provided by the studio to guide musicians, though individual pianists frequently added their own interpretations.

Did You Know?

- This was one of over 40 films Arbuckle directed and starred in during 1915 alone, showcasing his incredible productivity during the Keystone era.

- The tintype (ferrotype) photography method used in the plot was still common in 1915, though rapidly being replaced by more modern photographic processes.

- Joe Bordeaux, who plays the jealous husband, was a regular Arbuckle collaborator appearing in dozens of his films.

- The film's premise of mistaken identity through photography was a recurring theme in silent comedies, reflecting society's growing fascination with visual media.

- Keystone Studios was known for shooting films quickly, often completing a short in just 1-3 days.

- The 'Dutch courage' whiskey reference was common in films of this era, though actual drinking on screen was often simulated.

- Glen Cavender, another Arbuckle regular, would later appear in Buster Keaton's films after Arbuckle helped launch Keaton's career.

- The film was released during the peak of Keystone's influence on American comedy, before Chaplin's departure changed the studio's dynamics.

- Arbuckle's character's rebellion against domestic authority reflected changing gender roles in early 20th century America.

- The park setting was a staple of Keystone comedies, allowing for public filming and unexpected encounters with real pedestrians.

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews in trade publications like The Moving Picture World praised Arbuckle's comedic timing and the film's clever premise. Critics noted the effective use of the tintype as a plot device and appreciated the film's pacing. Modern film historians recognize it as a solid example of Keystone's output during its golden age, though it's not considered among Arbuckle's most innovative works. The film is valued today for its representation of early American comedy style and Arbuckle's directorial approach.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by contemporary audiences who were familiar with Arbuckle's work and the Keystone style of comedy. Theater owners reported good attendance for Arbuckle's shorts, which were reliable crowd-pleasers. The mistaken identity premise and physical comedy appealed to the broad immigrant audiences that made up much of early cinema's demographic. Modern audiences viewing the film at silent film festivals and in archival screenings appreciate its historical value and straightforward comedic approach.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Mack Sennett's Keystone style

- French farce traditions

- Vaudeville comedy routines

- Chaplin's early shorts

- Max Linder's comedies

This Film Influenced

- Later Arbuckle-Keaton collaborations

- Hal Roach comedy shorts

- Three Stooges mistaken identity shorts

- Modern romantic comedies with similar premises