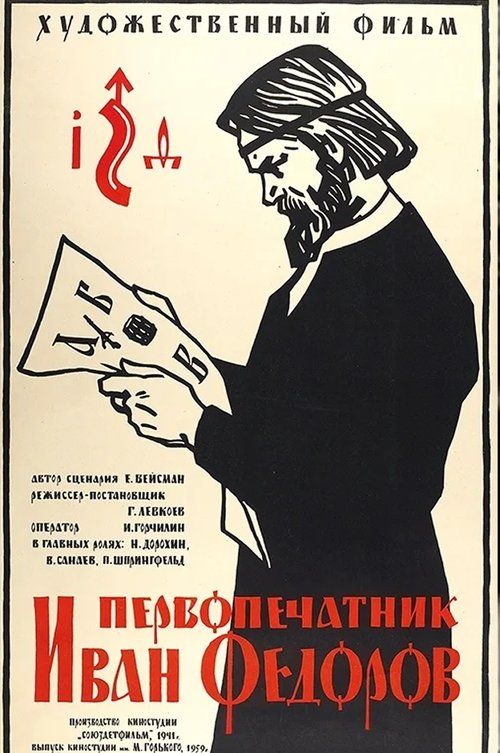

First Printer Ivan Fedorov

"From darkness to light, one man brought knowledge to Russia"

Plot

The film chronicles the life of Ivan Fedorov, the pioneering Russian printer who established the first printing press in Moscow during the reign of Ivan the Terrible. Fedorov, working alongside his partner Pyotr Mstislavets, faces tremendous opposition from religious scribes who view printed books as witchcraft and a threat to their livelihood. Despite accusations of heresy and persecution from church authorities, Fedorov perseveres in his mission to bring knowledge to the Russian people through mass-produced books. The story follows his journey from establishing the Moscow Print Yard to his eventual exile in Lithuania, where he continues his printing work. The film portrays Fedorov as a progressive thinker fighting against medieval superstition and religious dogma in his quest to enlighten Russian society.

About the Production

The film was completed just before Nazi Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, making it one of the last pre-war historical epics. Production faced challenges due to the impending war, with resources being diverted to military needs. The filmmakers had to recreate 16th-century Moscow using limited sets and resources available during wartime preparations. Historical accuracy was balanced with Soviet ideological requirements, emphasizing the progressive nature of Fedorov's work while portraying religious opponents as backward and reactionary.

Historical Background

The film was produced during a critical period in Soviet history, just months before Operation Barbarossa and the Great Patriotic War. 1941 saw the Soviet Union under Stalin's rule, with cinema serving as both entertainment and propaganda. The choice to make a film about a 16th-century printer reflected Soviet emphasis on education, literacy, and technological progress as pillars of communist society. The film's anti-clerical stance aligned with the state's official atheist position. The timing of the release, just before the German invasion, meant the film had limited theatrical exposure as Soviet cinema immediately pivoted to war-themed productions. The film's themes of enlightenment versus superstition resonated with Soviet narratives about overcoming backwardness through scientific socialism.

Why This Film Matters

The film represents an important example of Soviet historical cinema that sought to reclaim Russian cultural figures for the Soviet narrative. By portraying Ivan Fedorov as a progressive hero fighting against religious reaction, the film contributed to the Soviet project of reinterpreting Russian history through a Marxist lens. The film helped educate Soviet citizens about the history of printing and literacy in Russia, supporting the state's literacy campaigns. It also demonstrated how Soviet cinema could create elaborate historical epics despite technical and resource limitations. The film's emphasis on the transformative power of knowledge and technology reflected core Soviet values and the belief in progress through science and education.

Making Of

The production faced significant challenges due to the geopolitical tensions of 1940-1941. Director Grigori Levkoyev worked closely with historical consultants to ensure period accuracy, though Soviet censorship required certain historical interpretations to align with communist ideology. The casting of Nikolai Dorokhin as Ivan Fedorov was considered a major coup, as he was one of the Soviet Union's most respected dramatic actors. The film's elaborate costumes and props were created by artisans who would soon be redirected to work on military uniforms and equipment. The final editing was completed under great pressure as the German invasion loomed, with some historians suggesting the film's anti-clerical themes were emphasized to support Soviet propaganda needs. Despite these challenges, the production team managed to create a visually impressive historical epic that captured the spirit of 16th-century Russian intellectual life.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Boris Monastyrev employed chiaroscuro lighting techniques to emphasize the conflict between enlightenment and darkness, both literally and metaphorically. The film used deep focus photography to capture the intricate details of the 16th-century printing press and workshop scenes. Camera movements were generally restrained, reflecting the serious, didactic nature of the historical subject matter. The visual style incorporated elements of Russian Orthodox iconography in its composition, creating a visual link between the religious context and the secular innovation Fedorov represented. The battle between tradition and progress was visualized through contrasting shots of dimly lit scriptoriums versus the brighter, more organized printing workshop.

Innovations

The film featured innovative techniques for recreating 16th-century printing processes, with special effects showing the transformation of blank pages into printed text. The production team constructed a working replica of Fedorov's printing press based on historical research, allowing for authentic filming of the printing process. The film's makeup and prosthetics department created convincing aging effects for the main character, showing Fedorov's progression from young innovator to elderly master craftsman. The battle sequences and crowd scenes used innovative matte painting techniques to create the illusion of 16th-century Moscow on a limited budget. The film also pioneered techniques for showing the printing process in cinematic form, using macro photography and time-lapse effects to demonstrate the technical aspects of early book production.

Music

The musical score was composed by Vladimir Yurovsky, who incorporated elements of 16th-century Russian liturgical music adapted for symphony orchestra. The soundtrack featured traditional Russian instruments alongside Western classical arrangements, reflecting the cultural crossroads that Fedorov represented. Choral passages were used to emphasize the religious conflicts central to the story. The main theme, representing Fedorov's struggle and triumph, became one of the most recognizable pieces of Soviet film music from the early 1940s. Sound design emphasized the mechanical sounds of the printing press as a symbol of progress and modernity, contrasting with the more organic sounds of traditional manuscript creation.

Famous Quotes

A printed book is not witchcraft, it is knowledge made available to all who can read.

They call me heretic for wanting to share God's word with every Russian, not just the privileged few.

Every page I print is a victory against darkness and ignorance.

The ink may stain my hands, but it cleanses the minds of those who read.

In this age of iron and fire, we must forge knowledge as we forge weapons.

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic scene where Ivan Fedorov demonstrates the printing press to skeptical church officials, showing how multiple identical pages can be produced quickly

- The emotional confrontation where Fedorov is accused of heresy and must defend his work before a church tribunal

- The montage sequence showing the first complete book being printed, with close-ups of each step in the process

- The farewell scene where Fedorov leaves Moscow, carrying his printing equipment into exile

- The final scene showing children reading printed books for the first time, symbolizing the future Fedorov created

Did You Know?

- This was one of the last major historical films completed before WWII disrupted Soviet cinema production

- The film's release coincided with the 400th anniversary of Ivan Fedorov's death (1583-1983, though the film was made earlier)

- Director Grigori Levkoyev specialized in historical films and biographies of Russian cultural figures

- The actual printing press equipment used in the film was reconstructed based on historical drawings and descriptions

- Nikolai Dorokhin, who played Ivan Fedorov, was a prominent stage actor at the Moscow Art Theatre

- The film was temporarily withdrawn from circulation after the Nazi invasion as Soviet cinema shifted to war propaganda

- Historical documents show Ivan Fedorov was indeed accused of heresy, though the film dramatizes these events

- The film's portrayal of religious opposition reflected Soviet state policy toward organized religion

- Some scenes were filmed at the former Moscow Print Yard, the actual location where Fedorov worked

- The film's score incorporated elements of 16th-century Russian church music, adapted for the orchestra

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film for its historical significance and artistic merits, particularly noting Nikolai Dorokhin's powerful performance as Ivan Fedorov. Pravda and other official publications highlighted the film's educational value and its portrayal of the struggle between enlightenment and reaction. Western critics had limited access to the film due to wartime restrictions, but those who saw it noted its impressive production values for the period. Modern film historians view the work as an important example of Soviet historical cinema, though they note the inevitable ideological distortions required by the Stalinist system. The film is recognized for its contribution to preserving the memory of Ivan Fedorov's achievements, even while acknowledging its propagandistic elements.

What Audiences Thought

The film received positive responses from Soviet audiences, particularly among educated viewers who appreciated its historical subject matter. School teachers used the film as an educational tool to teach students about the history of Russian printing and culture. Audience letters to newspapers praised the film's patriotic elements and its celebration of Russian cultural achievement. However, the film's theatrical run was cut short by the outbreak of war, limiting its overall audience impact. In the post-war years, the film was occasionally shown on television and in special screenings, maintaining its status as a respected work of Soviet historical cinema. Modern Russian audiences viewing the film often appreciate its historical value while recognizing its period-specific ideological framework.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize, Second Class (1941)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Alexander Nevsky (1938) - for its historical epic style

- Lenin in 1918 (1939) - for its portrayal of historical leadership

- Ivan the Terrible (1944) - though released later, both films dealt with the same historical period

- Russian historical literature about Fedorov

- Traditional Russian Orthodox iconography

This Film Influenced

- Andrey Rublyov (1966) - another film about a Russian cultural innovator facing religious opposition

- Pushkin (1937) - similar biographical approach to Russian cultural figures

- The Great Citizen (1938) - shared themes of individual struggle against reactionary forces

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the Gosfilmofond of Russia, the state film archive. A restored version was released in the 1970s as part of a Soviet classic film restoration project. The original negative survived WWII and has been digitally remastered for modern viewing. Some minor damage exists in certain reels, but the film is considered complete and viewable. The restored version includes improved sound quality and color correction of the black and white photography.