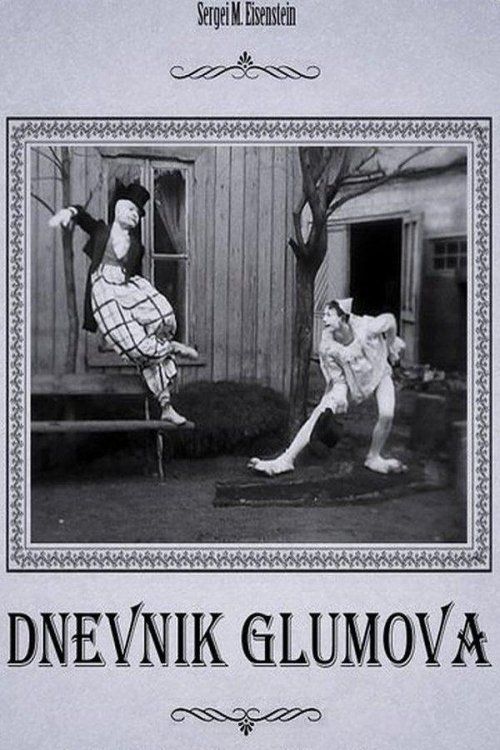

Glumov's Diary

Plot

Glumov's Diary serves as a cinematic insert within Eisenstein's stage production of Ostrovsky's 'The Wise Man.' The film follows the anti-hero Glumov, a cunning character who desperately attempts to escape exposure after his schemes are discovered. Through a series of acrobatic sequences, daring stunts, and farcical clowning, Glumov navigates increasingly absurd situations while trying to maintain his deception. The narrative showcases Eisenstein's early experimentation with montage and visual comedy, blending theatrical performance with cinematic techniques. Members of Eisenstein's Proletkult theatre troupe appear throughout, creating a meta-theatrical experience that blurs the lines between stage and screen.

About the Production

Created specifically as a filmic insert for Eisenstein's stage production of 'The Wise Man' at the Proletkult Theatre. The film was shot in extremely primitive conditions with limited equipment and resources. Eisenstein used this project to experiment with his developing theories of montage and intellectual cinema. The production involved members of his experimental theatre troupe who performed both on stage and in the film segments.

Historical Background

Glumov's Diary was created in 1923, during the early years of the Soviet Union and a period of tremendous artistic experimentation. The Russian Revolution had occurred just six years earlier, and the new Bolshevik government was encouraging innovative art that served revolutionary purposes. This was the height of the avant-garde movement in Russia, with artists across all mediums breaking with traditional forms. Cinema was still in its infancy, particularly in the newly formed Soviet Union, which was struggling to rebuild its film industry after years of war and revolution. The Proletkult (Proletarian Culture) movement, under which Eisenstein worked, aimed to create a new culture for the working class, free from bourgeois influences. This context of radical artistic and political experimentation directly influenced Eisenstein's innovative approach to filmmaking.

Why This Film Matters

Glumov's Diary holds immense cultural significance as the birthplace of Sergei Eisenstein's cinematic genius and a foundational text of Soviet montage theory. Though brief, it represents the moment when one of cinema's greatest theorists first translated his ideas to film. The film's experimental approach to integrating cinema with theatre anticipated later multimedia and interdisciplinary art forms. Its preservation and study provide crucial insight into the development of film language and the birth of modern cinema. The film exemplifies the revolutionary spirit of early Soviet art, which sought to completely reinvent artistic forms for a new social order. Its influence extends far beyond its brief runtime, affecting generations of filmmakers who studied Eisenstein's theories and techniques.

Making Of

The production of Glumov's Diary took place under extremely challenging conditions in post-revolutionary Russia. Eisenstein, working with minimal resources and primitive equipment, had to improvise many technical solutions. The film was shot in a makeshift studio space at the Proletkult Theatre, with lighting provided by whatever was available. The cast consisted primarily of theatre actors from Eisenstein's troupe, many of whom had never before appeared in a film. Eisenstein used this opportunity to test his developing theories about the psychological impact of montage and the relationship between theatrical and cinematic performance. The integration of film into a live theatrical production was revolutionary for its time, requiring careful timing and coordination between stage performers and projectionists.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Glumov's Diary reflects both the technical limitations of early Soviet cinema and Eisenstein's innovative vision. The camera work includes dynamic angles and movements that were unusual for the period, demonstrating Eisenstein's early understanding of visual storytelling. The film employs what would become signature Eisenstein techniques including close-ups for emotional emphasis and wide shots to establish context. Despite primitive equipment, the cinematography shows remarkable compositional awareness and experimental courage. The visual style bridges theatrical performance and cinematic language, using the camera to enhance rather than merely record the action.

Innovations

Glumov's Diary pioneered several technical innovations despite its minimal resources and brief duration. The film represents one of the earliest successful integrations of cinema with live theatre, a technical and artistic challenge that required precise timing and coordination. Eisenstein experimented with jump cuts and rhythmic editing techniques that would later become fundamental to his montage theory. The film's acrobatic sequences required innovative camera setups to capture the dynamic movement effectively. Perhaps most significantly, the film demonstrated how cinematic techniques could enhance theatrical performance, laying groundwork for future multimedia art forms.

Music

As a silent film, Glumov's Diary would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical presentations. The specific musical arrangements are not documented, but they would likely have reflected the avant-garde nature of the production. Modern screenings typically feature contemporary scores that attempt to capture the revolutionary spirit of the original. The absence of recorded dialogue forced Eisenstein to rely entirely on visual storytelling, a constraint that ultimately strengthened his cinematic language and contributed to the development of his montage theory.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film with no intertitles documented, specific quotes are not available, but the film's visual language speaks through its innovative montage and dynamic compositions.

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic acrobatic sequence where Glumov attempts to escape exposure through increasingly daring physical feats

- The opening montage introducing Glumov's character through quick cuts and expressive angles

- The meta-theatrical moments where the film acknowledges its own artificiality

- The sequence where multiple members of Eisenstein's troupe appear in rapid succession

- The final scene where theatrical and cinematic realities merge

Did You Know?

- This was Sergei Eisenstein's very first film, marking his transition from theatre to cinema

- The film was never intended for standalone theatrical release but was created as an innovative insert within a stage play

- Glumov's Diary is considered lost for decades before being rediscovered and restored

- The film showcases Eisenstein's early experiments with what would later become his famous montage theory

- Grigori Aleksandrov, who plays Glumov, would become one of Soviet cinema's most prominent directors

- The film was created during Eisenstein's tenure at the Proletkult Theatre, a revolutionary cultural organization

- Despite its brevity, the film contains multiple revolutionary techniques including jump cuts and expressive camera angles

- The character of Glumov was adapted from Alexander Ostrovsky's 19th-century play but modernized for Soviet audiences

- Eisenstein himself appears briefly in the film, making one of his rare acting appearances

- The film's survival is remarkable given the fragility of early Soviet film stock and the chaos of the following decades

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of Glumov's Diary was limited due to its nature as a theatrical insert rather than a standalone film. However, those within the Soviet avant-garde circle recognized its innovative qualities. Later critics and film historians have come to view it as a crucial document in cinema history, marking the beginning of Eisenstein's revolutionary contributions to film art. Modern scholars praise the film for its bold experimentation and its role in developing montage theory. The film is now studied in film schools worldwide as an example of early Soviet avant-garde cinema and the genesis of Eisenstein's cinematic language.

What Audiences Thought

Original audience reception was confined to theatre-goers at the Proletkult who experienced the film as part of the larger stage production. Reports suggest audiences were intrigued by the novel integration of film into live theatre, a technique they had likely never witnessed before. The acrobatic and comedic elements of Glumov's character were particularly well-received by working-class audiences for whom the Proletkult productions were intended. Modern audiences viewing the restored film often express fascination with its primitive charm and historical importance, though its experimental nature can be challenging for contemporary viewers accustomed to conventional narrative cinema.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Proletkult theatrical experiments

- Vsevolod Meyerhold's biomechanics

- Dziga Vertov's kino-eye theory

- Georges Méliès's trick films

- American slapstick comedy

- Russian theatrical tradition

This Film Influenced

- Strike (1925)

- Battleship Potemkin (1925)

- October: Ten Days That Shook the World (1928)

- The General Line (1929)

- Alexander Nevsky (1938)

- Ivan the Terrible (1944-1946)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was believed lost for many years but has been rediscovered and restored by film archives. It is now preserved in several major film archives including the Gosfilmofond in Russia. The restoration has allowed modern audiences to study this crucial early work of Eisenstein. The surviving print shows signs of age and wear but remains largely complete, offering invaluable insight into the origins of Soviet montage cinema.