Greed

"The picture that will be remembered forever."

Plot

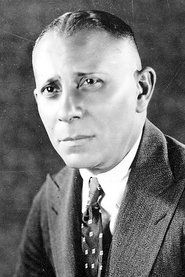

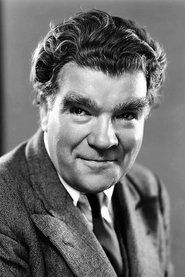

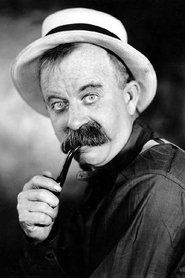

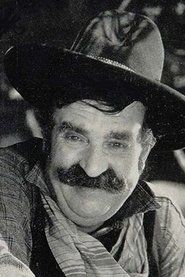

The film follows McTeague (Gibson Gowland), a simple-minded dentist who marries Trina Sieppe (Zasu Pitts) after she wins $5,000 in a lottery. Trina becomes pathologically obsessed with her newfound wealth, refusing to spend it even as they face poverty and hardship, while McTeague's friend Marcus (Jean Hersholt) grows increasingly jealous and vengeful after losing Trina's affection. As their marriage deteriorates under the weight of greed and suspicion, McTeague descends into alcoholism and violence, ultimately leading to tragedy when he murders Trina for her money. The film culminates in the brutal Death Valley sequence where McTeague, handcuffed to the dying Marcus after stealing his water, faces death alone in the scorching desert with the key to the handcuffs just out of reach.

About the Production

Erich von Stroheim shot over 42 hours of footage for his original 9-hour version, using real gold coins for the lottery money and insisting on absolute period authenticity. The Death Valley sequences were filmed in 120°F heat, causing crew members to collapse and film emulsion to melt. Von Stroheim was fired during editing after refusing to make cuts demanded by the studio, who then brought in other editors to reduce the film to 140 minutes. The production became legendary in Hollywood as 'von Stroheim's Folly' due to its extravagance and the director's uncompromising vision.

Historical Background

Greed was produced during a pivotal moment in Hollywood history when the studio system was consolidating power and imposing greater control over directors. The early 1920s saw the transition from independent production to the vertically integrated studio model that would dominate Hollywood for decades. Von Stroheim's struggle with Goldwyn Pictures exemplified the growing tension between artistic vision and commercial interests that would define Hollywood's golden age. The film's release coincided with the post-WWI economic boom and cultural fascination with wealth and materialism, making its critique of greed particularly relevant. Its stark realism and psychological complexity contrasted sharply with the more escapist entertainment popular at the time. The film was produced just before the implementation of the Hays Code in 1934, which would have heavily censored its dark themes and violent content. 'Greed' thus represents one of the last examples of unbridled artistic freedom in Hollywood before censorship became institutionalized.

Why This Film Matters

Greed revolutionized cinematic language through its unprecedented realism and psychological depth, establishing film as a medium capable of complex artistic expression. Von Stroheim's naturalistic approach to performance and his use of authentic locations influenced generations of filmmakers, from the Italian neorealists to modern directors like Paul Thomas Anderson. The film's unflinching examination of how money corrupts human relationships remains strikingly relevant in our contemporary consumer culture. Its influence can be seen in countless films dealing with the destructive nature of wealth, from 'The Treasure of the Sierra Madre' to 'There Will Be Blood.' The truncated version that survived became a symbol of artistic integrity versus commercial compromise, inspiring filmmakers to fight for their vision against studio interference. 'Greed' helped establish cinema as a serious art form worthy of academic study and critical analysis, paving the way for more sophisticated narratives and psychological complexity in film. Its reputation as a 'lost masterpiece' has made it a legendary touchstone in film history, representing both the possibilities and limitations of cinematic art.

Making Of

The production of 'Greed' became legendary in Hollywood as an example of artistic excess and directorial obsession. Von Stroheim, known as 'The Man You Love to Hate,' was given unprecedented freedom by Goldwyn Pictures, which he exploited to create his magnum opus. He insisted on absolute realism, from authentic 19th-century dental instruments to real gold coins that had to be guarded constantly. The Death Valley sequences proved particularly grueling, with the crew filming in extreme heat that caused equipment to malfunction and personnel to collapse. Von Stroheim's perfectionism extended to demanding that Zasu Pitts actually learn dental procedures and that Gibson Gowland grow an authentic beard. The director's refusal to compromise led to his dismissal during editing, with the studio taking control and cutting the film down to a fraction of its original length. This battle between artistic vision and commercial constraints became a defining moment in Hollywood history, symbolizing the tension between creative freedom and studio control.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Ben Reynolds and William H. Daniels was revolutionary for its time, featuring extensive location shooting and natural lighting techniques that were unprecedented for a major studio production. Von Stroheim demanded absolute realism, leading to the use of actual San Francisco locations and the harsh, unforgiving landscapes of Death Valley. The film employed sophisticated deep focus photography and complex tracking shots that pushed the boundaries of what was technically possible in 1924. The visual style emphasized gritty realism over the glamorous artifice typical of Hollywood productions, with careful attention to period detail in every frame. The Death Valley sequences, shot in extreme heat, created a stark, desolate visual landscape that perfectly mirrored the characters' emotional and moral desolation. The use of shadows and contrast in interior scenes created a psychological depth that would later influence film noir aesthetics. The camera work often maintained a detached, observational quality that reinforced the film's naturalistic approach.

Innovations

Greed pioneered numerous technical innovations that would become standard in filmmaking. The production's extensive location shooting was unprecedented for a major studio film of its era, establishing the practice of on-location filming for authenticity. Von Stroheim's use of deep focus photography and complex camera movements pushed the boundaries of what was technically possible in 1924. The film's editing techniques, particularly in the truncated version, demonstrated sophisticated narrative compression and visual storytelling. The production design achieved remarkable period authenticity through meticulous research and attention to detail, from authentic dental instruments to historically accurate costumes. The Death Valley sequences required developing new techniques for filming in extreme conditions, including special camera housings and film stock modifications to withstand the intense heat. The film also pioneered the use of psychological realism in performance, with von Stroheim demanding naturalistic acting styles that contrasted with the exaggerated performances common in silent cinema.

Music

As a silent film, 'Greed' was originally accompanied by live musical performances that varied by theater and region. The typical score consisted of classical pieces, popular songs of the era, and specially composed cues selected by theater musicians to match the film's dramatic moments. Von Stroheim reportedly provided detailed musical suggestions for the original screenings, though these were not always followed. Modern restorations have featured newly composed scores by artists such as Carl Davis, Robert Israel, and the Alloy Orchestra. These contemporary scores attempt to capture the film's psychological complexity while respecting its silent era origins, often using leitmotifs for different characters and themes. The music emphasizes the tragic elements of the story while avoiding melodrama, reflecting von Stroheim's naturalistic approach to the material. Some modern screenings have experimented with alternative musical approaches, including jazz and experimental compositions.

Famous Quotes

I'll kill you, McTeague! I'll kill you! - Marcus Schouler

The money is mine! I won it! It's mine! - Trina Sieppe

You're a dentist, McTeague. You should know better than to drink. - Marcus Schouler

I'm not afraid of you. I'm not afraid of anything. - McTeague

The desert doesn't care about money. It only cares about survival. - Implied theme

You can't have my money! It's all I have! - Trina Sieppe

I trusted you, Marcus. I trusted you. - McTeague

Memorable Scenes

- The lottery ticket discovery scene where Trina's life changes forever with the announcement of her $5,000 win

- The wedding scene showing the beginning of McTeague and Trina's doomed marriage, filled with hope and innocence

- The dental surgery sequence demonstrating McTeague's professional skill and underlying brutality

- The money-hoarding scene where Trina obsessively counts and polishes her gold coins in secret

- The brutal fight between McTeague and Trina over the hidden money, leading to her murder

- The Death Valley pursuit sequence with McTeague dragging the dying Marcus across the desert

- The final haunting image of McTeague, handcuffed to a corpse, facing death alone in the scorching desert

Did You Know?

- The original 42-reel version would have been one of the longest films ever made, requiring multiple screenings over several days.

- Von Stroheim insisted on building full-scale reproductions of San Francisco streets rather than using studio backdrops.

- The production used 20,000 real gold coins for the lottery money, which required constant security guards.

- During the Death Valley shoot, temperatures reached 120°F, causing the cinematographer's camera to literally melt.

- Many cast and crew members suffered heat stroke and dehydration during the desert sequences.

- Von Stroheim demanded that actors wear period-appropriate underwear that would never be seen on camera.

- The famous final scene was shot in reverse order, starting with McTeague's collapse and working backward.

- Approximately 8 hours of footage was destroyed, though some was salvaged for von Stroheim's later films.

- The film's failure contributed to the merger that created Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM).

- Frank Norris's novel 'McTeague' was considered unfilmable due to its dark themes and complex characters.

What Critics Said

Upon its release, 'Greed' received predominantly negative reviews from contemporary critics who found it excessively long, depressing, and lacking entertainment value. The New York Times criticized its 'excessive length and morbid preoccupation with sordid details,' while Variety dismissed it as 'a dreary and depressing picture.' However, some European critics, particularly in France and Germany, recognized its artistic merit and praised its innovative techniques. Over the decades, critical opinion has shifted dramatically, with modern critics hailing it as a masterpiece of silent cinema. The film is now widely regarded as one of the greatest achievements in cinematic history, with particular praise for its visual storytelling, psychological depth, and uncompromising vision. Critics celebrate von Stroheim's meticulous attention to detail, his use of location shooting, and his ability to create complex character studies through visual means. The loss of the original cut is considered one of cinema's greatest tragedies, with many critics speculating about what might have been Hollywood's greatest film.

What Audiences Thought

Contemporary audiences largely rejected 'Greed' due to its length, dark themes, and lack of conventional entertainment value. Many viewers found the film's pessimistic worldview and unrelenting grimness difficult to stomach, particularly during the prosperous Roaring Twenties. The film was a commercial disaster, playing to half-empty theaters and contributing to Goldwyn Pictures' financial troubles. Audience members reportedly walked out during screenings, unable to endure the film's bleakness and slow pacing. However, as the film's reputation grew over the decades, it developed a cult following among film enthusiasts and students of cinema. Modern audiences, particularly those interested in film history and artistic cinema, have come to appreciate its groundbreaking techniques and powerful themes. The reconstructed 4-hour version has found appreciation at film festivals and special screenings, though its unrelenting darkness can still be challenging for viewers accustomed to more conventional narratives.

Awards & Recognition

- 1991: Selected for preservation in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress

- 1998: Ranked #7 on AFI's 100 Greatest American Movies

- 2007: Ranked #9 on AFI's 10th Anniversary 100 Greatest American Movies

- 2012: Ranked #4 in Sight & Sound's critics' poll of greatest films

- 1958: Named one of the 12 greatest films ever made at the Brussels World's Fair

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Frank Norris's novel 'McTeague: A Story of San Francisco' (1899)

- Naturalist literature of the late 19th century

- German Expressionist cinema

- The works of Émile Zola

- Victorian morality tales

- Social Darwinism

- Freudian psychology

- The literary movement of Naturalism

This Film Influenced

- The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948)

- Ace in the Hole (1951)

- Shane (1953)

- The Killing (1956)

- Psycho (1960)

- The Graduate (1967)

- Chinatown (1974)

- Raging Bull (1980)

- There Will Be Blood (2007)

- The Master (2012)

- The Revenant (2015)

- The Irishman (2019)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The original 9-hour version of 'Greed' is considered lost, though approximately 8 hours of footage was destroyed by the studio. In 1999, Turner Classic Movies produced a four-hour reconstructed version using over 650 production still photographs and the original continuity script. This version, titled 'Greed: The Lost Version,' provides the most complete representation of von Stroheim's vision possible. The surviving 140-minute theatrical version has been preserved by the Museum of Modern Art and designated for preservation by the Library of Congress in the National Film Registry. Various restoration efforts have improved the film's visual quality over the years, including a 4K restoration by the Criterion Collection. Despite the tragic loss of the original cut, enough material survives to understand the film's original scope and artistic intentions, making it one of cinema's most famous 'lost' masterpieces.