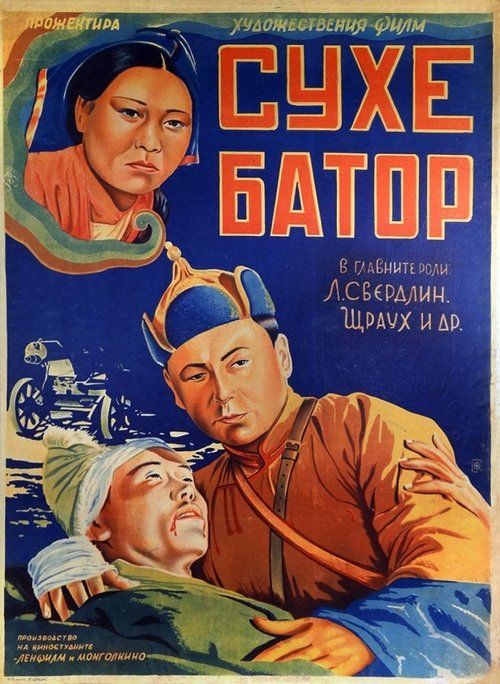

His Name Is Sukhe-Bator

"The story of Mongolia's liberation and the hero who led his people to freedom"

Plot

The film chronicles the life and revolutionary struggles of Damdin Sukhe-Bator, the founder of the Mongolian People's Revolutionary Party and leader of Mongolia's 1921 revolution. Set against the backdrop of Mongolia's struggle against Chinese occupation and foreign influence, the narrative follows Sukhe-Bator from his early days as a soldier to his emergence as a revolutionary leader. The film depicts his formation of the revolutionary movement, his alliance with Soviet Russia, and the successful uprising that established the Mongolian People's Republic. Key events include his secret meetings with revolutionaries, the establishment of the People's Army, and the decisive battles that liberated Mongolia from foreign control. The story culminates with Sukhe-Bator's triumph and the birth of an independent socialist Mongolia, though it hints at his tragic early death from illness shortly after the revolution's success.

About the Production

This was a joint Soviet-Mongolian production, one of the first such collaborations between the two countries. The filming took place during World War II, creating significant logistical challenges. Parts of the film were shot on location in Mongolia, which was unusual for the time due to wartime conditions. The production involved extensive research into Mongolian history and culture, with Mongolian historical consultants ensuring authenticity. The battle sequences were filmed using real Mongolian soldiers as extras, adding to the authenticity of the revolutionary scenes.

Historical Background

Made in 1942 during the darkest days of World War II, 'His Name Is Sukhe-Bator' served multiple purposes for Soviet wartime propaganda. The film emphasized themes of liberation from foreign occupation, paralleling Mongolia's struggle against Chinese control with the Soviet Union's fight against Nazi Germany. It also highlighted the historical friendship and revolutionary solidarity between the Soviet and Mongolian peoples at a time when Mongolia was serving as an important ally against Japan. The film reinforced the Soviet narrative of supporting national liberation movements while promoting socialist revolution. Additionally, it served to legitimize the Soviet presence in Mongolia and the communist government there. The timing was crucial - with the Soviet Union facing existential threat, the film reminded audiences of past victories against foreign oppressors and the righteousness of the revolutionary cause.

Why This Film Matters

This film holds a unique place in cinema history as one of the earliest major co-productions between the Soviet Union and Mongolia, establishing a template for future collaborations between socialist countries. It played a crucial role in shaping the historical memory of Sukhe-Bator, transforming him from a revolutionary leader into a socialist hero and founding father figure. The film's visual representation of Mongolian history influenced how generations of Soviets and Mongolians understood their shared revolutionary past. It also demonstrated how Soviet cinema could adapt its historical epic formula to non-Russian subjects while maintaining ideological consistency. The film's success paved the way for more Soviet productions about allied socialist countries and their revolutionary histories. Its portrayal of international revolutionary solidarity became a model for similar films throughout the Eastern Bloc.

Making Of

The production of 'His Name Is Sukhe-Bator' was a monumental undertaking during wartime. Director Aleksandr Zarkhi and his crew faced numerous challenges, including resource shortages due to the war and the need to coordinate between Soviet and Mongolian authorities. The casting process was particularly careful, as the film needed to balance historical accuracy with Soviet ideological requirements. Lev Sverdlin underwent extensive preparation, including learning basic Mongolian and studying period photographs and documents. The battle sequences were choreographed with military advisors to ensure historical accuracy. The film's score was composed by Vladimir Yurovsky, who incorporated traditional Mongolian musical elements into the orchestral score. The production also faced political challenges, as it needed to satisfy both Soviet and Mongolian authorities regarding historical interpretation and ideological messaging.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Yuri Yekelchik combined Soviet realist traditions with epic scale. The film utilized sweeping landscape shots of the Mongolian steppe to emphasize the vastness of the country and the scale of the revolutionary struggle. Battle sequences employed innovative camera techniques for the time, including dynamic tracking shots that followed cavalry charges. The contrast between the open spaces of Mongolia and the intimate close-ups of revolutionary meetings created visual variety and emphasized both the collective nature of the revolution and individual heroism. The film used natural lighting extensively, particularly in outdoor scenes, giving it an authentic feel. The cinematography also incorporated traditional Mongolian visual motifs and symbols, carefully integrated with Soviet visual language to create a unique aesthetic that honored both cultures.

Innovations

Despite being produced during wartime with limited resources, the film achieved several technical milestones. The battle sequences featured some of the most elaborate cavalry charges filmed in Soviet cinema up to that point, involving hundreds of horsemen. The production pioneered techniques for filming in extreme weather conditions on the Mongolian steppe. The film also featured innovative use of miniature models for certain wide shots of Ulan Bator, combined with matte paintings to create convincing historical urban environments. The sound recording team developed new methods for capturing clear dialogue in outdoor, windy conditions. The makeup and costume departments created historically accurate representations of early 20th-century Mongolian military and civilian dress, based on extensive archival research. The film's editing, particularly in the battle scenes, employed rapid cutting techniques that were advanced for the time and influenced later Soviet war films.

Music

The musical score by Vladimir Yurovsky masterfully blended Western classical orchestration with traditional Mongolian musical elements. Yurovsky incorporated authentic Mongolian instruments and folk melodies, creating a sound that was both familiar to Soviet audiences and respectful of Mongolian musical traditions. The score featured powerful, martial themes for the battle sequences and more intimate, emotional melodies for scenes of personal sacrifice and revolutionary conviction. The film's main theme, representing Sukhe-Bator himself, became recognizable to Soviet audiences and was later used in documentaries about Mongolia. The soundtrack also included actual Mongolian folk songs performed by traditional singers, adding cultural authenticity. The music was recorded with the full resources of the Soviet state recording system, despite wartime limitations, resulting in a rich, full sound that enhanced the film's epic scope.

Famous Quotes

A people who have known slavery will never accept chains again!

Our revolution is not just for Mongolia, but for all oppressed peoples!

When the people rise, no empire can stand against them!

Freedom is not given, it must be taken with the sword of justice!

The friendship between Mongolia and Soviet Russia is unbreakable, forged in the fires of revolution!

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic cavalry charge across the steppe during the final battle for Ulan Bator, with hundreds of horsemen silhouetted against the setting sun

- Sukhe-Bator's impassioned speech to the revolutionary council, where he declares Mongolia's independence

- The secret meeting in the yurt where revolutionaries plot their uprising, illuminated by candlelight

- The victory celebration in liberated Ulan Bator, with traditional Mongolian music and dancing

- The emotional farewell scene between Sukhe-Bator and his family as he goes to lead the revolution

Did You Know?

- Lev Sverdlin, who played Sukhe-Bator, spent months studying Mongolian culture and language to prepare for the role

- The film was made during the height of World War II, making it one of the few major Soviet historical productions during this period

- Nikolai Cherkasov, who played a supporting role, was one of Stalin's favorite actors and had recently starred in 'Alexander Nevsky'

- The real Sukhe-Bator's widow and other family members served as consultants on the film

- This was one of the first films to depict Mongolian history on such a grand scale

- The film's premiere was attended by Mongolian and Soviet dignitaries, including Choibalsan, the leader of Mongolia at the time

- Battle scenes used over 1,000 extras, many of whom were actual Mongolian soldiers

- The film's title in Russian is 'Ego zovut Sukhe-Bator'

- Director Aleksandr Zarkhi had to evacuate from Moscow during part of the production due to German advances

- The film was immediately banned in China and other countries friendly to the Nationalist Chinese government

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film as a masterful blend of historical accuracy and artistic achievement. Pravda called it 'a worthy tribute to the friendship between Soviet and Mongolian peoples' and highlighted Sverdlin's performance as 'deeply moving and historically faithful.' The film was particularly noted for its epic battle sequences and authentic recreation of early 20th-century Mongolia. Western critics had limited access to the film during the war, but those who saw it at rare screenings noted its technical excellence despite wartime production constraints. Modern film historians recognize it as an important example of Soviet wartime cinema and a significant work in the genre of revolutionary biopics. Some contemporary critics note the film's propagandistic elements but acknowledge its artistic merits and historical importance as a cultural document of Soviet-Mongolian relations.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enthusiastically received by Soviet audiences, particularly as it offered a story of revolutionary victory during the difficult war years. Soviet viewers appreciated the spectacle of the battle scenes and the heroic portrayal of Sukhe-Bator. In Mongolia, the film was especially significant, as it was one of the first major cinematic treatments of their national history and revolutionary struggle. Mongolian audiences reportedly wept during scenes depicting their liberation from foreign control. The film became a regular feature in both Soviet and Mongolian cinemas for years after its release and was frequently shown at schools and party meetings as educational material. Even decades later, older audiences in both countries recalled the film with nostalgia as an important part of their cultural education and understanding of shared revolutionary history.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize, Second Class (1943)

- Order of the Red Banner of Labor awarded to director Aleksandr Zarkhi

- State Prize of the Mongolian People's Republic (1943)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Sergei Eisenstein's historical epics like 'Alexander Nevsky'

- Soviet socialist realist tradition

- Traditional Mongolian oral epic storytelling

- Earlier Soviet biopics of revolutionary leaders

- Classical Hollywood historical films (in terms of scale and spectacle)

This Film Influenced

- Later Soviet-Mongolian co-productions

- Other socialist biopics of national revolutionary leaders

- Post-war Soviet historical epics

- Mongolian films about their revolutionary history

- Eastern Bloc films about international revolutionary solidarity

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the Gosfilmofond archive in Russia and the Mongolian National Film Archive. A restored version was completed in 1975 for the 30th anniversary of the victory over fascism. The film underwent digital restoration in 2015 as part of a joint Russian-Mongolian cultural heritage project. The original camera negative survived the war years and is considered to be in good condition, though some sequences show signs of deterioration common to films of this era. Multiple language versions exist, including the original Russian, Mongolian, and dubbed versions for international distribution.