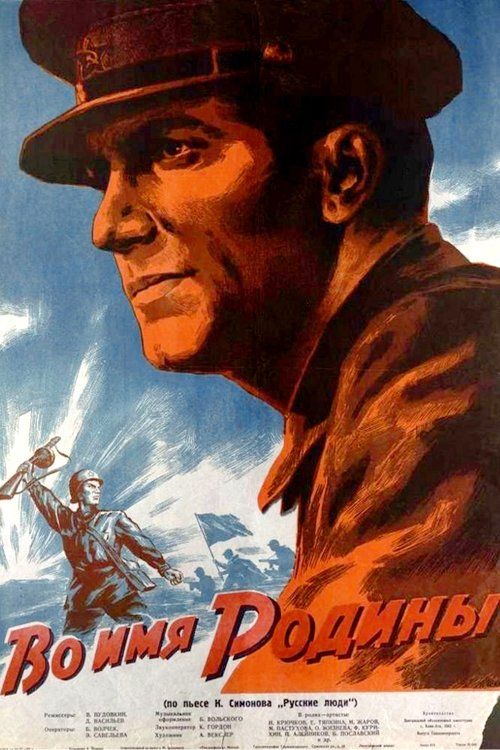

In the Name of the Motherland

"For the Motherland! For Stalin!"

Plot

Set during the brutal winter of 1941-42, the film follows a Soviet infantry battalion that becomes encircled by German forces in a desperate defensive position. Commander Major Lavrov, played by Nikolay Kryuchkov, must maintain his unit's morale and fighting spirit despite overwhelming odds, dwindling supplies, and constant enemy attacks. The narrative interweaves the personal stories of soldiers from diverse backgrounds across the Soviet Union, united in their determination to defend their motherland. As the siege intensifies, the battalion executes a daring counterattack that breaks through the German encirclement, demonstrating Soviet resilience and military prowess. The film culminates in a heroic sacrifice that allows the main force to escape, embodying the ultimate patriotic devotion to the Soviet cause.

About the Production

Filmed during active wartime conditions with many actual soldiers as extras. The production was evacuated from Moscow to Sverdlovsk during the German advance. Director Pudovkin incorporated real battle footage and used actual military equipment. The film was completed in record time under government pressure to produce patriotic content.

Historical Background

The film was produced during the pivotal turning point of World War II on the Eastern Front, following the Soviet victory at Stalingrad but while the outcome remained uncertain. In 1943, the Soviet film industry was operating under strict state control, with all productions serving the war effort through propaganda. The encirclement battles depicted were based on real events from the disastrous Soviet summer of 1941, when hundreds of thousands of soldiers were trapped by German blitzkrieg tactics. This film represented a shift in Soviet war cinema from earlier optimistic portrayals to more realistic depictions of hardship and sacrifice, while still maintaining the required heroic narrative. The production occurred during the largest civilian and military mobilization in history, with resources severely rationed and the entire Soviet society oriented toward total war.

Why This Film Matters

This film became a template for Soviet war cinema, establishing conventions that would persist for decades. It codified the portrayal of the ideal Soviet soldier - brave, selfless, and devoted to the motherland. The film's success demonstrated the effectiveness of cinema as a propaganda tool during wartime, influencing subsequent Soviet productions. Its distribution across all Soviet republics helped forge a unified national identity during the crisis. The film's depiction of multi-ethnic unity among Soviet soldiers became a recurring theme in later war films. Internationally, it served as one of the earliest cinematic representations of the Eastern Front experience for Western audiences. The film's technical achievements in battle sequence choreography influenced military filmmakers worldwide.

Making Of

The production faced extraordinary challenges during its creation in 1942-43. With Moscow under threat, the Mosfilm studio was partially evacuated to Sverdlovsk (modern Yekaterinburg), where filming continued in harsh winter conditions. Director Pudovkin, already a celebrated filmmaker, was under intense pressure from Stalin's regime to create effective propaganda. He worked closely with military officials to ensure the film's tactics and equipment were accurate, even incorporating real front-line footage where possible. The casting process prioritized actors who could embody the ideal Soviet soldier archetype, with many having actual military experience. The film's battle sequences were choreographed with military precision, using real soldiers as background performers to achieve maximum authenticity. Pudovkin employed his signature montage techniques to create emotionally powerful sequences that emphasized Soviet heroism and German barbarism.

Visual Style

The cinematography, led by Yuri Ekeltchik, employed stark black and white contrasts to emphasize the moral dichotomy between Soviet heroes and German invaders. Extensive use of low-angle shots during heroic moments elevated the Soviet soldiers to mythic status. The battle sequences utilized innovative camera techniques, including cameras mounted on moving vehicles and crane shots to capture the scale of combat. Pudovkin's montage theory was applied to create rhythmic editing patterns that built emotional intensity during action scenes. The winter landscape was photographed to emphasize both its beauty and its deadly nature, using deep focus to show the vastness of the Russian terrain. Night scenes were particularly notable for their dramatic use of shadow and limited lighting to create tension.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations in Soviet cinema, particularly in the filming of large-scale battle sequences. The production team developed new techniques for simulating explosions and artillery fire that were both realistic and safe for actors. The film's use of actual military equipment, including tanks and artillery pieces, was unprecedented in Soviet filmmaking. The editing techniques employed during combat scenes influenced subsequent war films globally. The sound recording team overcame significant challenges to capture clear dialogue during noisy battle sequences. The film's successful integration of documentary footage with staged scenes set a new standard for wartime cinema.

Music

The musical score was composed by Nikolai Kryukov, who incorporated traditional Russian folk melodies with classical orchestral arrangements. The soundtrack prominently featured patriotic songs that became popular outside the film, including 'In the Name of the Motherland,' which became an unofficial anthem for Soviet soldiers. The music was designed to swell during heroic moments and recede during scenes of sacrifice, creating an emotional arc that paralleled the narrative. The film's sound design was innovative for its time, using authentic battlefield recordings mixed with studio effects to create realistic combat audio. The German characters were often accompanied by dissonant, minor-key motifs to emphasize their villainy.

Famous Quotes

For the Motherland! For Stalin! Charge!

In the Russian winter, even the frost fights for us.

A soldier who fears death has already lost his life.

We may die, but Russia will live forever.

Every meter of ground we defend is a meter closer to victory.

The German sees a soldier, but we see the future of our children.

In this battalion, there are no Russians, Ukrainians, or Georgians - only Soviet soldiers defending their home.

Memorable Scenes

- The final charge scene where Major Lavrov leads his remaining soldiers in a desperate bayonet attack against overwhelming German forces, set against a dramatic sunrise over the snow-covered battlefield.

- The night scene where soldiers from different Soviet republics share their last bread and sing folk songs together, emphasizing unity in diversity.

- The emotional farewell between a young soldier and his elderly mother, filmed with Pudovkin's signature cross-cutting between the personal and the epic.

- The tactical planning sequence where the officers study maps by candlelight, their faces illuminated to show determination and resolve.

- The scene where German prisoners are treated humanely by Soviet soldiers, demonstrating moral superiority even in war.

Did You Know?

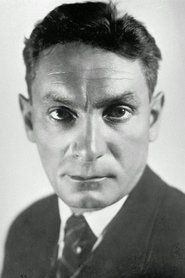

- Director Vsevolod Pudovkin was one of the pioneers of Soviet montage theory and applied these techniques to wartime propaganda

- Many of the German soldiers were played by Soviet actors who had studied German mannerisms and language

- The film was one of the first major Soviet productions to address the encirclement battles of 1941-42

- Real Soviet military advisors were on set throughout production to ensure authenticity

- The premiere was attended by Stalin and other Soviet leadership, who reportedly praised its propaganda value

- Some battle scenes were filmed using actual ammunition and explosives under military supervision

- The film's score incorporated traditional folk songs from various Soviet republics to emphasize unity

- Several cast members had recently returned from the front and brought authentic combat experiences to their roles

- The film was simultaneously dubbed into several languages of Soviet republics for wider distribution

- Production continued despite air raid warnings and occasional shelling near filming locations

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics universally praised the film as a masterpiece of wartime cinema, with Pravda calling it 'a powerful weapon in our struggle against fascism.' Western critics, when the film became available after the war, acknowledged its technical merits while noting its overt propaganda elements. Modern film scholars recognize it as an important example of state-sponsored cinema that nonetheless contains genuine artistic merit, particularly in Pudovkin's directorial technique. The film is studied in film schools as an example of effective propaganda that maintains cinematic quality. Recent Russian critics have reevaluated the film as an important historical document that captures the spirit and ideology of its time, regardless of political considerations.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enormously popular with Soviet wartime audiences, who identified strongly with its depiction of ordinary soldiers defending their homeland. Soldiers at the front reportedly wept during screenings, recognizing their own experiences in the narrative. The film became mandatory viewing for military units and civilian workers alike. Post-war, it continued to be shown annually on Victory Day for decades. Among veterans, it was regarded as one of the most authentic portrayals of their wartime experience, despite its propagandistic elements. The film's emotional power resonated across generations of Soviet viewers, becoming part of the cultural memory of the Great Patriotic War.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize, First Class (1943)

- Order of the Red Banner of Labour awarded to director Vsevolod Pudovkin

- State Prize of the RSFSR (1943)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Battleship Potemkin (1925) - Pudovkin's montage techniques

- Alexander Nevsky (1938) - Eisenstein's historical epic style

- Chapaev (1934) - Soviet heroic military film tradition

- Lenin in October (1937) - Political propaganda techniques

- Classical Russian literature - Tolstoy's War and Peace

This Film Influenced

- The Cranes Are Flying (1957)

- Ballad of a Soldier (1959)

- Come and See (1985)

- The Ascent (1977)

- Stalingrad (1993)

- Enemy at the Gates (2001)

- Generation War (2013)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The original film elements are preserved in the Gosfilmofond of Russia, the state film archive. A restoration was completed in 2012 as part of a major project to preserve classic Soviet war films. The restored version premiered at the Moscow International Film Festival. Digital copies have been created for preservation purposes and are available through Russian film archives. Some original footage shot on location remains in excellent condition due to the high-quality Soviet film stock used during wartime.