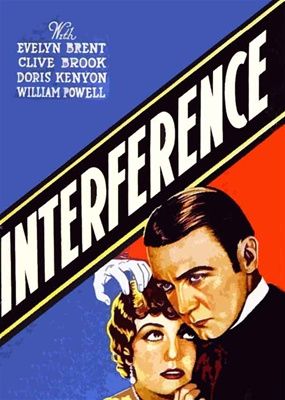

Interference

"Paramount's First All-Talking Picture"

Plot

In this early sound drama, Deborah Kane (Evelyn Brent) is a scheming woman who discovers that Sir John Marlay (Clive Brook), a prominent physician, is having an affair with her sister. Using this information as leverage, Deborah sets out to blackmail Faith Marley (Doris Kenyon), Sir John's virtuous wife. The plot thickens when Sir John's colleague Dr. David Trent (William Powell) becomes involved, attempting to protect the Marlay family from Deborah's malicious schemes. As the blackmail plot unfolds, it leads to murder accusations and a tense courtroom drama where the truth must finally emerge. The film explores themes of betrayal, honor, and redemption as the characters navigate the consequences of their actions in this tale of moral corruption and ultimate justice.

About the Production

Interference faced significant technical challenges as Paramount's first all-talking picture. The production required the installation of sound equipment throughout the studio, and actors had to adapt to the new demands of sound recording, including staying near microphones and modulating their voices appropriately. Director Roy Pomeroy, initially assigned as Paramount's 'technical wizard' for his expertise in sound technology, struggled with the dramatic aspects of directing and was reportedly replaced by Lothar Mendes during production. The film was shot using the Western Electric sound-on-film system, which Paramount had recently adopted.

Historical Background

Interference was produced during one of the most revolutionary periods in cinema history - the transition from silent to sound films. The Jazz Singer (1927) had just proven that talking pictures were commercially viable, and studios were racing to convert their productions to sound. By 1928, the film industry was in chaos as theaters scrambled to install sound equipment and studios retrained their personnel. Paramount, one of the major studios, invested heavily in sound technology and needed to demonstrate their commitment to the new medium. Interference served as this showcase, representing not just a single film but the studio's entire future in the sound era. The film's production coincided with the stock market boom of the late 1920s, just before the Great Depression would dramatically impact the film industry. This period also saw the end of many silent film careers and the rise of new stars who could successfully adapt to sound.

Why This Film Matters

As Paramount's first all-talking picture, Interference holds an important place in cinema history as a representative of the early sound era. The film demonstrated that dramatic stories with complex dialogue could successfully translate to the new medium, paving the way for more sophisticated sound films. It also showed that established dramatic actors like William Powell and Evelyn Brent could make the transition from silent to sound films, contrary to the fears of many studios about losing their star power. The film's commercial success helped accelerate the industry's complete conversion to sound within just two years. Interference represents the technical and artistic experimentation of this transitional period, where filmmakers were still learning how to effectively use sound to enhance storytelling rather than simply recording dialogue. The film also reflects contemporary anxieties about modern technology, with its title referencing radio interference, a cutting-edge concern of 1928.

Making Of

The production of Interference was fraught with the typical challenges of early sound filmmaking. The sound recording equipment was bulky and restrictive, forcing actors to remain relatively stationary during scenes. Microphones had to be hidden in props or set pieces, limiting camera movement. Director Roy Pomeroy, despite his technical expertise with sound equipment, struggled with directing actors in the new medium, reportedly giving too much attention to technical aspects while neglecting dramatic performances. This led to tensions on set and ultimately to his replacement by Lothar Mendes, who had more experience with dramatic direction. The cast had to undergo voice coaching to adapt their stage-trained projection to the more intimate requirements of microphone recording. Many scenes had to be reshot multiple times due to technical glitches, unwanted background noise, or actors' voices not recording properly. The film's success despite these challenges demonstrated that audiences were hungry for talking pictures and willing to overlook technical imperfections.

Visual Style

The cinematography in Interference reflects the constraints of early sound filmmaking. The camera work is notably static compared to the fluid camera movements common in late silent films, as the bulky sound recording equipment limited camera mobility. Director of Photography Henry W. Gerrard had to work within these limitations, using careful composition and lighting to maintain visual interest despite the restricted movement. The film uses relatively few close-ups, as early sound recording made it difficult to capture clear audio during tight shots. Lighting had to be carefully arranged to avoid noise from equipment, and many scenes were shot with flat, even illumination to ensure consistent sound quality. Despite these technical constraints, the film maintains a professional visual quality typical of Paramount productions, with well-designed sets and appropriate costumes that enhance the dramatic atmosphere. The visual style represents the transitional aesthetic of early talkies, where the visual sophistication of late silent films was temporarily compromised by the demands of sound recording.

Innovations

Interference represents several important technical achievements in early cinema history. As Paramount's first all-talking picture, it demonstrated the studio's successful implementation of the Western Electric sound-on-film system. The film showcased improved microphone placement techniques compared to earlier sound films, allowing for more natural actor movement while maintaining clear audio recording. The production team developed innovative methods for hiding microphones in set pieces and props, a technique that would become standard practice in sound filmmaking. The film also demonstrated advances in sound synchronization, with dialogue and effects properly aligned with the visual action. While not revolutionary in terms of technical innovation, Interference represented the refinement and practical application of sound technology that had been experimental just months earlier. The film's success proved that the technical challenges of sound filmmaking could be overcome to produce commercially viable entertainment, accelerating the industry's complete adoption of sound technology.

Music

As an early sound film, Interference featured a synchronized musical score and sound effects along with dialogue. The musical score was composed by John Leipold, Paramount's house composer, who provided appropriate background music to enhance the dramatic scenes. The film used the Western Electric sound-on-film system, which was considered state-of-the-art technology in 1928. The soundtrack included diegetic music (music within the story) as well as non-diegetic background score. Early sound films often struggled with music balance, and Interference was no exception, with some contemporary reviews noting that the music sometimes overwhelmed the dialogue. The film also featured sound effects that were considered innovative for the time, including door slams, telephone rings, and other environmental sounds that added realism to the scenes. The sound quality, while impressive for 1928, would be considered primitive by modern standards, with noticeable background hiss and limited frequency range. The soundtrack represents the early experimentation with film music that would eventually evolve into the sophisticated scoring techniques of the 1930s.

Famous Quotes

"A woman's reputation is like a delicate crystal - once shattered, it can never be whole again." - Deborah Kane

"In matters of honor, there can be no compromise." - Sir John Marlay

"The truth has a way of emerging, no matter how deeply buried." - Dr. David Trent

"Blackmail is a weapon that cuts both ways." - Deborah Kane

Memorable Scenes

- The tense blackmail scene where Deborah Kane confronts Faith Marley with the evidence of her husband's infidelity

- The courtroom sequence where Dr. Trent presents evidence that clears Sir John of murder charges

- The dramatic confrontation between Deborah and Sir John where the full extent of her scheme is revealed

- The final scene where justice is served and the characters face the consequences of their actions

Did You Know?

- This was Paramount Pictures' first all-talking feature film, marking a major milestone in the studio's transition to sound

- The film was based on a 1927 Broadway play of the same name by Harold Dearden and Roland Pertwee

- Roy Pomeroy, initially assigned to direct, was Paramount's designated 'technical wizard' for sound films but lacked directing experience, leading to his replacement

- Evelyn Brent was one of the few silent stars who successfully transitioned to talkies, largely due to her distinctive voice and acting style

- The film's success helped establish Paramount as a major player in the sound film revolution

- William Powell, who would later become famous for The Thin Man series, was still building his career as a leading man in 1928

- The movie was released just as the film industry was rapidly converting to sound, with many theaters still not equipped for sound projection

- Despite being an early talkie, the film contains surprisingly sophisticated dialogue and dramatic structure compared to other transitional films

- The original Broadway production had starred Leslie Howard and had a successful run of 167 performances

- The film's title refers to both radio interference (a contemporary concern) and the interference of characters in each other's lives

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics generally praised Interference as a successful early sound film, though many noted the technical limitations still apparent in the production. Variety reviewed it favorably, stating that 'Paramount has made a creditable job of its first all-talking picture' and particularly praised Evelyn Brent's performance. The New York Times noted that while the film had 'some of the stiffness common to early talkies,' it was 'nevertheless an engaging drama with good performances.' Modern critics view the film as an interesting artifact of the early sound era, with its historical significance often outweighing its artistic merits. Film historians appreciate it as an example of how quickly filmmakers adapted to the new technology, creating relatively sophisticated dialogue and dramatic structure despite the technical constraints. The film is generally regarded as better than many of its contemporaries from the same transitional period.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1928 were fascinated by Interference primarily because it was a talking picture, a novelty that still drew crowds despite the technical imperfections. The film performed respectably at the box office, particularly in urban areas where theaters had been equipped for sound. Moviegoers were reportedly impressed by the clarity of the dialogue and the naturalistic performances compared to the exaggerated acting style common in silent films. The dramatic storyline, with elements of blackmail and romance, appealed to mainstream audiences of the era. However, some viewers complained about the sound quality and the static nature of the staging, which resulted from the technical limitations of early sound recording. Despite these issues, the film's success demonstrated that audiences had fully embraced sound cinema and were willing to pay premium prices for talking pictures, accelerating the industry's complete conversion to sound within the next year.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards recorded for this film

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Broadway play Interference (1927) by Harold Dearden and Roland Pertwee

- The Jazz Singer (1927) - as an early sound film influence

- German expressionist cinema - in its dramatic lighting and composition

- Stage melodrama - in its heightened emotional content

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent early Paramount talkies

- The Letter (1929) - another drama of adultery and consequences

- The Unholy Night (1929) - early sound drama with similar themes

- Later films about blackmail and scandal

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Interference is believed to be a lost film. Like many early sound films, particularly those from the transitional period of 1928-1929, no complete copies are known to exist in major film archives. The film's disappearance is particularly unfortunate given its historical significance as Paramount's first all-talking picture. Early sound films faced preservation challenges due to the deterioration of nitrate film stock and the complexity of preserving synchronized sound tracks. Some sources suggest that fragments or audio tracks may exist in private collections, but a complete version has not been located. The film represents one of the significant losses from early cinema history, though still photographs and contemporary reviews provide documentation of its existence and content.