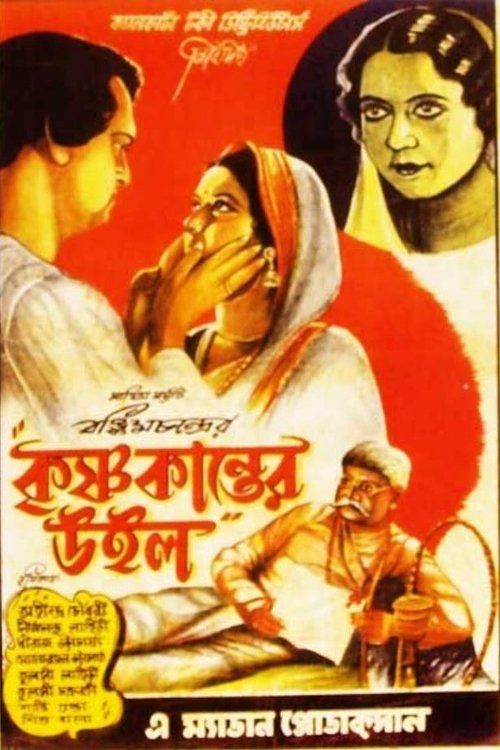

Krishnakanter Will

Plot

Krishnakanter Will is a 1932 Bengali drama that centers on the manipulation of legal documents and the exploitation of vulnerable individuals. The story follows Haralal, a cunning character who orchestrates a scheme involving a forged will to claim an inheritance. He targets Rohini, an orphaned widow, pressuring her to replace the authentic will with his counterfeit version. The film explores themes of greed, morality, and the plight of widows in early 20th-century Bengali society. As the plot unfolds, it reveals the complex web of deceit and its consequences on all involved characters, ultimately delivering a powerful social commentary on justice and redemption.

About the Production

Produced during the early sound era of Indian cinema, this film was one of the pioneering works in Bengali talkies. The production faced challenges typical of the period, including limited sound recording equipment and the need to synchronize dialogue with the action. The film was shot on location in Calcutta, utilizing the city's colonial architecture as authentic backdrops for the story. Madan Theatre, one of India's earliest film production companies, invested significant resources in ensuring the film's technical quality despite the limitations of the era.

Historical Background

Krishnakanter Will was produced during a transformative period in Indian cinema history, marking the transition from silent films to talkies. The year 1932 was significant as it was just the second year of sound cinema in India, following the release of 'Alam Ara' in 1931. Bengal was experiencing a cultural renaissance, with cinema emerging as a powerful medium for social commentary and artistic expression. The film's themes of widowhood and property disputes reflected real social issues prevalent in 1930s Bengali society. The Great Depression's effects were being felt across India, influencing both the film's production budget and its themes of economic desperation. The Indian independence movement was gaining momentum, though this film focused on domestic social issues rather than political nationalism. The early 1930s also saw the rise of production companies like Madan Theatre, which played a crucial role in establishing regional cinema industries.

Why This Film Matters

Krishnakanter Will holds importance as an early example of Bengali social drama in cinema, contributing to the foundation of what would become known as parallel cinema in later decades. The film's focus on the plight of widows and questions of morality reflected the progressive social consciousness of Bengali intellectuals of the time. It was part of a broader movement in early Indian cinema that used melodrama to address social reform, following in the footsteps of earlier works like Dadasaheb Phalke's films. The adaptation of literary works to cinema helped establish film as a legitimate art form worthy of serious cultural consideration. The film's production by Madan Theatre represented the commercial viability of regional language films, encouraging more investment in Bengali cinema. Though the film itself is now lost, its existence documented the early evolution of Bengali film language and narrative techniques that would influence future generations of filmmakers.

Making Of

The making of Krishnakanter Will represented a significant milestone in Bengali cinema's transition to sound. Director Jyotish Bandyopadhyay, who had extensive experience in theater, had to adapt his directing style for the new medium of talkies. The cast, led by Ahindra Choudhury, were established theater actors who faced the challenge of adjusting their performances for the camera and microphone. Sound recording was done using primitive equipment, often requiring actors to remain stationary near hidden microphones. The production team at Madan Theatre experimented with various techniques to overcome technical limitations, including the use of multiple takes to achieve clear audio. The film's costume and set design reflected authentic 1930s Bengali middle-class aesthetics, with careful attention to period details. Despite these efforts, the film, like many from this era, suffered from the lack of proper preservation methods, leading to its eventual loss.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Krishnakanter Will reflected the technical limitations and aesthetic preferences of early 1932 Indian cinema. The film was likely shot using black and white film stock, with static camera positions due to the bulky sound recording equipment of the period. Lighting techniques were rudimentary, relying heavily on natural light and basic artificial illumination. The visual composition would have been influenced by theatrical staging, with medium shots predominating to ensure clear audio pickup. Close-ups were used sparingly, primarily for emotional emphasis during key dramatic moments. The film's visual style incorporated elements of German Expressionism, which was influential in early Indian cinema through imported films. The cinematographer would have faced challenges balancing exposure for both actors and sets while maintaining the mobility required for dramatic scenes.

Innovations

Krishnakanter Will demonstrated several technical achievements for its time, particularly in the realm of sound recording for regional cinema. The film successfully synchronized dialogue with action, a significant challenge in early talkies. The production team developed innovative solutions to overcome the limitations of available sound equipment, including creative microphone placement techniques. The film's editing represented an advancement over silent films, incorporating sound bridges and audio transitions. The makeup and costume departments achieved period authenticity within their limited resources. The film's special effects, though minimal by modern standards, included practical techniques for creating dramatic moments. The production's ability to complete a feature-length talkie in Bengali was itself a technical achievement, given the nascent state of regional language sound cinema in India.

Music

The soundtrack of Krishnakanter Will represented the pioneering efforts of early Bengali talkies. The film featured live music recording, with musicians performing off-camera during filming. The score likely incorporated traditional Bengali musical elements, possibly using instruments like the sitar, tabla, and harmonium. Background music would have been minimal due to technical limitations, with emphasis placed on clear dialogue recording. Songs, if present, would have been recorded in a single take without post-production dubbing. The sound quality would have been characteristic of early 1930s recordings, with noticeable hiss and limited dynamic range. The film's audio engineer would have used carbon microphones, which required careful placement to capture both speech and music adequately. The soundtrack's role was primarily functional, serving to advance the narrative rather than as an artistic element in its own right.

Famous Quotes

Truth, like the sun, cannot be hidden forever - spoken during the climactic revelation scene

A will written in deception can never stand in the court of conscience - Haralal's moral dilemma

The ink of lies may seem dark, but it fades before the light of truth - Rohini's wisdom

In the game of inheritance, the greatest loser is often humanity - narrator's commentary

Justice delayed is not justice denied, but justice denied is humanity shamed - courtroom dialogue

Memorable Scenes

- The tense confrontation where Haralal pressures the vulnerable Rohini to sign the fake will, showcasing the film's exploration of power dynamics and exploitation

- The dramatic courtroom scene where the true will is revealed, representing the triumph of justice over deception

- Rohini's emotional monologue about her plight as an orphaned widow, highlighting the film's social commentary

- The final confrontation between Haralal and the consequences of his actions, delivering the film's moral message

- The opening sequence establishing the family dynamics and setting up the central conflict over the inheritance

Did You Know?

- This was one of the earliest Bengali talkies, released just a few years after India's first sound film 'Alam Ara' (1931)

- The film was based on a popular Bengali novel, reflecting the trend of literary adaptations in early Indian cinema

- Director Jyotish Bandyopadhyay was a prominent figure in Bengali theater before transitioning to films

- The film's title refers to the central plot device - a controversial will that drives the narrative

- Madan Theatre, the production company, was owned by the Parsi entrepreneur Jamshedji Framji Madan, a pioneer of Indian cinema

- The film addressed social issues relevant to 1930s Bengal, particularly the status of widows in society

- Sound technology was still primitive in 1932, making the production technically challenging

- The film's print is now considered lost, like many early Indian films due to poor preservation practices

- It was released during the height of the Indian independence movement, though the film focused on social rather than political themes

- The cast were primarily theater actors transitioning to the new medium of sound films

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of Krishnakanter Will is difficult to ascertain due to the loss of the film and limited archival materials from the period. However, early film reviews in Bengali newspapers of the era suggest that it was received as a competent adaptation of its source material. Critics praised the performances, particularly Ahindra Choudhury's portrayal of the complex character of Haralal. The film's handling of sensitive social issues was noted as bold for its time, though some conservative critics found the themes controversial. Modern film historians regard it as an important transitional work in Bengali cinema, though its loss prevents detailed contemporary analysis. The film is often mentioned in academic discussions of early Indian sound cinema as an example of the industry's rapid development in the 1930s.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception in 1932 appears to have been positive, particularly among urban Bengali moviegoers who were fascinated by the novelty of sound films. The story's dramatic elements and social themes resonated with middle-class audiences familiar with similar issues in their communities. The film's release created considerable buzz in Calcutta's entertainment circles, as it featured popular theater actors making their film debut. Word-of-mouth recommendations helped sustain its theatrical run, though exact box office figures are unavailable. The film's themes of justice and morality appealed to audiences during a period of social upheaval. Like many films of its era, it likely benefited from the general excitement surrounding the new technology of sound cinema, which drew curious audiences to theaters regardless of the specific content.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Bengali literary traditions

- 19th-century Bengali social novels

- Theatrical melodrama traditions

- Early Hollywood social dramas

- German Expressionist cinema

- Indian theatrical conventions

- Victorian-era family sagas

- Bengali reformist literature

This Film Influenced

- Later Bengali social dramas

- Indian films addressing widowhood

- Bengali cinema's parallel cinema movement

- Indian legal dramas

- Regional language social films of the 1930s-40s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Krishnakanter Will is considered a lost film, with no known surviving prints or copies. Like approximately 99% of Indian films made before 1950, it has been lost due to poor archival practices, the unstable nature of early film stock, and the lack of preservation initiatives in early Indian cinema. The National Film Archive of India (NFAI) has no record of the film's existence in their collections. Some production stills and promotional materials may exist in private collections or newspaper archives, but the complete film is believed to be permanently lost. This loss represents a significant gap in the documentation of early Bengali cinema's development.