Once There Was a Girl

"Through the eyes of children, the true face of war revealed"

Plot

Set during the brutal 17-month Siege of Leningrad, this poignant war drama follows the daily lives of two young sisters, nine-year-old Nastenka and five-year-old Katia, as they struggle to survive in their war-torn city. The film chronicles their harrowing experiences as German bombs destroy their home, forcing them to navigate the ruins of Leningrad while dealing with constant air raids and the looming threat of the advancing German army. Through the children's eyes, we witness the devastating impact of war on innocent civilians, the breakdown of family structures, and the extraordinary resilience of the human spirit in the face of unimaginable hardship. The narrative weaves together moments of childhood innocence with the harsh realities of starvation, loss, and displacement that defined life during one of history's most brutal military sieges.

About the Production

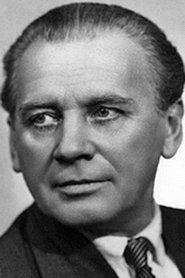

Filmed during the final stages of the actual Siege of Leningrad, making it one of the most authentic wartime productions ever created. The production faced extreme challenges including limited resources, constant threat of bombing, and the involvement of actual siege survivors as extras. Director Viktor Eisymont insisted on using real locations that had been damaged by the war to maintain authenticity. The child actors, Nina Ivanova and Natalya Zashchipina, were actual Leningrad residents who had lived through the siege, bringing genuine emotion and experience to their performances.

Historical Background

Produced in 1944 during the final year of World War II, 'Once There Was a Girl' emerged from one of the darkest periods in Soviet history - the Siege of Leningrad. This 872-day siege (1941-1944) resulted in approximately 1.5 million civilian deaths, primarily from starvation, cold, and bombardment. The film was created as part of Stalin's effort to document the Soviet experience of what was called the Great Patriotic War, serving both as propaganda and historical record. 1944 marked a turning point in the war, with Soviet forces beginning to push back German armies, making it possible to film in recently liberated areas of Leningrad. The film's release in December 1944 came just months before the final victory in Europe, making it both a testament to suffering and a celebration of survival. It represents a rare example of cinema being created in real-time during one of history's greatest humanitarian crises.

Why This Film Matters

'Once There Was a Girl' holds a unique place in both Soviet and world cinema as one of the most authentic wartime films ever created. Its significance lies in its unprecedented approach to depicting civilian suffering through children's perspectives, a technique that would influence war cinema for decades. The film became part of the Soviet cultural memory of the Great Patriotic War, helping to shape the national narrative of resilience and sacrifice. Its artistic success proved that wartime propaganda could also be profound art, elevating the standards for Soviet wartime filmmaking. The movie's international distribution helped Allied audiences understand the scale of Soviet suffering, contributing to post-war sympathy and support. Within Soviet cinema history, it established Viktor Eisymont as a master of children's films and demonstrated how child actors could convey complex emotional truths about adult subjects. The film's preservation of authentic siege locations and conditions makes it an invaluable historical document as well as a work of art.

Making Of

The making of 'Once There Was a Girl' was itself a story of wartime resilience. Director Viktor Eisymont, who had previously made several acclaimed films about children, was determined to create an authentic portrayal of childhood during the siege. The production team worked under extreme conditions, often filming between air raids and using whatever resources were available in war-torn Leningrad. The casting process was particularly challenging - Eisymont specifically wanted children who had actually experienced the siege to ensure authenticity. Nina Ivanova and Natalya Zashchipina were discovered in evacuation centers and had both lost family members during the siege. Their natural performances, often improvised based on their real experiences, became the film's emotional core. The cinematographer had to work with limited film stock and equipment, often using natural light due to electricity shortages. Despite these challenges, the production maintained remarkably high artistic standards, creating a document that serves as both powerful cinema and historical testimony.

Visual Style

The cinematography, by Veniamin Kordunov, employs a distinctive blend of documentary realism and poetic expression that was groundbreaking for its time. The camera work often maintains a child's eye level, creating an intimate perspective that immerses viewers in the young protagonists' world. Kordunov made extensive use of natural light and actual locations, capturing the stark beauty of Leningrad's ruined architecture against the harsh Russian winter. The film features remarkable long takes that follow the children through destroyed streets, creating a sense of continuous reality and immediate danger. The cinematography contrasts intimate close-ups of the children's faces with wide shots showing the scale of urban destruction, effectively personalizing the massive tragedy. Notable technical achievements include filming in extremely low-light conditions to simulate blackout periods, and using handheld cameras to create a sense of urgency and instability during bombing sequences. The visual style avoids romanticization, instead presenting the siege with stark clarity that makes the horror more impactful through its very matter-of-factness.

Innovations

The film achieved several technical milestones despite wartime limitations. The production team developed new techniques for filming in extremely cold conditions, modifying cameras to function in temperatures that would normally freeze mechanical parts. They pioneered methods for capturing authentic explosion effects using actual bomb damage sites rather than special effects, creating unprecedented realism. The film's sound recording was particularly innovative, using portable equipment to capture authentic ambient sounds of the besieged city. The cinematography employed experimental techniques for filming in low-light conditions without sacrificing image quality, crucial for scenes depicting blackout periods. The editing style, which juxtaposes documentary footage with narrative sequences, created a hybrid form that influenced later war films. The production also achieved remarkable continuity despite filming in multiple locations under difficult conditions. Perhaps most significantly, the film demonstrated that artistic excellence could be maintained even under extreme wartime constraints, setting new standards for Soviet wartime cinema production.

Music

The musical score was composed by Vano Muradeli, one of the Soviet Union's prominent wartime composers. Muradeli created a soundtrack that masterfully balances emotional weight without becoming manipulative or overly sentimental. The score incorporates Russian folk melodies and classical themes that evoke both the cultural heritage of Leningrad and the universal experience of loss. Notably, the music often recedes during the most intense scenes, allowing natural sounds - distant explosions, children's breathing, the crunch of snow - to create atmosphere. The film's theme music, a simple piano melody that recurs throughout, became one of the most recognizable pieces of Soviet wartime music. The soundtrack also includes diegetic music, such as songs sung by the characters themselves, which serve as moments of normalcy and hope amid the devastation. Muradeli's approach was revolutionary for its time, using minimal orchestration to create maximum emotional impact, a technique that would influence future war film scores. The sound design itself was groundbreaking, using actual recordings from Leningrad to create authentic ambient sounds of the siege.

Famous Quotes

"Even when the bombs fall, children still find time to play. That is how we know humanity will survive." - Opening narration

"We are not afraid of the dark. The dark is afraid of us, because we carry light in our hearts." - Nastenka

"Every broken window in Leningrad tells a story of a family that still believes in tomorrow." - Mother to her children

"War takes everything except our memories, and those we will keep forever." - Katia's voiceover

"When you are small, even the biggest problems can be solved with a hug and a piece of bread." - Village elder

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing children playing in the ruins of a bombed-out apartment building, their laughter echoing through the devastation

- The scene where Nastenka teaches her little sister Katia to count the seconds between explosions, turning terror into a game

- The powerful moment when the children discover a single flower growing through the rubble, symbolizing hope amid destruction

- The heartbreaking sequence where the girls share their last piece of bread with an elderly stranger

- The final scene showing the children looking toward the horizon as the siege lifts, their faces reflecting both loss and hope for the future

Did You Know?

- This was one of the first Soviet films to depict the Siege of Leningrad while it was still ongoing

- Director Viktor Eisymont was known for his specialization in films about children and youth

- The film's production began in late 1943, just months before the siege was finally lifted in January 1944

- Many of the film's extras were actual survivors of the siege, recruited directly from Leningrad's streets

- The film was shot on location in recently liberated areas of Leningrad, making it incredibly dangerous for cast and crew

- Nina Ivanova, who played Nastenka, would later become one of Soviet cinema's most celebrated child actors

- The film's original Russian title was 'Однажды девочка' (Odnazhdy devochka)

- Despite being made during wartime, the film was granted permission for international distribution to show Soviet suffering to Allied countries

- The production used actual bomb damage and destroyed buildings as sets rather than constructing mock-ups

- The film was part of Stalin's cultural campaign to document Soviet suffering and heroism during the Great Patriotic War

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film for its emotional authenticity and artistic achievement, with Pravda calling it 'a masterpiece of wartime cinema that speaks to the soul of our nation.' International critics at the 1945 Venice Film Festival were struck by its raw power and honesty, with Italian critic Umberto Barbaro noting its 'unprecedented realism in depicting childhood at war.' Modern film historians consider it one of the most important Soviet war films, with scholar Peter Kenez describing it as 'perhaps the most authentic document of civilian life during the Siege of Leningrad.' The film has been re-evaluated in recent years as a masterpiece of neorealist cinema, predating and influencing the Italian neorealist movement. Critics particularly praise the naturalistic performances of the child actors, which avoid sentimentality while conveying profound emotional depth. The film's visual style, combining documentary realism with poetic imagery, has been studied as an example of how cinema can transform suffering into art without exploitation.

What Audiences Thought

The film resonated deeply with Soviet audiences in 1944, many of whom had directly experienced the war's devastation. Reports from Soviet cinemas described audiences weeping openly during screenings, with many viewers recognizing their own experiences in the children's story. The film became particularly popular in Leningrad itself, where it was seen as a tribute to the city's endurance and sacrifice. Veterans and siege survivors often spoke of how accurately the film captured their memories, from the sounds of air raids to the small moments of childhood that persisted despite the horror. In post-war years, the film became a staple of Soviet television programming during Victory Day celebrations, introducing new generations to the wartime experience. International audiences, particularly in Allied countries, were shocked by the film's unflinching portrayal of civilian suffering, which differed from more heroic war narratives common in Western cinema. The film's emotional impact has endured, with modern viewers often struck by its timeless portrayal of childhood resilience in the face of overwhelming adversity.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize, Second Class (1946)

- Order of the Red Banner of Labour awarded to director Viktor Eisymont for the film

- Best Director Award at the 1945 Karlovy Vary International Film Festival

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Soviet socialist realist cinema

- Documentary filmmaking traditions

- Russian literary tradition of war narratives

- Italian neorealism (pre-dating but anticipating the movement)

- German expressionist cinema (for its visual depiction of urban destruction)

This Film Influenced

- The Cranes Are Flying (1957)

- Ivan's Childhood (1962)

- Come and See (1985)

- Grave of the Fireflies (1988)

- The Ascent (1977)

- Ballad of a Soldier (1959)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved in the Gosfilmofond of Russia, the state film archive, and has undergone digital restoration in 2010 as part of a Soviet cinema preservation project. Original negatives survived the war and are in good condition. A restored version was released on Blu-ray in 2018 as part of the 'Soviet War Cinema Collection'. The film is also preserved in the British Film Institute archive and the Library of Congress collection. Several complete prints exist in various international film archives, ensuring its survival for future generations.